THE King James Bible weighs in at 783,137 words. The diary of Samuel Pepys, housed at Magdalene College, Cambridge, is just over one million words in length. The 180 bound notebooks that make up the diary of A. C. Benson (1862-1925), Eton beak and Master of Magdalene, contain well over four million words. To select less than a 12fth of the whole Benson diary, to annotate each entry, and to provide an introduction of 74 pages is a labour of love, brilliantly executed by two senior historians at the college, of which Hyam is an Archivist Emeritus. Their selection is an important historical document.

In analysing Arthur and his siblings, the children of Archbishop Edward White Benson, the editors have to grapple with A Very Queer Family Indeed, the subject of Simon Goldhill’s book on the Bensons’ “graphomania” (Books, 25 November 2016). (The Archbishop was the only heterosexual in the family.) They directly address the rather sad story of Arthur’s yearnings for attractive young men and succeed in presenting a balanced picture of the most successful housemaster at Eton in the late Victorian period, unofficial poet laureate to the royal family and editor of Queen Victoria’s letters, bestselling popular philosopher and witty public speaker, and master of a small Cambridge college, every stone of which he came to love.

Benson knew everybody who was anybody, moving among the leading literary, religious, and political circles of his day, attending Gladstone’s funeral and the coronation of Edward VII, dining with Queen Victoria at Windsor and his eminent chums at the Athenæum, hobnobbing with Prime Ministers and foreign statesmen, comparing notes with Swinburne, Hardy, Housman, Yeats, Bridges, Henry James, Wells, Chesterton, Belloc, E. M. Forster, and George Bernard Shaw.

The editors argue, however, that the diary’s unique flavour derives not from its accounts of celebrities, but, rather, from the “opinionated, sardonic and irreverent personality of the diarist”. Having spent most mornings answering thirty or forty letters, Benson would write up a diary that is entertaining to read because of its “sharp observation, humour, malice and saltiness”.

The diary will be of particular interest to students of depression, sometimes accompanied by paranoid delusions, which completely disabled Benson for months, even years on end, and led to consultations with ten specialists recommended by the family doctor. Sceptically, he tried hypnotherapy, spa water, and colonic irrigation. Only time rescued him. Memories of a mysterious “great misfortune” as a classics Scholar at King’s in 1882 haunted him, as did the family prayers of his boyhood.

In private, the Archbishop’s son described Christianity as “a very mixed affair”. The Apostles were “very inferior people” in his view. Christianity as understood in his own day would surely be superseded by a new “much simpler, much larger” religion, which would teach people to “live finely in themselves” instead of “propping up & comforting the weak”.

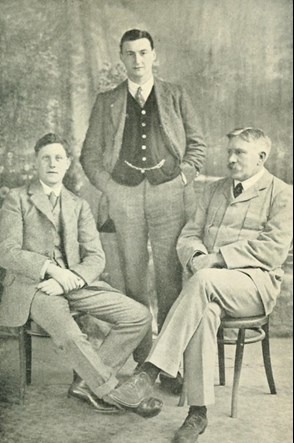

AlamyBenson with younger friends, Frank Walker (left) and Geoffrey Winterbotham, on holiday in Burford, April 1911. Winterbotham was described in the diaries as “moderately” able, but “. extraordinarily sweet-tempered and affectionate”

AlamyBenson with younger friends, Frank Walker (left) and Geoffrey Winterbotham, on holiday in Burford, April 1911. Winterbotham was described in the diaries as “moderately” able, but “. extraordinarily sweet-tempered and affectionate”

Science and historical criticism had undermined Christian claims to historicity. The Bible was not “a relation of the dealings of God with men”, but “only a relation of the imaginations of men about God, interspersed with many romantic fables”. Kingsley was “nobler, far more manly, reasonable, impetuous, human” than Keble. Manning was “deeply interesting”, “a complete egotist & self-deceiver”. “Poor Farrar!” he exclaims, “the obviousness of everything said & thought” in Julian Home. Bishop Westcott was “an odd mixture of genius & little fads”. Henry Scott Holland was “a really charming person, so quickly sympathetic”.

Arthur’s father was succeeded at Canterbury by Frederick Temple. What people didn’t know was that Temple “never answered letters, played patience half the day, & read schoolboy stories in bed”.

The more outrageous comments in the diary often reflect the prejudices of a superfine English elite, as when he announces in 1897 that the Welsh are like goats: “They are surly, stupid & conceited.”

Sometimes wayward in his generalisations, he is always a perceptive observer of individuals. Lord Rayleigh is “as nice as ever”, he records in 1903: “He subsides in a chair, or crosses one leg over another in an attitude which means nervous tension — or holds out his white shapely pointed fingers in a spasmodic way — but he is excellent company — so full of humour, & I enjoy his wrinkled eyes & giggling laugh, which goes on so long & takes you so into his confidence.”

What Benson values in a talker is “brevity, humour, suggestiveness, quickness”. All that is in his diaries, too.

Dr Wheeler read English at Magdalene in the late 1960s. His latest book is William Ewart Gladstone: The heart and soul of a statesman (OUP) (Books, 11 April).

The Benson Diary: I: 1885-1906; II: 1907-1925

Eamon Duffy and Ronald Hyam, editors

Pallas Athene £60

(978-1-84368-277-6)

Church House Bookshop £54