THIS exhibition introduces us to the stone workers, potters, glass- and faience- makers, metalworkers, jewellers, woodworkers, those who grew and prepared papyrus, joiners, and coffin-makers working in Egypt up until the reign of Cleopatra. We not only see how skilfully they operated, but we meet individuals.

In the first room, there is the richly coloured cartonnage mummy-case of a fellow priest, Nakhtefmut, buried about 892 BC, which was presented to the museum in 1896. His duties combined that of priest and of sacristan, opening the shrine of the god daily, as I do the parish church.

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of CambridgeCartonnage mummy-case of a priest called Nakhtefmut (924-889 BCE), cartonnage (linen and paste), wood, gold, paint, and glass

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of CambridgeCartonnage mummy-case of a priest called Nakhtefmut (924-889 BCE), cartonnage (linen and paste), wood, gold, paint, and glass

His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had each been “Opener of the two gates of heaven in Karnak” before him. Set within a gilded face, two inlaid white glass eyes, the pupils painted on them, with black eyeliner applied, stare out at us. The body is sheathed in a rich array of gold, red earth, Egyptian blue, orpiment, green, yellow, and carbon black.

The later coffin case of Pakepu (c.684-660BC), which was shown outside its usual glass case in May 2019, is less sophisticated. There is a degree of naïvety in the painting, which is not as skilful as the carpenter’s work. Pakepu was a “water-pourer” of the west of Thebes. It would have been his responsibility, as overseer of burials, to find a suitable place for interments and then to maintain the funerary cult of the dead on the family’s behalf.

Among the astounding glass artefacts here is the famed moulded bottle in the shape of a bunch of grapes, crafted in the XIXth Dynasty, 1295-1069 BC, which is when many think Moses led his people to freedom. The neck of the ointment pot has coloured bands of yellow, black, and white, with a lip of aquamarine.

Here we are invited to marvel at a woman’s hand-written complaint that she could not get the staff. Ir was a supervisor in a weaving co-operative outside Cairo at Lahun (in the XIIIth Dynasty, some time between 1976 and 1793 BC: the catalogue and exhibition make no mention of Dynasties, which puzzled me). She explained that her girls simply could not weave.

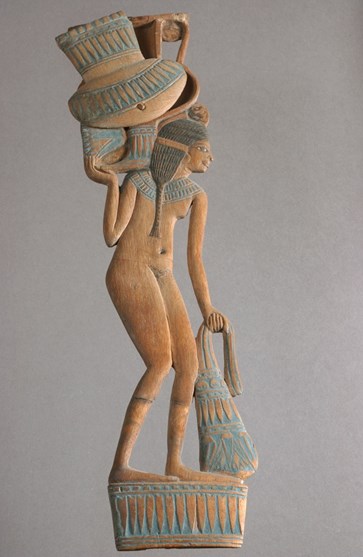

© Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn. Photo Christian Décamps

© Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn. Photo Christian Décamps

Decorative spoon with an elaborate handle and swivel lid (1327-1186 BCE), wood (carob and tamarisk) and paint

She wrote in a cursive hieratic script rather than in hieroglyphs, as did the stonemason who signed the side of the shrine that the 15th-century BC Thutmosis III ordered for one of his temples: “the outline draughtsman . . . made it.” Sadly, his name has been erased.

There is much writing in this exhibition, and sketching. A grid drawn in the Saite period on limestone in the XXVIth Dynasty (664-332 BC) offered a stonemason a template to cut a bas-relief of a wild cat, a sphinx, and a gazelle. From the end of that dynasty comes a model sphinx (Berlin) with incised lines to allow it to be transferred to a much larger piece of sculpture.

According to the inscription on a grave stela, Ripa and his son Pabau were cobblers by appointment to His Majesty in the XXth Dynasty (1189-1077 BC) (Berlin), providing their king with sandals. More than 800 years before (c.1976 BC), Amenemhat had been celebrated as a carpenter (Louvre). Two brothers, his “sister” (perhaps meaning wife), his mother-in-law, and several other family members are recorded, which suggests that the family all worked in the joinery company.

As a man in a hurry, or perhaps a hard-pressed factotum, in the XIXth Dynasty, Nakhtamun, wrote to order overnight delivery of four bespoke wooden windows, the design for which is then drawn: “It is a job to do four of this type exactly. Exactly! But hurry, hurry, by tomorrow.”

A word of warning; pens and pencils are not allowed in the gallery, which seems a pity if it puts off visitors from sketching or taking notes in what is, after all, a university collection in a publicly funded museum.

“Made in Ancient Egypt” is at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, until 12 April 2026. Phone 01223 332 900. www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk