Job 19.23-27a; Psalm 17.1-9 (or 17.1-8); 2 Thessalonians 2.1-5,13-end; Luke 20.27-38

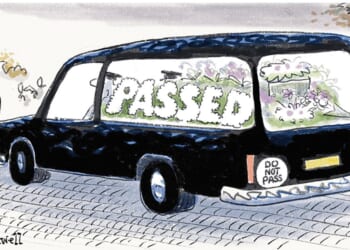

SOME questions — rhetorical questions — do not require answers. Others appear to ask one thing, but actually ask something else. A famous Civil War painting (dating to 1878) by William Frederick Yeames has a question for its title: And When Did You Last See Your Father? A Roundhead interrogator is effectively asking a Cavalier’s young son, “Where can I find your father, so that I can arrest him?”

Another question type is the performative, designed to improve the questioner’s image while discrediting someone else (these are common as rats in university seminars). Here, some Sadducees set Jesus a test case: a woman with seven husbands. They ask, “In the resurrection, whose wife will the woman be?”, to expose his unsound opinions. It was probably a stock question for opponents. In part, this was class war: one Jewish writer remarks, “The Sadducees were rich but unpopular; the Pharisees had mass support.”

When street evangelists ask, “Have you met Jesus as your personal friend and saviour?”, they must listen carefully to any reply, because it will shape the conversation that follows: they aim to persuade. The Sadducees, though, are not listening. They want to expose Jesus as a Pharisee opponent. They do not expect to learn anything that will modify their own views. They are not open to persuasion.

Jesus’s teaching here is not drawn from the Pharisees, who, as opponents of the Sadducees, did believe in a resurrection; nor is it founded on any sacred writings. It emerges purely from his own self. In verses 34-36, he outlines his expectations for the idea of the general resurrection of the dead. Opposing that widespread belief was fundamental to the identity of a Sadducee: they held strictly to what was written in the Law, and nothing more (unlike the Pharisees, Luke 11.42).

This general resurrection is not directly related to Christian faith as we recognise it — Jesus, the first-fruits of new-covenant resurrection, after whose example those who believe in him will constitute the harvest. Sometimes, the Gospel-writers expose their foreknowledge of events that, within the Gospel story, remain in the unknown future, as when Jesus tells his disciples to “take up their cross”, at a time when he has not yet undergone crucifixion (Luke 9.23; Matthew 16.24; Mark 8.34). But here there is no predictive reference to the Lord’s resurrection.

In verse 36, he summarises with three points: those who are worthy of a place in the age to come, and worthy of resurrection (1) cannot die any more, (2) are like angels, and (3) are children of God, which means being “children of the resurrection”. Thus, Jesus teaches the Sadducees that they have misunderstood what belief in life after this life is all about. We must remember that they have asked him this precisely because of their conviction that it is silly to imagine the life of the world to come being just like this one, in which men and women are born, and marry, and die.

Jesus almost agrees with them. His answer to their pseudo-question flips their negative conviction (“there is no resurrection”) into a positive: they are right, he says, that the world to come will not resemble this one. In that new way of being (which Christians recognise as the Kingdom of God), there will be no more time-bound human institutions such as marriage, and no more time-driven human experiences, such as death.

One lesson for us to learn from today’s Gospel could be that Jesus does not say to the Sadducees: “Your interpretation of God’s purposes is wrong: you have misunderstood resurrection completely.” So often in our disagreements (which are natural and unavoidable in human relationships and our common life), we protect our own beliefs by condemning other people’s. Jesus shows a more excellent way: to say what we think is right, refer to the Bible when relevant (verse 37), and let truth speak for itself. Jesus’s truth convinces some listeners (Luke tells us that they are “scribes”): “Teacher, you have spoken well” (just after the lection, 20.39).

Perhaps the Sadducees and Pharisees hated each other so much because the difference between them was so small. So, back to that famous painting. Disagreements can make good people do bad things (Luke 21.16). I hope that God would forgive the questioner his interrogation, or forgive the boy, if he lied to protect his father. On Remembrance Sunday, as — looking forward to Advent — on Judgement Day, there is “a wideness in God’s mercy”.