THE work of an Archbishop of Canterbury is “complex and challenging”, but also “very simple”, the Bishop of London, the Rt Revd Sarah Mullally, said in her first address after being nominated as the next Archbishop of Canterbury.

“Along with my brother and sister bishops, I am called to share the hope that we have found in Jesus Christ and what that means for us all, as individuals and as a society,” Bishop Mullally told an audience of church leaders, local schoolchildren, and journalists.

She was speaking in Canterbury Cathedral, where a service of installation is due to take place in March 2026. Her formal election by the Dean and Chapter, which is yet to come, will be confirmed in St Paul’s Cathedral on 28 January. At that point, she officially receives the “spiritualities” of her new see.

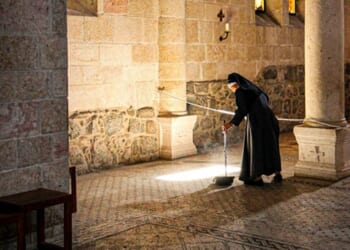

A former Chief Nursing Officer for England, Bishop Mullally said that “washing feet has shaped my Christian vocation: as a nurse, then a priest, then a bishop.

“In the apparent chaos which surrounds us, in the midst of such profound global uncertainty, the possibility of healing lies in acts of kindness and love.”

Her address, which lasted about 15 minutes, referred to conflicts around the world, in the Middle East and Africa and elsewhere, and the “horrific violence” of yesterday’s attack on a synagogue in Manchester.

“We are witnessing hatred that rises up through fractures across our communities,” she said, and the Church has “a responsibility to be a people who stand with the Jewish community against antisemitism in all its forms. Hatred and racism of any kind cannot be allowed to tear us apart.”

“Given the many struggles of our Church and of societies here and around the world, I am often asked where I see hope,” Bishop Mullally said. She found it in the “quiet hum of faith in every community, the gentle invitation to come and be with others, and the welcome extended to every person”, she said.

“In an age that craves certainty and tribalism, Anglicanism offers something quieter but stronger: shared history, held in tension, shaped by prayer, and lit from within by the glory of Christ. That is what gives me hope.”

The UK was “wrestling with complex moral and political questions”, she said, including those of “our response to people fleeing war and persecution to seek safety and refuge” and of “communities who have been overlooked and undervalued”.

She also referred to the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, against which she has led opposition in the House of Lords (News, 12 September).

When she was Bishop of Crediton, Bishop Mullally played a part in implementing safeguarding reforms (News, 8 April 2016). In her address on Friday morning, she said that, while safeguarding was “everyone’s business”, senior leaders bore an “added weight of accountability”.

“As a Church, we have too often failed to recognise or take seriously the misuse of power in all its forms. As Archbishop, my commitment will be to ensure that we continue to listen to survivors, care for the vulnerable, and foster a culture of safety and well-being for all.”

Since her ordination in 2001, while she was still working for the NHS, there had been a “significant professional and cultural shift in safeguarding”, she said.

“Our history of safeguarding failures have left a legacy of deep harm and mistrust, and we must all be willing to have light shone on our actions, regardless of our role in the Church.”

In an email to the diocese of London, where she has held office since 2018, Bishop Mullally wrote that her nomination to Canterbury was an “extraordinary honour”, but also “tinged with profound personal sadness, as I begin to absorb what I will be leaving behind. My seven years with you in the Diocese of London have truly been a joy.”

Bishop Mullally began the day in Canterbury by meeting staff and volunteers at a community larder. This afternoon, she is due to meet pupils and staff at The Archbishop’s School. She will also visit a hospice before returning to the cathedral for choral evensong.