I WORKED as a BBC producer for 22 years — first in radio, then mostly on the Everyman documentary series. I also spent a year with the Horizon science series.

I loved my job, and thought myself incredibly fortunate to be able to travel the world, meet extraordinary people in public life, and try through my efforts to produce programmes that could open new windows on the world for listeners and viewers.

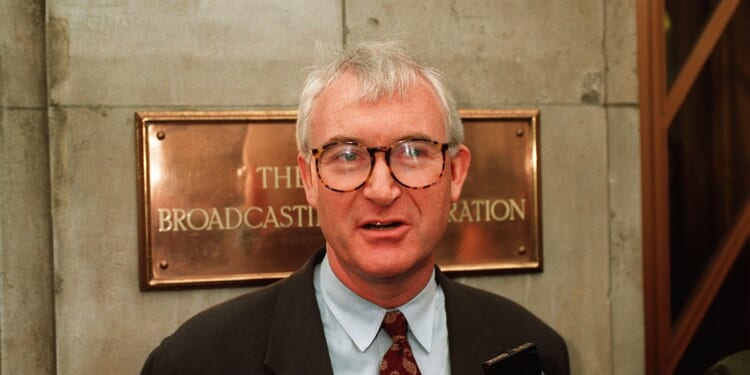

Everything changed when John Birt was appointed Director-General in 1992. He quickly made it clear that the producer’s job was to sit in the office researching a subject, writing a virtual script, and then going out to film more or less exactly to order. As the broadcaster and journalist Dr Graham Majin has explained in a recent edition of the online journal Quillette, Lord Birt had no time for what he regarded as old-fashioned journalism, with its attempt to establish facts, based on answers to the basic questions who, what, when, where, and how.

The new journalism was more about the why of the narrative, conforming the reporting of events to the expectations of the audience. As a senior colleague once explained to me, the producer’s job was now not so much to open a window as to hold up a mirror. Curiosity was no longer encouraged. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that I no longer fitted in the world of television documentaries, which was one reason that I began to listen to a call to ordained ministry which had been lurking about in my mind for years.

Fast forward to today’s dilemmas for the BBC, and you can see one reason that the Corporation faces its current crisis. It seems, to many, to have got stuck in a liberal/progressive narrative, perhaps appropriate in the decades before and after the millennium, but which large parts of its audiences no longer share, if they ever did, and they now have plenty of alternatives with no pretence at impartiality.

Of recent contentious issues: the editing of President Trump’s speech, the reporting on Gaza, and in-house trans-activists’ censoring of critical content, the last two I regard as having contained, or given rise to, some serious lapses in impartiality. It was shocking that Jenni Murray decided to resign after being, in her words, “cancelled” for her gender-critical views. It was appalling that the Arabic service used as a commentator Samer Elzaenen, who had called for Jews to be burned “as Hitler did”.

As for the first, which seems to have created the most fuss, I cannot believe that editing made President Trump’s speech any more provocative than it actually was. Surely we all saw the footage of the march on the White House and the mayhem that followed? I cannot forget the American film crew who asked me, before an interview: “Are we lighting this guy ‘for’ or ‘against’’? The BBC is not perfect, but it is better than most. Who, what, when, where, and how: facts do matter.