AT HER installation in St Paul’s in 2018, the Rt Revd Sarah Mullally told the congregation: “Let me reassure you, I do not come carrying bombs — or perhaps not literal ones, anyway. But I am aware that, as the first woman Bishop of London, I am necessarily subversive, and it’s a necessity I intend to embrace.”

The reference to bombs related to the campaign of the suffragettes, who, 150 years ago that week, had placed a bomb under the Bishop’s throne (News, 18 May 2018).

On Friday, Bishop Mullally was named as the 106th Archbishop of Canterbury. She will be the first woman to be placed in St Augustine’s Chair and hold the oldest office in Britain.

Her comments from the pulpit of St Paul’s point to something important about her character. Alongside the platitudes that can accompany efforts to preserve unity in the Church, Bishop Mullally has shown a willingness to name the Church’s pricklier outlines.

In a 2009 interview with the Church Times, given after she was the Chief Nursing Officer for England — the youngest holder of that post — she spoke of re-reading Charles Handy’s book on leadership, The Elephant and the Flea. “Big organisations are slow, thick-skinned, strong, powerful,” she observed. “Fleas are frisky, agile, vulnerable, and irritating. I see myself more as a flea now.”

TEN years into her episcopal ministry — she was consecrated to be Bishop of Crediton in 2015 — the difficulty of acting with agility, let alone friskiness, has presumably become apparent. Writing for the Church Times in February, she diagnosed a sickness within the Church of England’s governance (Comment, 14 February).

“In the NHS, I was clear to whom and for what I was accountable, and I was supported, challenged, and appraised by them,” she wrote. “I have tried to find this same accountability in the Church, but it does not seem to exist. . . I have gazed into the heart of the Church of England and found, at its core, incoherent governance structures, in which a number of bodies which need desperately to be joined up are free-floating.”

Amid debates about the importation of secular models into the Church — an approach frequently criticised during the Welby archiepiscopate — Bishop Mullally is likely to side with those chary of “exceptionalism”.

Her comments chime with the analysis offered by Lesley-Anne Ryder, another woman with extensive experience in the public sector, appointed to consider independent safeguarding, who told the General Synod this year that, “in the real world”, the Church’s terms of service “don’t make sense”.

In the wake of high-profile safeguarding scandals and her predecessor’s resignation, the next Archbishop will take office under immense pressure to restore trust. “Over the past ten years as a bishop, I have sought to roll up my clerical sleeves and put myself to the work of making the Church safer,” she wrote in February.

IT IS an admission that is unlikely to placate critics of her safeguarding record. It is now four years since a coroner sent a Prevention of Future Deaths report to the Archbishop of Canterbury after Fr Alan Griffin, a Roman Catholic priest who had formerly served as an Anglican in the diocese of London, took his own life over false allegations of child sex abuse (News, 23 July 2021). The coroner, Mary Hassell, warned that more clergy deaths would follow unless action was taken to improve C of E safeguarding procedures.

At the heart of the case lay a “brain dump” of safeguarding concerns provided by Martin Sargeant, a former Head of Operations in the diocese (subsequently imprisoned for fraud), whose departure from his post was connected to Bishop Mullally’s “insistence on greater accountability”, a lessons-learned report concluded.

The information from this meeting — some of which was “gossip” and none of which was accompanied by signed statements setting out distinct allegations — became the Two Cities audit report, naming 42 priests in the diocese.

False allegations about Fr Griffin were passed on to the Roman Catholic Church and he found himself to be under investigation for more than a year, without ever having the allegations and their source plainly set out for him. A vulnerable man, whose history included an attempt to take his own life, he did so in 2020.

The case raised Church-wide questions about the risks posed by a zeal for safeguarding unmoored from pastoral provision and a commitment to due process.

Concerns were aired in the House of Commons in the weeks after the coroner’s report. Lord Lexden — a university contemporary of Fr Griffin — resigned from the Ecclesiastical Committee of Parliament, lamenting that the Church had “acted on the basis of mere gossip and innuendo” (News, 24 September 2021).

