THE Palais des Vaches is to be found at the end of a gravel track off Inchmery Lane in Lower Exbury. A sumptuously converted former milking parlour, the Gallery is part of Lower Exbury Farm on the de Rothschild family estate in Exbury and is run by the artists Nick and Caroline de Rothschild.

To arrive at this utterly charming and uniquely rural location with its magnificent views over the Beaulieu River to the Isle of Wight is to venture past New Forest ponies and bands of pheasants, down lanes dappled in sun and shadow from the light penetrating between the arched canopy of trees on the forest’s fringe. The journey is worth it for the views, the gallery spaces, and, most of all, a wonderful retrospective of work by Anthony Lawrence.

Philip Morsberger, under whom Lawrence studied at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, said of his student that “Lawrence is a Post-Modernist who knows what he is about.” This is an accurate description of a polymathic artist who combined the classical (Renaissance) with the contemporary (Pop Art) and created works that are, by turn, abstract, figurative, and a blend of both abstraction and figuration. His work frequently drew on classical antiquity, religion, and literary themes and did so whether he was working in still life, portraiture, landscape, or with religious iconography.

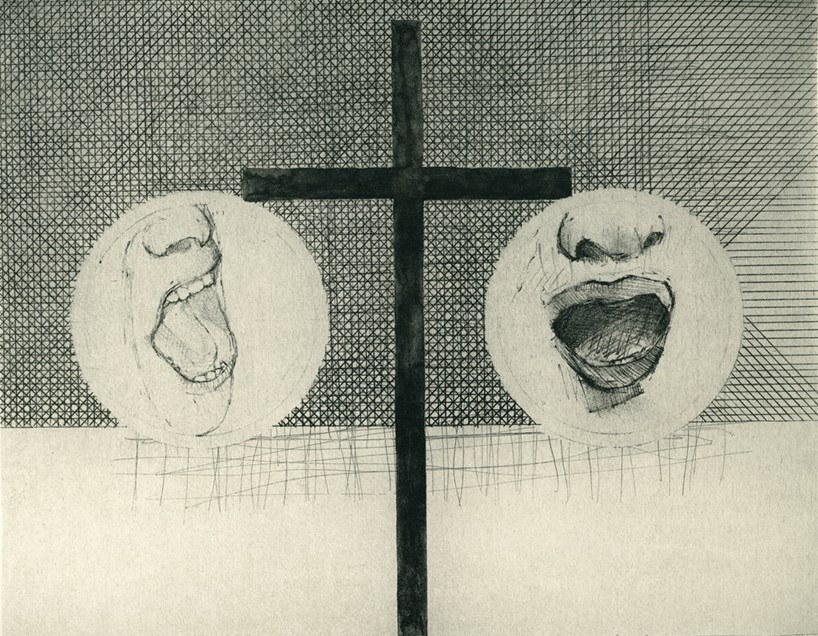

Estate of Anthony LawrenceFourth Station of the Cross by Anthony Lawrence

Estate of Anthony LawrenceFourth Station of the Cross by Anthony Lawrence

A Self Portrait from 2010 shows a paintbrush being drawn across a ruddy reddish-brown background creating a sky-shaped space within the image. This shape, often a rectangular line, is known as a blend. In this space, Lawrence blends darkness and light. He began working on his blends in 1968 when he was taken with a small section of a Renaissance painting in the National Gallery.

A particularly striking use of his blends is to be found in his Stations of the Cross series. These are of interest, first, because he includes no figures, only a single cross in each image angled, as Susan Gray has described, “against elemental skies”, together with a blended rectangular line. The inspiration for the series came from a sermon preached by Richard Harries, Bishop of Oxford, at the Royal Academy, in which the Bishop spoke about the Second Council of Nicaea, in 787, which reversed a ban on displaying figurative images of Jesus, Mary, and the saints in homes and churches. The series began as Lawrence thought of how a contemporary artist might paint the Stations should such a ban still be in effect.

Lawrence described his Stations of the Cross as being a catalogue of a cataclysmic event. His blends, by moving from dark to light balance the power of the cataclysmic sky with something calm and clear, and thereby throw the torment more into focus. In regard to his powerful “Tannhäuser” etchings, which feature many crosses, Lawrence spoke of a “constant fight between the sacred and the secular”, while Jim McCue notes a contest between “tradition and history” and “invention and innovation”. Lawrence’s Stations of the Cross feature similar conflicts with his blends, indicating potential for resolution, while also throwing such conflicts into relief.

This, then, is an example of a Lawrencian trait as noted by Morsberger: “He [Lawrence] claims that in his pictures, the questions they engage are to him more important than any answers they might advance. Lawrence asks wonderful questions!” Susan Gray, in her excellent profile of Lawrence, notes another trait, that of his combining wit with serious intent. She finds this combination present in the decorative borders edging each Station. Lawrence paints these borders “in dots, waves, harlequin and solid yellow, the artist’s ‘games with frames’, surround each work as a reminder that colour, mark making and joy in pattern are as important to the artist as the interpretation of subject.”

Estate of Anthony LawrenceTannhäuser — The Singing Contest (1996), etching by Anthony Lawrence

Estate of Anthony LawrenceTannhäuser — The Singing Contest (1996), etching by Anthony Lawrence

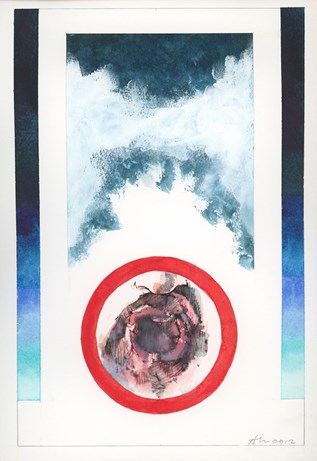

Other significant religious works include innovative versions of The Last Supper and The Last Seven Words of Christ. The former focus on the disciples’ reaction to the responsibility placed on them by Christ’s imminent death, and the latter focus on Christ’s mouth as symbol of his torment.

Estate of Anthony LawrenceFirst of The Last Seven Words of Christ (2012), watercolour, pen and ink, and graphite

Estate of Anthony LawrenceFirst of The Last Seven Words of Christ (2012), watercolour, pen and ink, and graphite

Lawrence’s supreme passion, however, was for Dante’s Inferno, a life journey as seen in In the Middle of the Journey (2005), which depicts the artist with his palette table behind him and a painting of the Dark Wood through which he has to travel in front of him. He spoke of how he was enthralled by the poetry before him and of how strange it was that a book could change a life and provide a peg on which to hang so much of a person’s life’s work.

Lawrence’s life’s work was painting, of which this large and varied retrospective is simply a glinting drop in a wider ocean. While constantly evolving through styles and series as a great “knowing” Post-Modernist, Lawrence sought, through his blend of tradition and invention, history and innovation, to hint at how reconciliation might be found in the great contest of social humanity. But, as Morsberger notes, what is supremely important in his work are the wonderful questions that he asks, questions that generated much comment when these images were first shown and that retain that capacity for all who will journey to the Palais des Vache to journey with the artist through Dante’s dark wood and do so under cataclysmic skies.

“Anthony Lawrence (1951-2022): A Retrospective” is at the Palais des Vaches, Lower Exbury Farm, Lower Exbury, Hampshire, until 31 October. palaisdesvaches.co.uk