THE Manx Bible will be the focus of attention on the Isle of Man on Friday, when scholars and islanders gather at a conference to celebrate the 250th anniversary of its publication in 1775.

Its story is bound up with smuggling, a shipwreck, a prison cell, the political as well as religious history of the island, and the rise, fall, and rise again of the Manx language. Two revered churchmen laboured to get it translated and into print: Thomas Wilson, who held the see between 1698 and 1755, and Mark Hildesley, who held it for the following 17 years. They are buried side by side on the island.

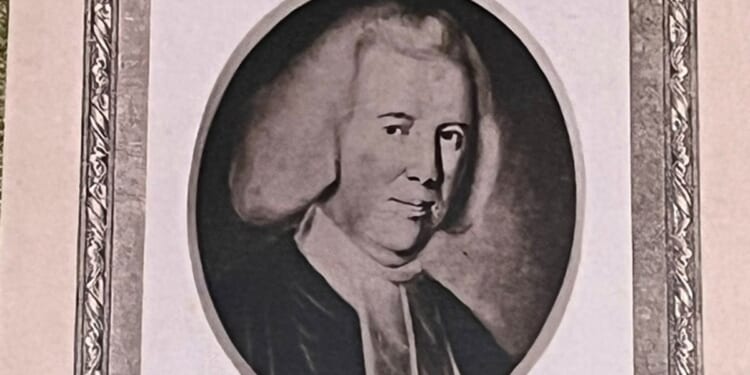

Bishop Wilson was “an iconic figure in the island’s history”, says the church historian Dr Chris Grass, an authority on this aspect of Manx history. Wilson had, at his own expense, printed St Matthew’s Gospel, and had prepared the remaining Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles for the press.

Hildesley, his successor, lamented in 1762 the lack of a vernacular Bible, telling Archbishop Drummond, “The more Part of the People are unable to attain any Knowledge of the genuine Scriptures, but what they receive from the offhand Translations produced by the Minister in the Desk from the English Bibles.”

“He thought it was terrible that the Manx church, alone of Protestant churches, should not have the scriptures in its own vernacular language,” Dr Grass says. “He never learned Manx well enough to be able to do the translating himself, but he used his position to get his clergy doing the basic work. He would go around shamelessly begging for funds to ensure that the SPCK would be able to publish the Bible.”

Not only was the Manx language looked down on, he suggests, but so were the people: “Some who had been asked for donations towards the work refused, on the basis that the Manx were ‘nothing but a nest of smugglers, and can have no religion’.

“He was also very hot under the collar about people who were raising funds for missions far away, but weren’t concerned about the needs of an ancient, episcopally governed Christian community near at hand.”

Parts of the Old Testament survived a shipwreck in 1771, when an article in the Newcastle Courant recorded that “the sloop from Douglas in the Isle of Man with 16 passengers bound for Whitehaven was drove ashore near Harrington Harbour and broke upon the beach; and the goods, parcels et cetera belonging to the Gentlemen on board were entirely lost except a manuscript copy of the Bible in the Manx language which has been above three years in translating and preparing for the press by the clergy of the island and now printing at Whitehaven.”

The last native speaker of Manx died in 1974. In 2009, UNESCO declared it an extinct language, though it was subsequently reclassified. During the past 20 years, there has been a resurgence of the language, now a marker of island identity. The island has a few families in which the children are being raised with Manx as their main spoken language. There are up to 2000 second-language speakers, and currently more than 50 children receiving their primary education entirely through Manx. The Bible Society has this year put online a revised version of the Manx Bible.

The Bible is still used on Man for language learning in a secular context: one entirely secular-language reading group meets to read it as a literary text because of the key part that it plays in establishing the orthography. There has been much interest from the cultural bodies, and the conference is organised in collaboration with Manx National Heritage.

“One of the interesting things here is that you can talk about the Bible as a cultural artefact, and you’re not made to feel you’ve got to live in some religious ghetto,” Dr Grass reflects. “For this anniversary, the driving people have been much more on the cultural than the church side, although one particular Anglican church has been very active.”

That church, St Matthew’s, Douglas, celebrated the anniversary on its patronal feast last month, when the epistle was read in Manx, and a wreath was laid at the memorial to Philip Moore (1705-83), who was educated by Bishop Wilson.

His inscription reads, “He was likewise principally concerned with reviving the memorable translation of the Sacred Scriptures into the Manks [sic] language for which by his learning he was eminently qualified.”

“Wilson consecrated the original church, and we have a very large stained-glass window to St Matthew, whose Gospel was the first to be translated into Manx,” the Priest-in-Charge of St Matthew’s, the Revd Dr Michael Brydon, says.

The congregation took away commemorative cards bearing the anniversary date and the colours of the Manx flag.