In 2022, Bishop Mullally apologised unreservedly after an independent review found “significant areas of learning” for the Church, including in relation to a lack of planning, direction, and leadership. “I know that, at times, I have failed, and for that I am profoundly sorry,” she wrote in her February Church Times piece.

Speaking to the Dean of Southwark for the cathedral podcast in June, she said: “I’m very conscious that all of us have made mistakes, and I think that there needs to be a greater honesty about when we’ve made a mistake, first of all, to apologise, to try and put some of it right, and when we can’t, to understand you live with that, but also to learn from it. . . I know the mistakes I have made.”

AN INVESTIGATION into Sargeant, published in The Fence last year, portrayed the diocese that Bishop Mullally inherited as deeply dysfunctional. Sargeant’s behaviour, the investigation found, had been enabled by the sorts of failures of oversight diagnosed by Bishop Mullally in February. It also reported misogyny in the diocese: clergy were referring to her by nicknames such as “Bedpan”. One priest observed: “They can’t get away with nearly as much as they used to.”

During a 2021 debate on the Five Guiding Principles, she told the Synod: “My presence means that areas that have been fudged in the past can no longer be fudged.” Women priests were more often abused on social media, she said.

In the Southwark Cathedral podcast (“The world needs more poetry”), Bishop Mullally spoke about “Ask me” by William E Stafford, which includes the lines “some have tried to help or to hurt: ask me what difference their strongest love or hate has made”.

It was important not to gloss over hatred, or to talk only of resilience, she observed, “because actually it shapes us as much as the love does sometimes and to ignore it, I think you build up trouble for ourselves”.

She recalled presiding in St Paul’s and being struck by the many people receiving communion from her, “because, actually, my first reaction is: people don’t receive from me. Or I go into a place, and actually there are people that will, you know, the people aren’t always nice to me at the back of church, because I’m a woman and a female bishop. So I realised that . . . often I’m guarded, and I think that’s not good. That is because I’ve absorbed some of that and not dealt with it, and that isn’t good for my ministry.”

Earlier that year, she wept at the Synod while speaking about the “micro-aggression” that women experienced in the Church, in which “women’s voices continue not to be heard” (News,.19 February). “People will say I have manipulated you,” she said. “I have not manipulated you.”

In 2018, she told The Observer that she had been asked at a school “if a refusal to accept my ministry was perpetuating inequality. My answer is, there is a tension; to deny that would be wrong. My challenge [to traditionalists] is to ask: how are you encouraging women in your church, how are you making sure you’re not discriminating against them? But I respect those who can’t accept my position, and we will make provision for those who, for theological reasons, do not want to be ordained by me because I am a woman.”

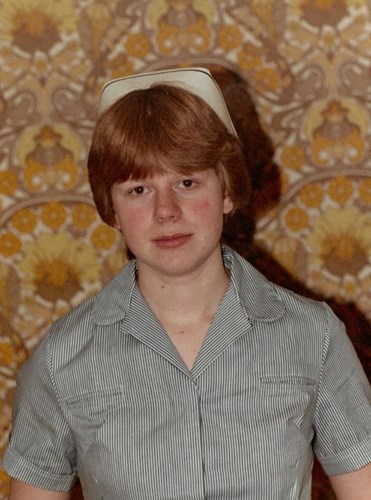

Lambeth PalaceBishop Sarah as a trainee nurse at St Thomas’ Hospital, in London

Lambeth PalaceBishop Sarah as a trainee nurse at St Thomas’ Hospital, in London

It is not only her gender that she has identified as a cause of self-consciousness. “I don’t necessarily always see people like me in the roles that I’ve done,” she told Dean Oakley in the podcast.

