Pablos Holman is a legendary hacker and cypherpunk whose career spans everything from helping Bill Gates fight malaria to working with Jeff Bezos at Blue Origin. Holder of more than 100 patents and founder of the venture fund Deep Future, Holman has built a life around what he calls “technology that matters.” His new book, Deep Future, is a call to “boycott dystopia” and to tackle civilization-scale challenges.

Holman backs inventors who think big: mushroom-based treatments that save collapsing bee colonies, revived Roman concrete formulas that could let buildings stand for thousands of years while cutting carbon emissions, space-based solar arrays that beam constant clean energy to Earth. For Holman, this is “deep tech” that can radically improve how people live, far beyond the incremental gains of another smartphone app.

In a September conversation with Reason‘s Nick Gillespie, Holman talks about why the world needs a tenfold increase in energy production, how we mixed up policy on nuclear weapons and nuclear power, and why we should accelerate artificial intelligence (AI) development rather than slow it down. Holman’s optimism is infectious, and he invites people to imagine and build a world that refuses to settle for scarcity or stagnation.

Reason: The book is subtitled Creating Technology That Matters. What is technology that doesn’t matter?

Holman: We live in this world we think is full of technology, but it’s mostly just full of software. I think we’re setting our sights a little low the last couple of decades. If you just have iPhone apps to have weed delivered to your dorm room by a drone, that doesn’t really feel like technology to me. Meanwhile, it’s taken our attention away from other technologies that could make a bigger difference.

Nobody loves software more than me. My best friend from childhood is an Apple II. It’s turned out to be this incredible tool that we can use that’s generally applicable to everything, and that’s important. But now that we’ve done software to everything, we need to get back to doing the other stuff.

So when Marc Andreessen says that software is eating the world…

I say the world can’t eat software. If you think about food, clean water, sanitation, construction, manufacturing, energy, all these things every human on Earth relies on, you won’t radically improve them with software. You can make them a few percent better, and we are doing that, but you’re not going to make them 10 times better. That’s what I think of when I’m talking about deep tech—technologies that could go after those bigger problems.

You run a fund called Deep Future. What are some of the companies you’re investing in?

We invest in these mad scientists—they’re coming out of a lab and into a startup, and most of them have some kind of breakthrough or we wouldn’t bother. One in New York. These guys figured out that plants protect themselves from bugs using this mushroom spore in nature. They’ve been able to take that mushroom spore and evolve it to target different invasive species of bugs. They’re using it right now to save bee colonies from the Varroa mite. The reason bee colonies are wiped out is this little bug called Varroa mite eating the bees. Well, they put a teabag of mushroom spores in the beehive, and it will wipe out the mite and save the bees. It’s this amazing, beautiful thing, but it’s not software.

What about the Roman concrete? I was in Rome earlier this year for the first time and was amazed looking at the Colosseum, which is still around after over 2,000 years.

Or the Pantheon, which is even more miraculous. If you’ve seen that thing, it’s like the dome building in Rome, it’s 2,000 years old, it’s made of unreinforced concrete, and it’s in a seismic zone. Everything we build out of cement—which is almost everything we build—is made of concrete with steel rebar to reinforce it, and then it crumbles in 50 years. Nobody’s ever been able to figure out “How did the Romans do that?” I found this guy at MIT who figured it out. Now we can make cement that lasts virtually forever, use less of it, use less steel, and the kicker is, it’s less CO2. There’s nothing not to like about this. And you could do it at any cement plant. It doesn’t cost more; you go in and change the formula a bit.

Now they’re in production. They’re building stuff with this cement. [In] less than 10 years, we can probably upgrade all the cement being produced.

A lot of the companies that you discuss in Deep Future have to do with energy. You talk about a company that is going to use solar power by being in space where the sun never sets. Can you explain what they’re doing?

If you just look at what’s happening with our solar farms, we keep making more and more of them but the relentless onslaught of night keeps fucking with our solar panels. But if you take the same solar farm and launch it into space, it’ll get sun 24/7. It’s actually noon in space all the time. If you put a solar panel in space, it’ll get sun all year long—eight times as much energy—and then you can beam it down to Earth using radio waves that go right through clouds. This sounds like science fiction, I know, but it’s real. All the technology, we have. They’re aiming to put the first commercial array up in four years.

Is there a regulatory regime or exorbitant costs slowing it down or preventing it from happening?

We actually have a pretty functional regulatory situation for doing things in space. So that’s less worrisome than it has been in other industries.

