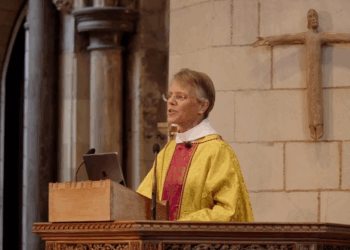

SINCE the nomination of the Bishop of London, the Rt Revd Sarah Mullally, as the next Archbishop of Canterbury, the predictable supporters and detractors have weighed in. A group of public figures have urged her to make environmental stewardship a “defining mission” of her archiepiscopate (News, 31 October).

It has taken me a while to work out my own response to her appointment. I have been out of action for the past fortnight, since I broke both arms after tripping and falling on pitted ground near Portsmouth seafront. X-rays, a scan, surgery, plaster, and three nights in hospital have left me deeply grateful for the kindness and efficiency of the nurses who looked after me: their cheerful attention to medication, vital signs, basic bodily needs, and emotional well-being.

The nursing staff at the Queen Alexandra Hospital were as diverse as could be imagined. Yet, all had developed a common “patois” by which patients, whatever their disposition, age, state, or condition, were addressed as “love”, “dearie”, “darling”, or “lovely”, which made one feel strangely cherished. There was no embarrassment, no judgement (except when I was asked whether my modest alcohol intake had contributed to my fall. Answer: No).

All this has made me reflect that there really is something extraordinary about having an Archbishop of Canterbury who has been a nurse, and who will soon be listed as a successor to Augustine, Dunstan, Lanfranc, Anselm, Becket, Langton, Cranmer, Parker, Laud, Tillotson, Benson, and Temple, as well as the more recent holders of the office.

Of course, Bishop Mullally also has considerable and serious experience of institutional leadership: she has worked in government and understands, perhaps unlike her immediate predecessor, that institutions are not a hindrance to our common life, but a necessary and vital part of ensuring both order and freedom.

After all, our institutions, at best, mediate difference and prevent our lapsing into tribalism. The Church of England is an institution that has a vocation to manage and mediate between the different theological tribes that the Reformation, for all its insistence on uniformity, never quite managed to repress. The institutions of the Western world owe much to the Christian notion of the Body, made up of many members representing different interests, and yet reconciled in Christ. Our liturgy reminds us that we are “very members incorporate in the mystical Body of Christ, which is the blessed company of all faithful people”.

It seems to me that an Archbishop who understands, respects, and cares for the human body in all its frailty is well-positioned to set the C of E on a path of healing for the Body. And it would be good for the Church itself to recover the notion that it exists as a kind of field hospital in a wounded world: less concerned about itself (numbers, money, power) than the care, and the cure, of souls.