A RURAL benefice of 14 churches designated as a “mission hub” in the diocese of Salisbury as part of a new multi-million-pound programme is not expecting to “massively grow” its Sunday congregations, one of its leaders said last week. Instead, the focus will be on “working better alongside people where they are” and demonstrating that the rural church is “still growing, thriving, and sustainable”.

Canon Jo Neary, a pioneer priest who has been a Team Vicar in the Beaminster Area Team Ministry for 13 years, said that the vision was “much less about trying to get people to come to us, and more about us meeting people where they are. . . That won’t necessarily mean they come to church on a Sunday: it might be they worship in a different place at a different time.”

Her comments come in the wake of evaluations of projects in rural areas funded by the national Strategic Development Fund (SDF) and Strategic Mission and Ministry Investment Board (SMMIB) which warn against setting unrealistic goals. An evaluation of the “Rural Hope” project in the diocese, which received a grant of £1.27 million in 2017, warned that SDF numerical targets “do not easily translate to parish level where relational growth and organic organic growth is so important”.

What’s in our Hands? a rural mission-learning review for the Church House Vision and Strategy Team, carried out by the Revd Dr Richard Tiplady for Brendan Research, and exploring ten projects, concluded that a “key learning” could be found in a Winchester report: “Success in rural contexts is subtle. Growth in attendance is modest at best or is about maintaining numbers.” In rural areas, “the journey to faith is a long slow one. Large numbers of contacts rarely translate into significant increases at existing worship services.” Demographics in deep rural areas meant that “maintaining Sunday attendance numbers is growth in disguise.”

The mission-hubs programme in Salisbury will receive the majority of the £5.1- million SMMIB award announced in June. Thirteen “missionally healthy” parishes have been designated as hubs, expected to “establish creative partnerships with churches around them to offer resource, people and expertise”. Of the 13, almost all are Evangelical single-parish benefices. Six are in market towns, alongside parishes in Poole, Weymouth, and Salisbury.

The Chote review of the SDF programme (News, 11 March 2022) highlighted an “urgent need to identify sustainable models of rural ministry” across the Church. Ninety per cent of parishes in Salisbury are rural, most of them multi-parish benefices. Half of the population live in seven per cent of the parishes.

Last month, Canon Jonathan Triffitt, the diocesan director of mission and ministry, spoke of the hope that, “if we can get it right for our largest one [Beaminster], what might it look like in other multi-parish benefices? . . .

“Ultimately, it’s deeply relational. It’s not just about how we nurture a healthy missional church in a rural context, but what does it look like to invest in healthy rural communities, of which the church is part?”

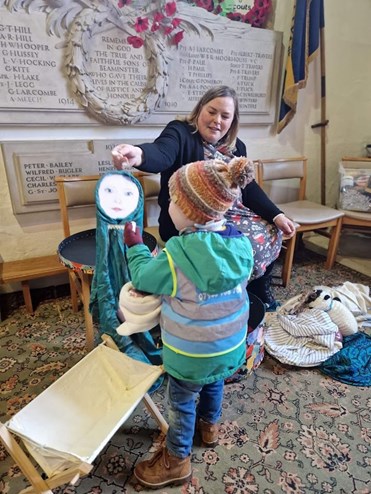

JO NEARYCanon Neary at the nativity festival in St Mary’s, Beaminster, in 2023, exploring the story with pre-school children

JO NEARYCanon Neary at the nativity festival in St Mary’s, Beaminster, in 2023, exploring the story with pre-school children

The expectations were that the work would take longer, he said. “It isn’t just about pumping resources in around paid roles. But it is exploring ‘How does this rural community enable effective discipleship? How do we raise leaders when we have a 45 per cent vacancy rate for churchwardens?’” What might “new patterns of leadership” look like, giving “permission to do different things in different ways”?

Most of the 600 buildings in the diocese of Salisbury were Grade I listed, and an “increasing number” were “vulnerable to closure in the coming years because of the drop in worshipping communities”, he said. “For us, just closing the building is not the answer. How do we create a mechanism where buildings can be entrusted into the care of others to allow local leaders to engage in their community?”

There needed to be “theological accompaniment” to this work, he suggested. “I am more interested, to be honest, in the theological learning. What is the Holy Spirit saying? What are we discovering about who God is calling us to be in these particular contexts?”

In Beaminster, Canon Neary, who is a tutor in rural ministry and mission at Sarum College in the diocese, serves along with one full-time stipendiary priest, the Team Rector, Canon David Baldwin. The parish church of Beaminster, a town of 3000, has a service once a week; the other 13 have a service every other week. When everyone is in attendance, about 250 worship every Sunday. The village church congregations number between ten and 20.

The “mixed ecology” was also under way through a messy church (55 attending), a community outreach-café, and online church, Canon Neary said. The many occasional offices were taken “very seriously”, and collective worship was held in the four primary schools every week. The aims of the mission hub included encouraging vocations, working with children and young people, and sharing “expertise and experience” with other rural teams. Another was greater collaborative working, “to try to think about how to sustain the buildings, and governance . . .

“We don’t really expect to massively grow our Sunday congregations, but we think that that’s OK because we want to really invest in what it looks like to be a team of churches working across the whole community. . . Our primary goal is to make Jesus known everywhere.” As a tutor in rural ministry, she sought to convey the recognition that “there is life and joy and innovation here.”

Among the findings of the Rural Hope evaluation was the challenge of communicating the programme across the diocese and gaining “buy-in”: almost two-thirds of those on the rural mailing list had very little awareness of its aims.

The Team Rector in the Canford Magna Ministry, which includes the Lantern Church, Merley, in Wimborne (not a mission hub), the Revd Mike Tufnell, said that he was in favour of the mission hubs, but there were “plenty of questions, and some concerns . . . mostly from smaller churches asking where their extra support is. It would be fair to say there was some scepticism that the injection of resources will really ‘trickle down’ to them or meet their felt ministry needs.”

He said: “Where there is the will to resource others, partnering relationally, with generosity, this model can work well — we have some experience of that here — but there is naturally the risk that it boosts existing ministry at larger churches for the next few years, but without necessarily partnering effectively, ‘so that all may flourish and grow’. I’m confident the diocesan leadership are well aware of those challenges and are committed to supporting every parish, not just these ‘hubs’. I’ll be praying for the fruitfulness of the vision.”

The Rector of the Wellsprings Benefice, the Revd Gerry Lynch, said that he had been “nonplussed when I saw how monochrome the churches are, but I appreciate the diocese has to jump through hoops set by national Church. I don’t get angry or upset, I just ignore as much of it as I can.” He had received no information about how other parishes would benefit from the project, he said.

Last month, Canon Triffitt acknowledged that resentment towards those churches in receipt of investment was “always a risk”. There was an expectation that the leaders of the hubs would be “actively engaging in conversations at the earliest possible moment. . . This isn’t about any one church stepping in and saying ‘We’ve got all the answers.’” They had made a commitment to investing £7 million of their own resources to ensure the sustainability of the work.

The Brendan Research review of rural projects observed that rural areas “tend to be more conservative and traditional, with change being slow and hard-won”. But there could also be “radical liberalism” in rural areas, Canon Triffitt observed. “It depends who you talk to. Some of our most radical thinkers would be lay leaders in rural churches who will just say ‘You just need to get real. We can’t sustain ministry like this; we can’t sustain this number of buildings. . . What you need to do is A, B, C, and D.”

In the diocese, three-quarters of worshipping-community congregations were older than 70, and many were “not far off” single figures in size, he said. The latest annual report, which warns that the diocese is “running out of easily accessible reserves”, records an ongoing annual decline of about 1000 worshippers, particularly among the under-50s. A growing number of parishes are struggling to meet parish-share commitments, and the clergy vacancy rate stands at 25 per cent.

“For nearly 30 years, the diocese has kept going only by declining and selling,” the Bishop of Salisbury, the Rt Revd Stephen Lake, told the last diocesan synod. “Now, it is time to receive help, and invest our own resources for growth.”