“Comprehensive girl. I’ve got dyslexia. You know, I was a poly nurse. I did a non-residential theological training programme, and there is a sense in which I slightly feel the Church has never quite worked me out.” There was always, she acknowledged, “a slight insecurity about who I am” held in tension with a sense that “God called me, not despite all those things, but because of all those things.”

WHEN she is installed in Canterbury Cathedral next year, Bishop Mullally will succeed an Old Etonian whose earliest memory is of tea with Winston Churchill, and who is a Cambridge graduate and worked in the oil industry before ordination. The daughter of a hairdresser (a profession that she wanted to take up as a teenager), Bishop Mullally is unusual among the Bishops in having been educated in the comprehensive-school system.

She trained as a nurse at St Thomas’ Hospital, in Lambeth, and did a degree at the South Bank Polytechnic — something that few nurses undertook at the time. Having worked as a cancer nurse, she rose quickly through the ranks of NHS management. She first appeared in the Church Times in 1998, when advertising for chaplains at Chelsea and Westminster NHS trust, where she was serving as Director of Nursing and Quality.

Having served as a senior civil servant in the Department of Health, she was not well known within the profession when she became the youngest-ever Chief Nursing Officer and Director of Patient Experience for England in 1999, and held the post until 2004. She was appointed DBE for services to nursing and midwifery in 2005. Among the challenges facing NHS management at that time were the emergence of the Shipman scandal, and the high rates of infection in hospitals.

Ordained in 2001, she served as a self-supporting minister (SSM) until 2006 in the parish of Battersea Fields, in south London. “The Church doesn’t always understand the experience and gifts that they bring,” she said of SSMs in 2019 (News, 8 March 2019). She took up full-time parochial ministry in 2004 in the same parish, and was consecrated bishop in 2015, becoming the Church of England’s fourth woman bishop and the first not to have a clerical husband.

Within a year, she had been given the task — at the request of the survivor concerned — of implementing the recommendations of the Elliott review, which considered the Church’s response to allegations of sexual abuse by the late Garth Moore, a priest and the former chancellor of several dioceses (News, 18 March 2016).

A survivor gave a critical verdict at the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse three years later: “She was kindly, with good intentions, but she was very quickly hoovered up into the institutions. She didn’t want to grasp the wider issues. . . I eventually got very frustrated” (News, 5 July 2019).

FOR the past few years, Bishop Mullally has played a leading part in steering the Church’s deliberations on same-sex relationships. Appointed in 2017 to lead the Social and Biological Sciences working group of the Living in Love and Faith process (News, 30 June 2017), she went on to chair a group of bishops tasked with encouraging people to engage with the materials that emerged.

In 2023, she presented to the Synod the proposed Prayers of Love and Faith for same-sex couples, offering reassurance that the Bishops wanted to create space for conscience, with “freedom and protection” for clergy (News, 10 February 2023). Conflict over sexuality had tarnished the reputation of the Church of England, and distracted it from its mission, she warned, “casting a shadow over our witness to Christ”.

Years of steering the process have given Bishop Mullally an insight into the depth and extent of divisions in the House of Bishops. Her account of the process to date has emphasised the need for patience and maintaining unity, alongside a pragmatism about the impossibility of resolving difference.

Last year, she warned that calls for more theology could become a “displacement activity”, given that, even with more theology, people would still disagree. Theology was not just words, but deeds.

Her position — that making “pastoral provision” for same-sex couples in the form of services offering Prayers of Love and Faith is not contrary to the doctrine of the Church in any essential matter — is a contested one (News, 24 November 2023).

But her record to date shows a readiness to work alongside others who do not share her theological convictions. A significant number of parishes in the diocese have passed resolutions under the Bishops’ Declaration, including some of the Church’s flagship conservative Evangelical churches. She has formed a strong relationship with the Bishop of Fulham, the Rt Revd Jonathan Baker, and in 2018 appointed the Revd Dr Jason Roach, then serving at St Helen’s, Bishopsgate, as an adviser. After Bishop Mullally’s appointment, Bishop Baker reassured traditionalists that he was “entirely confident” in her commitment to mutual flourishing (News, 5 January 2018).

Graham Westley LacdaoGraham Westley Lacdao

Graham Westley LacdaoGraham Westley Lacdao

“Finding ways to walk together with our diversity and differences is not comfortable,” she said in 2023, after a meeting with clergy concerned about the LLF direction of travel. “Yet I know that to separate, to walk apart, would greatly impoverish and harm the Church of England, which has always been an intentionally and uniquely broad Church” (News, 3 March 2023).

Nevertheless, she has not been afraid to show her mettle when attempts to undermine her authority have been made.

In her February piece for the Church Times, she drew attention to the “de facto distancing of churches from dioceses and the appointment of overseers through opaque means and without clarity of whom they are overseeing”, suggesting that this posed a safeguarding risk. Last year, seven men were “commissioned” for leadership positions in the Church of England at St Helen’s, Bishopsgate.

When it comes to provision for those opposed to the Prayers of Love and Faith, she opposes the idea of a “third space”, warning that it would amount to “dividing up the household of faith” (News, 12 July 2024).

IF, BY background, Bishop Mullally represents a radical break with her predecessor, the charge of managerialism is one that has been laid at both their doors. What some praise as “professionalism” and “competence” others regard as a continuation of a technocratic approach to leadership.

“I hear and understand the reasons for criticism of over-management in a top-down Church,” she wrote in February. But, “without clarity of accountability, process, and management, the people who are Christ’s body on earth do not fall through the cracks in the system: they free-fall into voids. The longer we take to address all of this, the more people we will continue to fail, hurt, and damage: the people who serve the Church and the people the Church is here to serve.”

Since taking up her post in London, Bishop Mullally has been at the forefront of attempts to reform and modernise various aspects of the Church. She was the co-author of a 2022 leaked paper on the future of episcopal ministry which argued that God was calling the Church to “embrace significant change”, including a reduction in the number of dioceses (News, 8 February 2022).

Chairing the Advisory Group for Appointments and Vocations, she led proposals calling for reform of the Crown Nominations Commission, including the removal of the secret ballot (News, 13 September 2024). It raised concerns about “pre-judgements, tribalism or politics”. Her appointment — and that of other women bishops — through this process may vindicate those who questioned the diagnosis. The proposals were roundly rejected by the Synod.

Further leadership responsibilities fell to her in 2020, when she was tasked with heading the Church’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic (News, 15 May 2020). In her own diocese, she ordered the closure of all church buildings, even for private prayers (News, 27 March 2020). The rest of the Church swiftly followed suit. Some defied the ruling (News, 24 April 2020).

Later that year, she joined Archbishop Welby in criticising the Government’s response to the pandemic as illustrative of a wider “addiction to centralisation” (News, 18 September 2020). Public worship was “an essential sign of hope”.

BISHOP MULLALLY’s translation to Canterbury will take place in a Church that has not yet recovered attendance levels since the pandemic, in which many dioceses hold less than three months’ reserves, and in which clergy are ever more thinly stretched. While some of her colleagues have criticised the current funding flows — and for greater decentralisation and a restoration of faith in parish ministry — Bishop Mullally has to date not joined with them.

Now 63, she will have the biblical number of seven years to make her mark on the Church. Inevitably, there will be talk in the press of administering medicine to an ailing Church. In her maiden speech in the House of Lords, she said: “I am the bishop I am today because of that first vocation to nursing, and compassion and healing are constants at the heart of who I am.”

Today, both the NHS and the Church of England face a crisis of public confidence and low internal morale. Restoring these will take time.

“I will not always get things right,” she said at the announcement of her nomination in Canterbury. “But I am encouraged by the psalmist who tells us that, ‘Though you stumble you shall not fall headlong, for the Lord holds you fast by the hand.”