AT LEAST once a year, news of congregational conflict overflows the parish boundaries and makes it into the newspapers. This summer, it was the turn of the diocese of Chester. The Bishop, the Rt Revd Mark Tanner, sent an excoriating letter to a volunteer bell-ringer after “libellous” flyers, attacking both him and the Rector, were glued with permanent adhesive around the grounds of St Oswald’s, Malpas (News, 30 May).

Not unusually, the truth of the situation remains unclear, and the diocese recently announced that the Bishop of Birkenhead had been commissioned to carry out a “health check” of the parish (News, 31 October). But media reports suggest that the rift began after the Rector, the Revd Dr Janine Arnott, told the choir that they could no longer sing the Agnus Dei in Latin, and that bell-ringers had had their access to the bell-tower restricted. Bishop Tanner’s missive condemned “infantile” and “bullying” behaviour.

Readers of last year’s General Synod motions on tackling bullying by lay officers may be inclined to believe the Bishop’s account (News, 1 March 2024). Members heard stories of fists slammed on tables, lay churchgoers who felt that they “owned the church”, and clergy leaving their ministries. Others will see things from another perspective, thinking of clergy who are bullies themselves or have, at least, driven through change with scant regard for consultation.

Most clergy have experienced “active resistance to change” during their ministry, the ten-year study Living Ministry suggests. The latest wave, which explored how the clergy manage and lead change (News, 23 February 2024), heard that opposition was most commonly evident in the form of PCCs’ questioning or refusing to endorse the proposed actions.

Resistance was “often understood as an aversion to change in general” by the clergy who participated, and one observed that the Church was “full, in my opinion, of quite conservatively minded people”. The part played by the previous incumbent in shaping practice was mentioned, and the refrain “We’ve always done it like this”; but the “fear of change and loss” was also identified, linked to a “wider and less defined anxiety about the world in general”.

NICK (not his real name) has been the rector of a rural benefice for eight years. At his interview, his impression was that the benefice was “an odd place”, but that it was also “a great job. All I’ve got to do is this and this and this. Five years later, I hadn’t even done a quarter of the things that were pretty straightforward, just in terms of governance.” Trying to introduce financial planning — something that seemed like “basic stuff” — met with huge resistance from a treasurer who threatened to resign. It has taken years to agree to set a budget.

One of the challenges of ministry, he reflects, is that you tend to work with volunteers rather than employees in an professional environment. “You come up with a suggestion . . . and then realise it’s not happening, and you don’t quite know why. And there are all sorts of reasons why it’s not happening.”

BEN CAHILL-NICHOLLSThe Revd Ben Cahill-Nicholls blesses children’s backpacks at Tilford Parish Church

BEN CAHILL-NICHOLLSThe Revd Ben Cahill-Nicholls blesses children’s backpacks at Tilford Parish Church

Some lay members were “completely open about the fact they had bullied the previous vicar and were almost quite proud. . . That was the culture I had inherited.” The culture changed as a result of “holding my nerve and people leaving”, he says. “That is what brought change about.”

Nick was disappointed not to receive support from his diocese. Safeguarding training focuses on “everybody, apart from the vicar”, he says. “I’ve had people scream at me in meetings. We are not meant for this.” A clergy colleague reported that an effigy had been made of him and placed on a bonfire. “This is why clergy become quite tough and quite thick-skinned, and perhaps less pastoral.” When it comes to change, “People feel their whole identity and whole reason to be is under threat,” he says. “It’s deeply unchristian.”

For new incumbents, it can be difficult to judge when to make changes, he says. “If you leave it too long, you get sucked into the culture, and it gets harder to change; but, if you go soon, it implodes.” Building trust and relationships takes longer in a rural community, he suggests. Looking back, he believes that he should have spent more time on this. “One-to-one cups of tea — that is what does it. . . They are not bad people: they are anxious and worried.”

IT IS hard to avoid talk about the necessity of change in the Church of England in the 2020s. In the wake of the Renewal and Reform programme, which offered multi-million-pound grants to dioceses for large-scale change projects designed to turn around numerical decline, many diocesan visions and strategies offer variations on a theme: “Time to change together” (Lincoln); “Transforming church. Together” (Bristol); “Transforming Church, Transforming Lives” (Guildford).

