THE Portuguese word for Bethlehem is Belém, which is the name of the Brazilian city hosting this year’s UN climate talks. Known as the “Gateway to the Amazon”, it is located at the northern end of the world’s largest river.

Many of those planning to attend the annual summit have found there to be no room at the inn in Brazil’s Bethlehem this year. Up to 50,000 delegates are expected to attend, but Belém normally has only 18,000 vacant rooms. People are planning to sleep on church floors and in converted barracks. The Brazilian Bible Society is putting up delegates on its “Bible Boat”: a religious bookshop that travels around the Amazon.

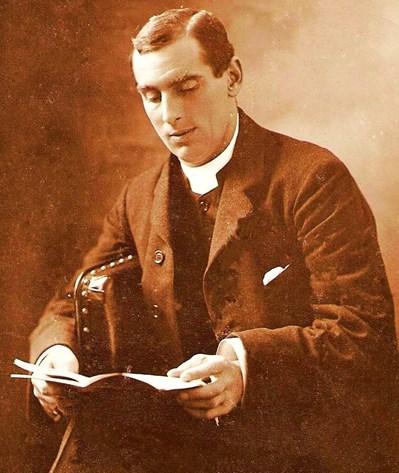

Courtesy of the Hardwick familyThe Revd Miles Moss

Courtesy of the Hardwick familyThe Revd Miles Moss

Despite the logistical headaches, there is excitement in the Anglican Episcopal Church of Brazil about the opportunity to help to make the Church’s voice heard. The Primate, the Most Revd Marinez Bassotto, says: “I believe that Churches have a prophetic and indispensable role at this conference. We cannot limit ourselves to being observers: we must be agents of change. This means acting as bridges between the different actors, facilitating dialogue and the search for solutions that respect both the environment and human dignity.”

Besides being the Primate, she is also the Bishop of Amazônia (Latin America’s first woman Anglican bishop). The majority of Brazil’s Indigenous people live in the region which is her diocese. “My work goes far beyond the religious hierarchy,” she explains. “It is based on a deep commitment to socio-environmental justice, a cause that unites my faith and my work in defence of the Indigenous peoples and traditional communities of the Amazon region.” The summit, she says, “offers us a global platform to amplify the voice of the forest and its guardians”.

“COP30” is short for “30th Conference of the Parties”. In UN jargon, a “party” is a country, and almost every nation in the world is represented. Unlike the G7 or G20, which are summits for the leaders of the world’s richest countries and last only a few days, the COP is a two-week juggernaut. Nearly 200 countries negotiate, across many different subjects, ranging from emissions reductions and climate-protection measures to deforestation, fossil-fuel subsidies, and the rules governing carbon markets.

Whereas the G7 takes place behind closed doors, the COP negotiations happen in the open. Journalists, civil-society observers, and lobbyists share the same conference venue as senior politicians and world leaders. Among those walking the halls are church leaders representing parishes, dioceses, and provinces that are some of the most vulnerable to the climate crisis.

WHERE politicians may be making decisions with their next election in mind, church leaders are likely to be thinking in terms of generations, and their perspective spans the self-interest of single nations. They seek to advocate for the poorest and most vulnerable rather than the richest and most powerful.

This is why the Anglican Communion has been represented at the COPs for many years. Martha Jarvis is the UN representative for both the Communion and the Archbishop of Canterbury. “From Fiji to Mozambique, Pakistan, and South Sudan, Anglicans see increasingly devastating and frequent cyclones, floods, or drought. In all these places, the people most affected have done little to create the crises, emitting tiny percentages of global fossil fuels,” she says.

During the COP, Ms Jarvis says, Anglicans seek to shape the narrative that informs negotiating positions and priorities, through side events, interviews, and declarations — as well as behind the scenes. “We meet privately with government representatives to discuss specific negotiating points, or to encourage them on issues that seem not to be moving. We prioritise bringing to the COPs those who are most affected by the impact of climate change and least often at the negotiating tables: youth, Indigenous peoples, and women.”