The cost of putting stuff in space was just laughably expensive for our whole lifetime. In a space shuttle, it would’ve cost $40,000 to get this book into space. Now it’s about $1,500. But the target that SpaceX has for their big rocket is $10 a kilogram. In this lifetime, you’ll store your old sportsball gear in space instead of your garage or closet.

Do you really believe that?

Yeah. It’s called space for a reason. We’re really going to do that.

You determined that energy production is the most important thing to improve life on Earth for the most people. Is that because as we get richer, we consume more electricity?

We consume more energy because we’re rich, but a lot of people don’t have enough. They need to consume more energy, not because they’re rich, but because they need it. If you average global energy production, let’s say you get about one toaster per person—you duct tape the button down on a toaster, run it 24/7—that’s about how much energy the average earthling gets. Americans get eight bonus toasters. You’re literally getting an insane amount of investment of energy in every single American to get those averages. Three billion people live on less than one toaster.

We’ve made enough energy for all the people in the West and north of the equator, but we just haven’t finished the job. Less than one toaster is not an acceptable living standard. You want to get somebody up at least to—Europe used to be five, six toasters, now they’re more like four or five, but that’s an acceptable living standard. To get those averages up, we’ve got to 10X global energy production. And that’s kind of heretical. Most people want to show a couple of percent a year of growth.

Or they want to manage demand for energy rather than increase the supply of energy?

Yeah. It’s a complete red herring. Just try to cut your power consumption by one or two toasters. That’s the max you could do without starting to feel like you live in a Third World country. And at the other end of that, we’re at less than a toaster trying to go up, so we have to provide for these people. And you can’t overstate how important it is. What are people fighting over? What are all those wars about? It’s access to energy. It’s control of those resources, mostly oil. If you could provide a death ray from space full of clean, cheap energy to people, then what are they going to fight about? Dumb shit on Twitter like Americans do.

Can you explain your theory about nuclear energy?

I worked at a lab called Intellectual Ventures years ago, and we invented the most advanced nuclear reactor, called TerraPower. If you see Bill Gates talking about nuclear reactors, that’s the one.

In about 2007, and every year since then, we’ve been unable to get the U.S. government to approve it to build a test core. Nothing wrong with the reactor—it’s just the U.S. government has no way of approving any new reactor technology, and the only thing they could possibly approve is old reactor technology. I have a lot of scar tissue from that, because I’ve been trying to convince people that nuclear reactors are coming for almost 20 years, and I’ve been wrong all those years.

But this last year, things really radically changed. Last year a huge bipartisan bill was passed called ADVANCE to push for developing nuclear reactors in the U.S.

Last month, Trump signed like four executive orders to push deploying nuclear reactors. And all the hyperscalers woke up and realized, “Oh, to power all these chips we got from Nvidia, we’re going to need some nuclear reactors.” I think the world has radically shifted in the last year.

In the book, you talk about how nuclear power and nuclear weapons got conflated. Also, if you talk about nuclear power plants, people think of Three Mile Island and the film The China Syndrome. And you throw some shade on the “No Nukes” concerts of the late 1970s. There are no positive examples of nuclear reactors in popular culture.

Actually, 13 percent of our energy comes from nuclear reactors in this country. That’s [a] quite positive example. You don’t know anybody who lost their life to nuclear reactors. You do know people who lost their life at least early from the pollution from burning coal and gas.

Humans are story-powered creatures—and when we get a story in our head, it controls us. The story we got in our head was we mixed up nuclear reactors and nuclear bombs. We outlawed the wrong one. If we’d done it the other way around, you never would’ve heard of global warming. That’s what’s possible, and we’re still not being honest about that. It’s time to get a new story.

The cool thing is my kid thinks Chernobyl is a TV show for old people. You have to wait out the story for generations sometimes. But we’re at that point now. I kind of want to see if I could get Bob Dylan to help us do a “Go Nukes” concert.

“Go Nukes” would be awesome. Do you think there’s an argument that even if we had cheap, nonpolluting energy, we just shouldn’t consume that much of it because it’s wrong to be rapacious or gluttonous in our energy production?

Yeah, but there are other things we do where we’re rapacious and gluttonous for generations, and then we learn to get it under control. I think you have to think about a lot of these technology adoption cycles as a life cycle. We’re in maybe junior high with social media—still pretty poorly behaved. We’re barely in preschool with AI. But for some things, like email, we pretty much got under control, not to mention fire and knives and all the other shit you could really do some damage with.

