ANGLICANS working for peace and reconciliation in widely different contexts around the Communion have been reflecting on how to overcome divisions and build unity. This was the focus of the last of ten webinars exploring how the Lambeth Calls — commitments made on key themes at the 2022 Lambeth Conference — can be taken forward.

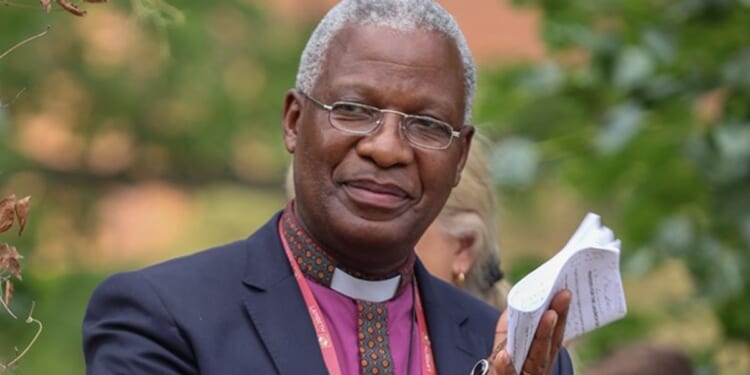

Panellists included the Archbishop of Cape Town, Dr Thabo Makgoba. “The world’s wounds are real, and we must own them,” he said. “We recognise that those who are generally comfortable with the status quo have sometimes promoted what, in South Africa, we call cheap reconciliation, aimed at papering over cracks in the hope they can maintain their status.

“To achieve peace, we need justice, and that means confronting the self-serving elites in all those countries, rich and poor, who wield economic and political power for their own benefit.”

He spoke of the work of the Anglican-led global centre for reconciliation, based in Cape Town, and particularly of the growing scramble for the world’s mineral resources, “often located in countries that have a weaker governance, with Indigenous people and marginalised communities who are unable to fend for themselves when the government leaves them without any recourse”.

“Courageous conversations” in South Africa had brought together in one room “powerful mining CEOs who thought they could do as they pleased”, trade-union leaders, and leaders from mining communities, he said.

“We create a safe space, and we talk about the reality of the impact of mining. It’s a give-and-take, because, if you hit hard, they will hit harder, and then the whole process of reconciliation will be gone.”

The Barbados-born First Church Estates Commissioner, Alan Smith, reflected that reconciliation was a personal and professional journey, indivisible from seeking justice and standing firm against violence.

His identity was Black Afro-Caribbean British, “yet when we dig more deeply, on my father’s side, I have descended from black African enslaved and white English persons,” he said. “On my mother’s side, I have Portuguese heritage, and also ancestors from India, who travelled to Trinidad as indentured servants.

“My Smith surname comes from the plantation overseer who had a fleeting relationship with my teenaged paternal great-grandmother, Rebecca. . . Yet, paradoxically, that Smith name has afforded me greater safety in the world of England. It is the character of my great-grandmother, and the dignity and agency of her work in her entire life as a cook, that has resulted in me being able to speak to you today.”

Reconciliation was not theoretical, but came alive in daily work, he said. “Our historical links to transatlantic chattel slaves is at the core of reconciliation. It has left lasting legacies and mindsets that still [lead to] unjust outcomes and violence, perhaps more psychological than physical, but yet equally pernicious.

“Our journey as Christians is about emancipation from enslavement of all types, of the breaking of chains when we embark on such journeys of reconciliation. Tough as they are, they start the process of healing.”

Larissa Minniecon, a community support worker with Indigenous people in Australia, said that, unless the Church maintained its prophetic voice and spoke against injustice, the Government would never change.

“As Indigenous Christians, we want to stand in the position of truth telling, and the Church and communities need to learn the discipline of truth-listening. Here in Australia, the idea of reconciliation was actually born out of high incarceration rates and deaths in custody of Indigenous people.

“So, in my country, it looks like laws that stole our children; it looks like Australia being the only country in the world that still imprisons children as young as ten; it looks like the rising number of single-parent households. . . It looks like ongoing trauma and Indigenous people struggling to find healing and hope, and it looks like fighting for land rights, climate change, and creating justice.

“And, in the middle of all of this,” she continued, “we ask the simple and confronting question: where is the Church? Is this not our mandate, to save, to nurture, to heal the brokenness of the world? In Australia, reconciliation has been shaped more by our government programmes than by the Church. When identity, spirituality, and sacred responsibilities are separated into government boxes, true reconciliation becomes impossible.”

Agnes Lam, a member of the Anglican Communion Youth Network, praised the Difference course developed by the Reconciling Leaders Network at Lambeth Palace. “Listening to and understanding others sounds very simple,” she said, “but, when we really try to practise that in our daily life, it becomes a lot of struggle, and we can see different emotional hindrances that hold us back from really practising reconciliation; so it’s a mindset change. I found the course a very useful tool for everyone, not just for the teenagers.”

Describing Hong Kong as “a highly pressurised city”, she recalled a time of social unrest when the entire society was in “a very dark period, where everybody was pointing fingers towards different parties. . . The young people especially felt very hopeless, because we could not see the future that we were going to hold, or the society that we were going to lead. We felt we needed a space where we were cared for.”

The Church had initiated an ad-hoc conversation, she said: “a moment just for us to share all our burdens, a time when I realised it was also playing a huge role in really promoting reconciliation. . . I urge young people, if you take the Difference course, you will feel the change in mindset. The forgiveness that we hold for others will become easier.”

The Vicar of Christ Church, Nazareth, the Revd Nael Abu Rahmoun, reflecting on his own identity as Arab, Palestinian, Christian, and Israeli, said: “I like this complicated identity because I share some part of every category with different people. I find hope in that for a better situation and a better relationship.

“Everybody knows the Holy Land is a territory which has historically suffered with injustice, conflicts, and war, and we continue to suffer. We continue to face difficulties and challenges. Reconciliation is part of our daily life, of every ministry that we do, and it’s more than ever necessary that we need to understand the concept and try to live it.

“The loss of trust between governments, groups of people, and nations is a problem, and the process of building it has almost disappeared in these days. But we have to put all our efforts together to do that. Rebuilding this trust [will involve] gathering people together, finding more partners, people of different religions and faith.”

He expressed a longing for the end of occupation, describing it as “the original sin”. Talking about peace was good, he said, but it was not enough. “It’s time to act, it’s time to to be peace-builders. . . Let us continually ask ourselves how can we can each contribute to the peace process in our own communities, in our own neighbourhoods, but also in the churches.”

The Christian hope offered by the resurrection was not “some nebulous, pie-in-the-sky concept”, he said. “It is, rather, the driving force which motivates me in my determination to name the problem, to identify the solutions, and then to mobilise people to overcome those challenges.”