In the run-up to the COP, the Communion has put out a call to action, “Lungs of the Earth”, focusing on the restoration and protection of three particular ecosystems: oceans, forests, and ice caps. These ecosystems absorb carbon dioxide, produce oxygen, support marine life, reflect sunlight, and slow global heating.

The climate crisis, Ms Jarvis says, is something that Anglican around the Communion are familiar with. “Anglicans in the Arctic are seeing ice caps thin; Indigenous Anglicans in the Pacific Islands are working with governments across the region to reduce sea-level rise and plastic pollution; Anglicans in Kenya are embarking on a project to plant 15 million trees, and advocating to reduce deforestation; while Anglicans in the Brazilian rainforest are advocating for the protection of land cared for by Indigenous peoples.

”That gives a sense of the scale of the impact of the environmental crises, and the scale of what the Anglican Communion can mobilise in response.”

The Communion, Ms Jarvis says, will also be pushing countries on emissions. “Maintaining and planting trees alone will not do enough to prevent damage to people and ecosystems. That’s why we will also join Churches calling for countries to be more ambitious with their timelines for phasing out fossil fuels justly, as outlined in their national climate plans, which are being reviewed at COP30.

“This action is the decisive factor in global warming slowing, and needs to be more ambitious than it is now if we are to prevent temperatures rising above two degrees.”

THERE is an interesting historical side-note here, which shows that the rich biodiversity of the Amazon has long been of interest to the Anglican Church. In the early 1900s, Belém was home to the Revd Arthur Miles Moss, an English missionary whose Amazonian parish covered 1/24th of the earth’s surface.

Born near Liverpool in 1872, he was a believer in the ideas of “Deep Ecology”: finding God in the miracles and mysteries of creation. After curacies in Birkenhead and Kendal, was Precentor of Norwich Cathedral before becoming Chaplain in Lima in 1907. Roman Catholicism was dominant in the region; so Moss travelled further afield across the Amazon in search of new congregations. A keen naturalist since childhood, he seized the chance to further his study of moths and butterflies. The more he travelled through these unknown regions, the more he learned about its natural wonders.

Moss finally arrived in Belém in 1907. He helped to build the city’s first Anglican church, and stayed for 30 years. In 1945, he returned home to Liverpool for treatment for arthritis. He died in 1948, in Kendal.

Albin HillertRepresentatives of a range of civil-society groups at a People’s Plenary at COP29, held in Baku, Azerbaijan, last November

Albin HillertRepresentatives of a range of civil-society groups at a People’s Plenary at COP29, held in Baku, Azerbaijan, last November

Professor Philip Howse, the author of The Vicar of the Amazon, a book about Moss’s life, says that he was “an exceptional individual” who deserved greater recognition. “In the process of writing the book, I discovered that his collection of 25,000 moths and butterflies, as well as his paintings, had been left in the basement at the Natural History Museum, only seen by one person since his death,” he says.

“Moss was concerned about the harm being done to the Amazon rainforest even back in his day; so I’d like to think he’d be happy to see the COP summit bringing attention to its plight and the vital efforts to protect it.”

ALTHOUGH the COP is designed so that every country has the same vote on the final outcome, national delegates’ experience is very different. Rich countries from the global North send delegations of hundreds of lawyers, civil servants, and diplomats, to cover each of the different negotiating tracks with entire teams.

But poorer countries, many of them highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, may be able to send only a handful of people, some of whom have to cover several subjects at once. This is particularly tough at the end of the two-week summit, when negotiating sessions go long into the night. On the last night, it is common to see people sleeping in corridors or under desks. Sofas and plug sockets become much sought-after.

Archbishop Bassotto says that she is excited about the opportunity to strengthen the Church’s voice in the cause of Indigenous people, and to raise awareness about the Amazon. “COP 30 offers the Anglican Church a vital platform to be an active voice for socio-environmental justice,” she says.

She urges UK Christians to pray for “wisdom, discernment, and commitment” to be given to the world leaders at COP30. She also pleads with them to press politicians to pursue policies in which protecting the environment and protecting people go hand in hand. “The support of Christians in the UK is fundamental to the defence of our causes on a global level. Together, we can make a difference.”