These things—we’re impatient, but you have to learn to get them under control. Everybody overdoes it a little bit with drugs and alcohol, and most people sort of figure out a functional relationship with it. And then there’s some collateral damage along the way.

Can you talk a little bit about your vision for AI?

I think of AIs as computational models. Your brain is running those simulations, and now we can make those models in the computer. We can simulate our world better and better and better.

We did this in our lab for epidemiology, and that’s the thing that inspires me the most. We started this 15 years ago, advising half of the countries in the world on how to optimally deploy their vaccination resources and epidemiological interventions. In the first Ebola outbreak, 12,000 lives were lost. In the second Ebola outbreak, a few years later, only 12 lives were lost, in part because, using these models, we can get the better answer about how to contain that disease before it spreads. That’s what would have been possible with COVID, but we weren’t trying.

Why weren’t we trying?

We tried to raise the alarm. We had Bill [Gates] do a TED Talk about it in 2015. I looked in March of 2020—right before COVID broke out—and 6 million people had watched it. I have pointless TED Talks that way more people have watched. We should have got a Kardashian to do the TED Talk. We couldn’t get people to worry about a problem that, for Americans, is imaginary.

I think you want to think of these as tools to help you make better decisions. Now, you could still make dumb decisions, but at least you would know that’s what you were doing. You can’t plead ignorance anymore.

Google Maps is an AI you’ve been using every day even though you know how to get to work. Because it knows traffic. It knows the best, fastest way to get to work. It has more data than you, and it can analyze all that data. It can give you a blue line—here’s how to get to work—but then it gives you a couple of gray lines. If you want to stop for a burrito or pick up some Starbucks, it’s showing you these are your possible futures and you choose the one you want. That’s the relationship we should have with AI.

You call for an AI war of escalation. Most people say we need to slow down or we need to make sure China doesn’t do too much.

Right now, the guys who are building AIs are being kind of disingenuous. Most of them, in my view, they’re saying, “AI is super powerful, but it’s so powerful that nobody else should have it except for us.” I think that’s a lot of bullshit. What should happen, and will happen, is we’ll build a multitude of AIs. Mine should be checking yours. Yours should be checking mine. We should be competing. We should figure out over time, which one do you trust? I trust the people who built this one. I trust the answers this one has given me for years. You build trust in it, the same way you do with a human.

It’s really the wrong track to get on to build AI in the image of how we built social media. Why would we do that? Why would we let a few companies control it? They’re in the race to spend as much as possible, because they don’t really have a moat. There is no moat in the tech. We all have the same algorithms. We can all build a ChatGPT ourselves. What we can’t do is get as much compute as OpenAI, or Meta, or xAI; they’ve got the compute. And now even the compute isn’t a big enough moat. Now it’s trying to control access to energy again. We’re right back to the same wars we were having in the Middle East over energy, but now it’s hyperscalers trying to buy up every last electron that you can get.

You’re 54, and you grew up in Alaska. How did you get into computer programming and digital culture, and how do you maintain an optimistic view of technology?

When Apple shipped their first computer that you could have at home, the oil industry was the biggest, richest industry. My dad had put some of the first computers in the oil industry. When Apple needed customers, they’re like, “Hey, want to buy some of our totally useless but expensive little computers?” And he’s like, “Sure, we’ll take one.” So I got one of the first computers Apple ever made, and it was in Alaska, which meant that nobody for a thousand miles had ever seen a computer. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I just had more time because I was in the freezing cold, so I would just crash it and reboot it. That’s how I learned.

Apple II couldn’t even do graphics. It’s just text. The operating system and your program and your data all had to fit on a disk that held 240,000 bytes. That’s not very much. At the time, I just wanted to convince people this thing was going to be amazing and useful, and nobody believed me because it wasn’t. I had a skateboard, and they’re like, “That has more promise. You should just go waste time on the skateboard, get out of the house.” I was right. The Apple II did kind of suck, but it eventually got more memory, and it got faster.

I reverse-engineered my way into computers. That’s totally not what you should do. Nobody does that, but I didn’t know better. Once you know what the zeros and ones are doing, then every new thing computers could do, I just had to learn the new stuff. I’ve been doing that my whole life.

What happened that turned this generally optimistic outlook to one that is really harshly pessimistic, and how do we move past that?

