FOR four-and-a-half centuries, the Hidden Christians in Japan lived in the shadows. To meet them, I had to go there, too: down the archipelago’s back roads, past the neon metropolises, into a landscape where history lingers like mist over rice fields.

The journey felt like a pilgrimage. Four hours by bullet-train west from Tokyo, six more by local rail, taxi, and bus, and at last I was crossing the bridge to Ikitsuki Island. The land rose dark and forbidding, its mountains wrapped in low clouds, the East China Sea boiling at its feet like a witch’s cauldron.

By morning, the storm had gone, leaving the paddy fields glistening under washed skies. There I met Masaishi, a 75-year-old farmer, his face lined and bronzed from a lifetime in the fields. He lowered his voice, as if secrecy were still required. “There are only a few of us left, my friend,” he said. “We’re the last generation.” Then, almost shyly, he hummed a chant. The notes, low and insistent, seemed to drift across the centuries — echoes of prayers that the first Jesuit missionaries might have heard when they landed in 1549.

THE arrival of Christianity in Japan was sudden and electrifying. St Francis Xavier and his companions stepped into a feudal society bound by rigid hierarchy: peasants tied to their plots; samurai enforcing the shogun’s decrees with the edge of a blade. The missionaries offered something unheard of: dignity. They treated the poor with kindness and preached equality before God. Whole fishing villages and farming communities embraced baptism. Within a generation, hundreds of thousands had converted.

But the faith spread too far, too fast. Alarmed, Samurai rulers in Japan suspected that Christianity was the advance guard of Iberian conquest. In 1614, they expelled the missionaries and outlawed the religion. What followed was two centuries of relentless persecution. Converts were crucified or beheaded; some were boiled alive in Nagasaki’s sulphur springs. Torture chambers were devised specifically to break Christian prisoners. The message was stark: recant or die.

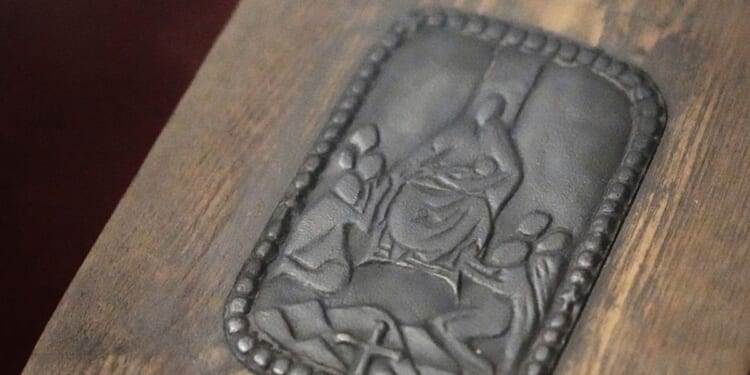

YET faith found ways to endure. Believers re-carved statues of Mary to resemble Buddhist figures. Prayers were disguised as sutras. Families registered at temples while secretly baptising their children at home. Crosses disappeared; stories of the saints were retold as folk tales.

They came to be called Kakure Kirishitan — Hidden Christians. For 250 years, entire communities preserved fragments of Catholic liturgy without ever seeing a priest. They baptised, they prayed, they whispered the gospel in words no longer fully understood, but still alive.

When the ban was finally lifted, in 1873, many rejoined the Roman Catholic Church. Others, like Masaishi’s ancestors, remained apart, convinced that they were the keepers of the true, unbroken faith.

TODAY, that faith is fading. Scholars believe that only a few hundred Hidden Christians remain, down from a few thousand just a generation ago. “My sons aren’t interested,” Masaishi told me with a shrug that did not hide his sadness. “Young people leave the island anyway. We are the last of the few.”

The landscape still bears the scars. On Hirado Island stands the shrine of Danjiku-sama, where, in the 17th century, a family was hunted down: Yaichibei, his wife, Mary, and their young son, John. They hid in a bamboo thicket, but the boy strayed to the beach and was spotted. All three were captured and beheaded.

To reach their memorial today, you descend a slippery zigzag of stone steps, the waves thundering louder with each turn. It is impossible not to imagine those as the last sounds that the family heard. Every year, on 16 January, villagers gather there to remember them.

THE RC Archbishop of Tokyo, the Most Revd Tarcisius Isao Kikuchi, acknowledges the paradox. “They are clearly Christians,” he told me. “Their cultural heritage should be preserved. But their numbers are so small I fear their sect may soon die out.”

The Vatican praises their endurance, but their rituals — Christian faith blended with Buddhist form — make them theological outsiders. With no hierarchy and little adaptation to modern Japan’s secular drift, the Hidden Christians are close to extinction. And yet, faith does not always vanish. Sometimes it transforms.

At the bus station in Hirado, I met Ryo Satamurum, a 40-year-old civil servant. His late great-grandfather, Kanematsu Nagata, had been a Hidden Christian. Mr Satamurum’s pride in him was palpable. “He was a man of true faith,” he said, “very Japanese in his Christianity. He gave us strength. He inspired my grandfather, my father, and me. Because of him, our family joined the Catholic Church.”

From his wallet, Mr Satamurum produced a photograph dated 1927. It showed Kanematsu, solemn, unsmiling, his gaze steady. For his descendants, his faith was not a relic, but a foundation.

TODAY, Hidden Christian sites in southern Japan are inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage list. Yet, on Ikitsuki itself, fields go untended, schools stand half-empty, and young people drift away. On paper, survival seems impossible. But survival, improbably, is the Hidden Christians’ story. Even if the chants fall silent, their memory will endure — in photographs, in shrines, in families like Mr Satamurum’s, who carry their faith into another form.

As I left Ikitsuki, storm clouds gathered again over the East China Sea. The cliffs stood, as they have done for centuries, battered and yet unbroken. I thought of Masaishi’s whisper, his chant, his sorrow at being the last; and of Kanematsu’s photograph, passed like a relic through the generations. Between them lies the paradox of the Hidden Christians: a faith at once vanishing and eternal, fragile as breath, enduring as memory.

John Cookson is a freelance television correspondent and author.