FROM the evergreen Sunday-school action song “Building Up the Temple of the Lord” to Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, and St Peter’s Basilica, Rome, the Temple of Solomon as described in the first book of Kings has loomed large in the religious imagination for millennia.

In her book The Power of Art, the director of the National Gallery of Ireland, Caroline Campbell, describes how referencing the Temple has historically cemented religious and political authority: “The spiritual power of the original Temple has echoed around the world in the form of other sacred buildings that have been claimed to be built in its image. Reconstructing the Temple has enabled Jewish, Christian and Muslim architects and their powerful patrons to evoke the Heavenly City, in structures that reflect their times and their religions.”

Enveloped in the country house of the Rothschilds, with the family’s longstanding associations of support for Jewish institutions in Israel and elsewhere, Pablo Bronstein’s reimagined Temple of Solomon reflects an irreverent and questioning attitude to religion.

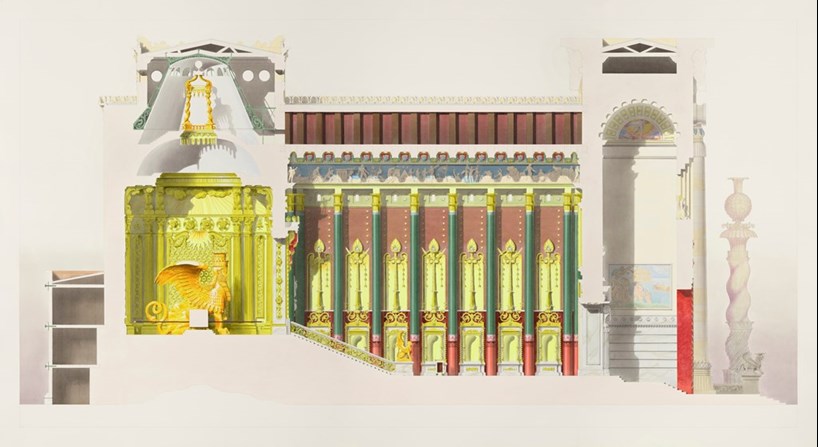

Presented in the style of fanciful architectural drawings, as if participating in the 19th-century architectural competition the Prix de Rome, Bronstein’s Temple fuses biblical descriptions of precious materials, columns, and grandeur with anachronistic architectural flourishes ranging from Baroque and Belle Époque to Gothic Revival. The monotheism of Solomon’s place of worship would have been at odds with the polytheism evidenced in archaeological findings for temples from the 900s BCE, according to the artist: “It is highly likely that were the Temple to have been built in the time indicated in the Bible, it would have been pantheistic and full or representations of the divine, as is the case with a related structure that has survived in Ain Dara in Syria.”

© Pablo Bronstein. Courtesy of the artist and Herald St, LondonPablo Bronstein, Temple of Solomon: (first version): Cross-section

© Pablo Bronstein. Courtesy of the artist and Herald St, LondonPablo Bronstein, Temple of Solomon: (first version): Cross-section

(2024-25), acrylic on paper

Bronstein emphasises his project’s seriousness in exquisitely drawn side elevations, cross sections, and aerial views, while at the same time making the reconstruction ridiculous by decorating the Temple with carved heads, representing the patriarchs, sporting long blue beards. Temple of Solomon (first version): Façade (2024-25), shows the entrance to the Temple. Above the doorway, an alcove contains representations of the Tablets of the Law held aloft by two chimeras, Greek mythological creatures with lion’s body, goat’s head, and tail ending in a serpent. Beneath the roofline, Moses with the longest beard, encrusted in lapis lazuli in Babylonian style, is directly above the Tablets of the Law, with David on his left and Solomon on his right.

Juxtaposing Babylonian imagery’s simplified, angular forms and non-naturalistic colours with facial hair reminiscent of heavy-metal rockers, together with the visual language of Greek mythology dated to 600s BCE — so not hugely distant from Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of the First Temple and the building of the Second — cannot be anything but unsettling. For faiths rooted in historical facts, places, and timelines, parallel narratives can be challenging as well as illuminating.

In a room adjoining Bronstein’s drawings, works selected by the artist from Waddesdon’s collection are on display. Designs for 18th-century candelabras, lecterns, monstrances, high altars, and churches in France show a love of ornament and the influence of interpretations of antiquity. Referencing the past while building for the future has a long lineage. Bronstein points out that Masonic imagery, evoking the Temple and ideas of the New Jerusalem, is a popular feature of American Main Streets.

A final encounter with the Temple comes from Waddesdon’s recent acquisition of seven panels depicting interiors from the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem. No similar works to these Italian embroideries, dated 1700-70, have yet been identified anywhere in the world. It is thought that they were intended for a synagogue: the richness of the materials and the sacred nature of the subject matter makes them holy objects in their own right.

In synagogues, textiles play a key decorative part, both as hangings and protection for the Torah. The embroideries’ gold and silk threads give a feeling of depth to depictions of the First Temple’s courtyard, staircase, sanctuary, and entrance columns, known as Yakhin (may he establish) and Bo’az (in strength). Spiralling Solomonic, barley-twist columns became a staple of Baroque Counter-Reformation churches.

In a white-walled box gallery, Bronstein’s Temple would read differently and more provocatively. But, in the context of Waddesdon, with its garden follies and history as a crossroads for material splendour and spiritual inquiry, Bronstein’s dissection of the Temple enlightens more than it dismays.

“Pablo Bronstein: The Temple of Solomon and Its Contents” is at Waddesdon Manor, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, until 2 November. waddesdon.org.uk