In 2006, any of you who are on the internet probably had an RSS reader. When I subscribe to your blog, every day, my reader goes and grabs whatever you put on your blog. And if I subscribe to all your blogs, it goes out to each one and grabs whatever is in your feed. And then my reader gets too much crap in it, so I make filters like “minus Trump,” “minus Biden,” “minus Elon,” minus whatever pisses you off.

I, to this day, use RSS, because it still works on every website on the internet. I have this feed of news that I have tuned over decades now, and I don’t get the things I don’t want. I only get the things I chose, and I control the knobs and dials.

What happened to the mainstream is they went from this beautiful and open system and ran into a big walled garden called Facebook. And Facebook does not give you the knobs and dials. They don’t let you control your feed. They came up with their algorithm that thinks somehow they’re magically going to come up with one set of values for everyone on Earth. We all opted into this, and I guarantee you, we don’t all agree about shit.

I just think what we did wrong was fell for this story where we’re going to let Facebook determine a value system for all of us and we keep beating them over the head. We’re like, “You got to stop letting this content…you got to stop letting that content…you got to do more of this and less that.” And we do it to Twitter, we do it to everybody, but we’re just on the wrong fork in history. The right fork in history was RSS. Don’t give your attention to what seeks you. Save it for what you seek.

If we’ve gone down this dead end, how do we back up?

Any technology that humans invent and figure out and prove that it’s good and economical, we always adopt it in the long run. Whoever invented the wheel was probably assassinated. Then, for a few generations, “Kill off all those assholes with wheels.” But then, a few generations in, “Fuck you, Dad. Wheels are cool.” And then the technology gets adopted, normalized, and everybody gets it.

We’re at this developmental stage where we got drunk on Facebook and went nuts with that. But like the story I told about nuclear reactors, we’re going to evolve past that because these are better ways for humans to organize ourselves. That’s what decentralization is.

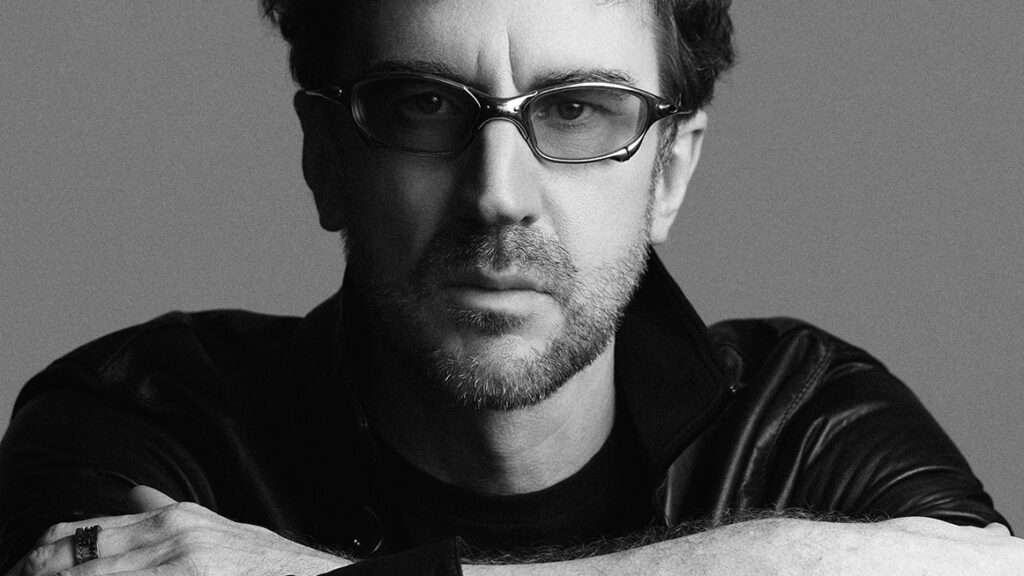

Final question. Your glasses are cool—futurist and retro, all at the same time. How long have you been wearing them, and where do you buy them?

Back in their heyday, the designers at Oakley were like gods. They built this factory somewhere where it was not under a lot of scrutiny, and they could do investment casting, which is an expensive way to cast titanium alloy. And they made the coolest glasses ever made, the toughest glasses. I’ve been wearing the same pair for 20 years. But the factory blew up because of all the volatile gases in the casting process. Nobody will ever make glasses this way again.

But they’re the best ones ever made. Because I’m in a lab all the time, I have to wear safety glasses anyway. These correct my peripheral vision and they fit and they don’t break and they don’t fall off my head. And for years, people thought they were weird. Now I get compliments.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity.