TWO later-20th-century American artists and educators have exhibitions this autumn. Mormon-raised Wayne Thiebaud, master of viscous American pies and lecturer at the University of California, Davis, is at the Courtauld Gallery, in London (until 18 January). At Clare Hall, Cambridge, a retrospective for Alan Caine (1936-2022) demonstrates the versatility of the South Dakota-born artist and theologian. He devoted his career to adult education at Leicester University, and founded the Attenborough Arts Centre, a pioneer of inclusive access.

Thiebaud and Caine represent two strands in American art — stayers and expatriates — stretching back to John Singleton Copley and Benjamin West, crossing the Atlantic for the Royal Academy and the court of King George III, followed by Whistler, Singer Sargent, and Mary Cassatt, settling in London and Paris, a century later.

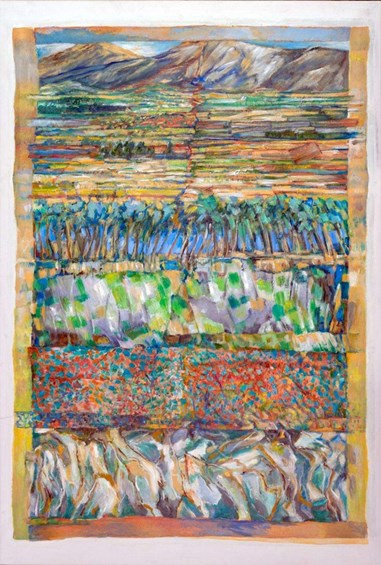

courtesy of Friends of Alan CaineAlan Caine, Mallorca (2003-04), acrylic on canvas

courtesy of Friends of Alan CaineAlan Caine, Mallorca (2003-04), acrylic on canvas

Caine first came to New College, Edinburgh, in 1960, during his theology course at Princeton Seminary. His sensibility of the wide-open American landscape is evident in Backyards Edinburgh (1960), in which a winter townscape is presented in the bleached-out tones, and outsize forms of a prairie or desert. Even the leafless trees, in black and ochre, could as easily have been blasted by the Midwest sun as by a Lothian winter. Still a visitor to Britain at this point, Caine, in his expansive vision, contrasts with contemporary artists who were painting similar scenes, such as Joan Eardley’s crowded and dark Glasgow works from the late 1950s.

Having moved to London to work with the Student Christian Movement, Caine settled in Leicester in the 1970s, teaching a full timetable in adult-education art, with Wednesdays available for his own work.

In the catalogue essay for “Everyday Wonder to Revelation”, the Revd Jonathan Evens, a contributor to these columns, illuminates the challenge of practising ministry and art: “As one who has sought through my ordained ministry to integrate culture, commerce, compassion and congregation, I am encouraged to recognise in Caine a fellow traveller, one with similar impulses who undertook his reconciliatory work in predominantly secular spaces and through understated means.” He continues: “Without reference to standard religious iconography and with a primary focus on landscape and still life, Caine imbued and infused his work with spiritual reflection and spirituality itself.”

Caine’s still-lifes are his most unequivocally spiritual pieces. In his hands, representations of everyday objects such as mops and patterned rugs become sites to tease out the perfection of the universe from surrounding clamour and noise. From the subtly hued draughtsmanship, in pencil, ink, and acrylic, of Mop (1985) to the Nodus Mundi (knot of the world) series (2012-16), the artist explores the interconnectedness of heaven and earth in day-to-day existence. Caine writes: “In Celtic illuminated pages the pulses of nature and the sense of transcendence seems to emerge from the page out of webs of line and colour, held together by the skin of bone and geometry.”

courtesy of Friends of Alan CaineAlan Caine, Nodus Mundi (2012-16), acrylic on canvas

courtesy of Friends of Alan CaineAlan Caine, Nodus Mundi (2012-16), acrylic on canvas

Mark-making to render the world visually, which is inevitably an imperfect and partial process, was a step towards the divine for Caine. “Catastrophes create broken structures. In attempts to evoke the divine, irregular marks long to become stable.”

Teaching may have deprived Caine of studio time, but the immersion in the Old Masters required for lectures shines through his landscapes. The forest motifs of Untitled, reduced to tangled, irregular shapes, recall the broken plane and earth tones of Cézanne’s woodlands, while the Tuscan and Mallorcan landscapes of Caine’s later career, including Tuscan Panorama (2010) and Mallorca (2003-04), present a striated arrangement of countryside, fusing the panoramic qualities of American landscape traditions with the consideration for formal harmony characteristic of the Northern Renaissance.

Clare Hall, designed in 1969 by Quaker-educated Ralph Erskine, is an apt venue for this retrospective. It is impossible to walk around the welcoming common room and glazed quadrangle, with its fishpond, and not feel a sense of community, complementing the optimism of Caine’s art.

“Alan Caine: Everyday Wonder and Revelation” is at Clare Hall, Herschel Road, Cambridge, until 20 November. Phone 01223 332360. www.clarehall.cam.ac.uk