But, ten years into the programme, evaluations have begun to highlight just how difficult change can be to enact. The independent Chote review of the SDF programme heard from dioceses about “a realisation of the difficulty of culture change in the Church and the level of resistance that was experienced”. An early summary of “learning points” in 2018 concluded that success was more likely if senior clergy were “prepared to show disruptive leadership to address blockages and persistently communicate a vision for change”.

More recent reports appear more attuned to the need for patience when it comes to making changes. “Bringing congregants on the journey of change can accelerate growth and revitalisation, whereas not bringing them along can slow or hinder change,” the latest Strategic Investment Board report advises.

“Many churches operate within a culture that has developed over many decades, and an aim to change that in a matter of a few months or even years will result in disappointment,” observed the lessons-learned review of Ely’s Changing Market Towns project. A recent review of learning from rural projects, What’s In Our Hands, observed that rural areas “tend to be more conservative and traditional with change being slow and hard-won”, warning that “any proposed change is a criticism of the status quo and is likely to invoke defensive responses.”

There is a marked degree of realism in some of these reports. “Grafting a new families’ work on to an existing more elderly congregation who are reluctant to change is unlikely to work well,” the Ely report warned. An evaluation of the “Intergenerational Missioners” project in Hereford highlighted the difficulties that many encountered in their placements, and the challenges of securing “practical congregational ‘buy-in’ to mission”. The “turbulence” created by the project should nevertheless be celebrated, it argued. It had prompted hard but necessary conversations.

THE Revd Paul Rattigan, who retired last year after a 30-year ministry, took up his first incumbency during a period when “massive” reductions were made in central funding for Liverpool diocese, resulting in cuts to stipendiary clergy. Decisions about where these cuts should fall were delegated to deaneries, and he and another incumbent were given the task of drawing up models to present. “The model that was voted through was one where there was shared pain,” he says. “Nobody was seen to benefit or suffer much more than another.” Other models may have been “better strategically”, he says.

When it comes to communication about the need for change, he advises repetition: “You say it until they can say it back to you, the way you are trying to say it.” Open meetings, where people can ask questions, are also critical.

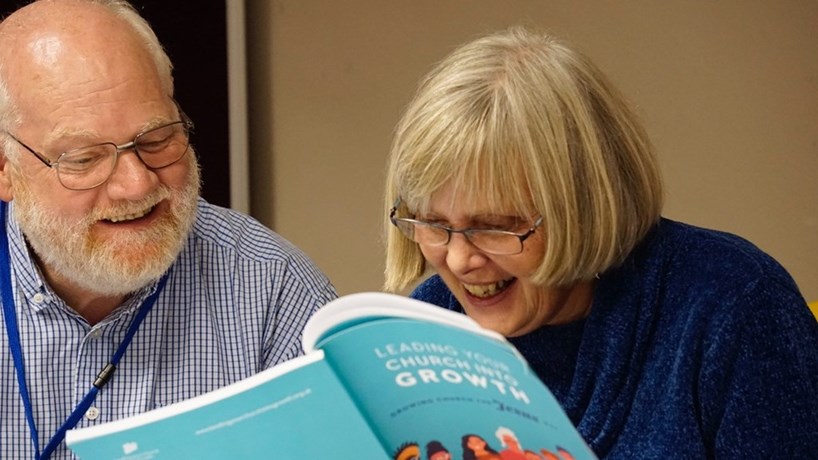

LYCIGA LYCIG conference

LYCIGA LYCIG conference

Every parish has its “quirk” that needs to be identified, he says, and change can come in unexpected ways. The church where he had his second incumbency had burned down in the 1960s — a “major spectre in the background” that was raised regularly. Every new incumbent was shown a film of the fire and the rebuilding process, made by a family living opposite the church on an 8mm camera. Showing it publicly during the service marking the 40th anniversary of the fire proved to be “so cathartic”, he says. “The fire was never mentioned after that.”

For new incumbents, he recommends Ten Commandments for Pastors New to a Congregation, by Lawrence W. Farris (Eerdmans, 2003), and its advice that “When you walk in you have a certain amount of goodwill. If you walk in and find there are any blockages, you have to decide, is this something that I need to use my goodwill to tackle early on?”

The congregation must be listened to, he emphasises. “They will have been there before, they will be there after. . . They have invested hours and time and money and emotional energy into that parish. You ignore them at your peril.” It’s also advisable to pay attention to those “in the middle” of the train, in an analogy in which those pushing for change are the engine and those most opposed form the brake.

THE Living Ministry study found that clergy “tended to show more awareness and desire for change than knowledge of how to bring change about and ability to implement it”. Given a list of aptitudes for change management, about 40 per cent did not identify with “edge and tension”, defined as “moving towards and amplifying disturbance in order to shift capacity to perform to potential, by naming reality and confronting tough issues, especially strongly held assumptions and ways of working”.

But about the same percentage identified with “leader-centric” behaviour, defined as “being overly controlling, wanting to be seen as the ‘mover and shaker,’ and leading from one’s own beliefs rather than the organisation’s purpose”.

The study’s authors offer a note of caution about the risks of importing a model designed for employee-staffed organisations into the Church. They observe that “managing change with volunteers, as most clergy do, is likely to entail different dynamics and may render disruptive methods more risky, while introducing ‘edge and tension’ may run counter to the pastoral nature of ordained ministry.”

The study heard that some clergy had had to resort to legal arguments, such as the priest who, when challenged on moving baptisms into Sunday services, quoted canon law. Another had to take “unilateral action” to correct financial mismanagement, after failing to persuade the PCC.

A common strategy described by participants was the introduction of change on a trial basis. Sometimes, change involves disrupting relationships by challenging individuals or groups, the report observes. It mentions the case of a vicar who “called the bluff” of a group who threatened to refuse to run a special service if they had to compromise on certain things.

FOR some clergy in the study, an obstacle to change was congregational demographics: elderly volunteers, fearful that nobody was available to pick up the baton, had to be encouraged to set down responsibilities. Others spoke of disappointment with a lack of participation, and the outworking of clericalism. One described their church as “like a little club where they come together on a Sunday morning and get together. They’ve done the God thing, and they can put God back in the box until the next time we meet. . . They haven’t really grasped the idea that they’re actually disciples. They’re not just churchgoers.”

LYCIGThe Revd Felix Smith

LYCIGThe Revd Felix Smith

Some new incumbents have spoken of discovering, on arrival, that they needed to evangelise their own congregation. Nick believes that “folk religion”, with which the Church had been “complicit” for decades, was dominant in his benefice. “We forget that we are a community of people gathered around Jesus.” But he has learned to be “more sensitive” towards such religion. “When you dig a bit deeper, people surprise you. People you think are worshipping a building . . . are just very reticent about talking about faith.”

It is a quotation that illustrates the different theologies and cultures that can be operative in a parish, which can be decades, or more than a century, in the making, and require a degree of mutual understanding, particularly when a new incumbent is formed in a different tradition from that of the congregation. Change is being enacted against a backdrop of calls for culture change on a national scale, with the Vision and Strategy calling for a Church of “missional disciples”.

Meanwhile, diocesan restructuring often entails another form of culture change, grouping parishes into larger units and pushing for greater joint working and a sense of shared identity.

Speaking two years ago to the Church Times (News, 8 September 2023), Canon Simon Butler, then rector of a 12-church rural benefice in the diocese of Winchester, observed that investment in a parish church could be greater for those with a “more sentimental attachment to the Church” than for those “whose primary driving force is a theologically articulated professed faith.” For the latter, moving around different churches might be easier “because there is a greater sense of being part of the broader body of Christ”.

In rural areas, however, there was often “a very strong sense of devotion and strong sentimental attachment to a particular place as consistently manifesting God’s presence, and that has to be taken really seriously and not suggested that this is a second tier of faith.”

“NOTHING involving humans is absolutely static, because people change, life changes, technology changes,” Prudence Dailey observes. She has represented the diocese of Oxford in the General Synod’s House of Laity since 2000. “But it depends on the type of change, the extent of change, and the speed of change. A lot of change is based on the premise that ‘We must do something; this is something; therefore we must do it.”

She quotes G. K. Chesterton’s story about reformers’ taking down apparently needless fences without considering that they must have been built for good reason; the “unintended consequences” she has seen flowing from changes made by the Synod; and the difficulty of then undoing them.

“It is always easier to drive people out than to bring people in,” she says. Her own vicar, in Oxford, has made changes — “introducing new things without getting rid of things people love” — and brought in new people without losing older members, “because the changes that have been made are with the grain of what people wanted”. Changes should be made “incrementally”, she advises. “Do it at a speed that people will accept. And some changes people just won’t accept and shouldn’t have to.

“If somebody is going into a church with a brief to shake it up completely, and make it something quite different from what it is already, they are in the wrong place. They are being put into an impossible situation.” She advises clergy to “listen to people’s concerns, and start from the assumption that they might know something you don’t, because they have been there longer.” If a PCC is adamantly against a change, it is better to wait, she suggests. Changes may take time.

The impression sometimes given by the communications of the national Church and dioceses is that “actually they don’t want the congregation that they have got”, she remarks. “These are the people, as church attendance declines around the country . . . who have been faithful, who have carried on going week by week. . . A lot of them are in their declining years, and can’t face a whole lot of radical change. They just need some spiritual comfort. . . I have seen where those people are treated with respect, and growth can be achieved in a way that makes everybody happy.”

THE Revd Felix Smith was appointed associate director of Leading Your Church Into Growth (LYCIG) this year, after an eight-year incumbency as Rector of St Michael and All Angels, Lancing, during which time he took on responsibility for two other churches. Respondents to a LYCIG survey spoke of “resistance to change” as the biggest obstacle to church growth, he reports. “The congregation don’t want the church to close, but would rather the change that needs to happen happen when they have gone,” one commented.

Behind people’s resistance can lie a multitude of factors, including “so many examples they have seen around them of change happening badly”, Fr Smith suggests. Churchmanship may also be a factor, where congregations believe that “this change means that we are going to turn into a certain type of church, which can often be the HTB model.” This was a concern for some when his Anglo-Catholic church introduced screens.

PAUL RATTIGANThe Revd Paul Rattigan

PAUL RATTIGANThe Revd Paul Rattigan

It can help to explain that changes are not about changing a church’s identity, but “sharpening our identity, or re-finding some of the traditions that we used to have”, he says. When taking on responsibility for another church, he asked for a tour of the church and was able to express enthusiasm about its history (“That’s amazing! Where did that come from?”).

He asked the PCC about when the “positive times” were, and what had happened since. In the early 1990s, attendance had been 120, but that this had fallen to just ten. The message he had to deliver was: “You can’t keep going in the way that you have been going; there has to be something new, something different, and that will have some positives and some things you might not like as well.” It helps to expect “a degree of anxiety and degree of kick-back”, he says. “If you know the cost of change, it is much easier when it happens.”

Making changes is easier when done with a “cockpit crew” who are “really on board and on message in terms of why changes are happening; so a lot of the questions and issues are not just directed towards one person,” he observes. “If the congregation is thinking ‘The Vicar has changed this, and the congregation are all against it,’ that becomes really toxic.”

It can also help to work with nostalgia for a much-loved previous incumbent, he suggests, getting a congregation to list all their good works and any changes that they made. “You start to make them realise that the last time they were in a period of great growth and things were working at their best, it was a time when change had happened. Part of selling the vision is not always just looking forwards, but looking backwards. What did we lose that means things aren’t so good now?”

LYCIG — which received £750,000 of national funding last year to help more parishes — is going to be offering follow-up work with parishes whose representatives attend its courses, helping them as they put into practice their plans for change. The Church needs to put more thought into how it prepares people for change and leadership, Fr Smith suggests. “I have seen lots of clergy go in really fired up, almost relishing the conflict, almost as a kind of badge of honour. . . There needs to be a subtle and more generous way of managing these things.”

SOMETIMES associated with the Evangelical tradition, LYCIG actually serves a wide range of parishes, Dr Smith reports, and it is updating its materials to reflect a broader range of traditions. It is run by clergy with plenty of experience of parish ministry.

The charity’s national director, the Revd Sue Cooke, recalls that, in her first incumbency, she led the congregation through a process of analysing all its activities, why they were being run, and how it would feel to stop some of them. The Mothers’ Union closed with a “great, celebratory” closing event. “We always celebrated people giving stuff up.” In a small church, she felt able to pre-empt whoever would oppose changes, and would have a one-one-one conversation with them to explain the rationale, offering them the opportunity to talk further after trialling the change.

In her second incumbency, when she had to make the “really difficult” decision to close and sell a church — never consecrated — there were petitions, with her face on them, put up in local shops “about how awful I was”. One woman and her husband wrote letters to the Bishop, MPs, and the Archbishop. “You have to just learn to hold your nerve and ask ‘What does God want?’” she recalls. “What do I think is the better long-term picture?” The £3-million proceeds from the sale have enabled the purchase of two flats to house children’s workers. “Sometimes, it’s short-term pain for a longer-term gain.”

LYCIGAn LYCIG conference

LYCIGAn LYCIG conference

A Living Ministry participant commented that one of the biggest risks in any sort of change was “disillusionment if things don’t go as hoped”, referring to a breakfast club run by volunteers to which “hardly anyone came”, leaving them disappointed.

“Not everything will work,” Ms Cooke counsels. “But it’s better to have tried, and had one person there, than do nothing and have no people there. We expect results really instantly, and think that if we put a leaflet through a door then people are going to come.”

She recalls starting a youth café with a micro-grant of £250. “We sat there, and the first week no one came.” They decided to persist for six months before making a call whether or not to continue. “Eight years on, and it’s still going. Sometimes, they get 12. It’s not about getting huge numbers. . . Stuff will fail, but the world won’t end.” The reworked LYCIG manual notes that not everyone was persuaded by Jesus. “We are just told to scatter seeds, and some will grow and some won’t.”

THE chief executive of the Clergy Support Trust, the Revd Ben Cahill-Nicholls, took on the house-for-duty position at Tilford Parish Church, in village in the Bourne Benefice in the diocese of Oxford, last year.

“My view of change is that, quite often, the secrets are in what already exists,” he says. “We’ve tried to build from the good rather than starting from the assumption that everything happening is bad and ripe for change.”

The parish, which had had no incumbent for two years by the time that he arrived, is a “middle-of-the-road, gently Catholic, traditional English village church”. Its ten-o’clock Sunday congregation, which numbered about 15, has grown to about 50, and the “vast majority” of the growth has come from young families. The worshipping community — including everyone who worships at least monthly — is at least twice this figure.

The tradition remains the same, and the service pattern has not changed “dramatically”, he says. “We have not reinvented the wheel. A robed choir and children’s servers team is being reintroduced, and, once a month, the Sunday-morning service is contemporary, with a small worship band — something that was already in place but has now a more liturgical structure.”

Today, the attendance has “smoothed” across the month so that some of the families that would attend only this service are now coming on other Sundays, and some of the people who avoided the contemporary service no longer do so.

Mr Cahill-Nicholls has tried to be “very pragmatic” about such patterns of attendance, he says. A small number of the congregation will still not attend the monthly contemporary service, and he tells them this is “absolutely fine”. An eight-o’clock traditional service is still available on that week.

But he has also encouraged people “to think about how they might encounter the divine”, including those families who attended only the contemporary service. “I will absolutely die on the hill that family-friendly worship does not need to be contemporary worship. . . Children love the mystery of sacramental worship.”

On the first Sunday of the month, there is an “all-age approach”. The children’s area has been moved to the front of the church so that they can “see the cool stuff”. On the other Sundays, there is a Sunday school.

“Set pieces”, such as a “blessing of the backpacks” service (Features, 10 January), have had large attendances, he says. Most of the 49 children and 65 adults at that service did not return the following Sunday, but “I would rather they come three times a year than no times a year.” It is God’s job to bring people to God, he says. “I can show them that God is loving and good.”

“What all of that boils down to is compromise,” he says. “The journey that we have been on is one of trying to meet in the middle, but also really brutally acknowledging the fact that, if we don’t welcome children and families into church on a regular basis, we are over, because a ten-person congregation is not sustainable. What I’ve found most moving has been the generosity of spirit from all sides.”

He was recently moved to tears watching an older member of his congregation, who had been most averse to change, respond to a child who had wandered to the front of the church as he began his reading. “He looked down at her with absolute tenderness and gentleness in his eyes, and said ‘Hello, my dear,’ and did the whole reading with her standing next to him, staring up at him. . . For both of them, that required give and take.”