THE English word “Advent” sets the theme of the season, coming from the Latin adventus, meaning arrival. It is the period in which Christians reflect on Christ’s coming — or, rather, his comings, since we combine preparation for Christmas with making ready for the end of all things.

We call Christ’s second coming the Parousia, a Greek word meaning “arrival” or “presence”, corresponding to adventus in Latin. It was used especially for an arrival in person, such as a royal visit. Another seasonal Greek word is maranatha, meaning “Come, Lord!” or “Our Lord has come!” (1 Corinthians 16.22).

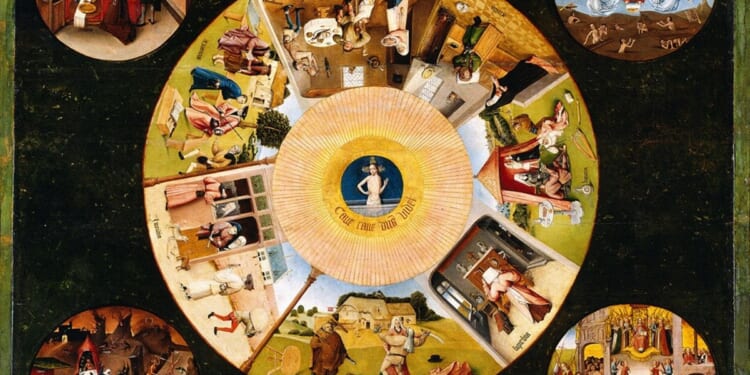

THE Four Last Things have traditionally provided subject matter of sermons on the Sundays of Advent. The first — death — has little to offer in terms of etymology, since words with that sound have shared that meaning into the mists of linguistic time. The thing has not changed (the two constants in human life being, as Benjamin Franklin observed, “death and taxes”); so neither has the sound of the word.

Scholars do note, though, how often and creatively people come up with euphemisms for death: “to kick the bucket”, “to pass”, and so on. On the one hand, then, the word “death” remains static; on the other, we are endlessly inventing new ways to talk about it obliquely.

The second last thing is judgement. The word goes back to the Latin ius (law), giving us iudex, a judge (from ius + dicere: one who speaks the law). In Advent, we are not so concerned with law (ius) as an abstraction as with the one who sits in judgement (Christ as judge).

A 20th-century trend in theology, associated with Karl Barth, which sought to recover a sense of God’s judgement, was known as “crisis theology”. “Crisis” derives from the Greek krino, meaning to judge, investigate, or separate (as in John 3.19). In English, it originally had a medical sense, as the decisive moment or turning point in the course of a disease (following ancient physicians, such as Hippocrates and Galen).

Heaven is the third last thing. The origins of the word have a physical cast to them, probably meaning “covering”: the heavens are what cover the earth. The related word “paradise” is fascinating, deriving from an ancient Persian term that entered the Greek of New Testament times as paradeisos. It had originally meant an enclosure, such as an enclosed park, and is found in Luke 23.43: “today you will be with me in paradise” (as also in Revelation 2.7).

The Old Persian (pairi-daeza) was something enclosed by a clay wall, from pairi (like “peri” in “periscope”), and a word deriving from something like dheigh (to knead clay). From this we also get “dough”, and, by an unexpected path, the English word “lady”: originally, one who kneads bread (hl?fdige, “loaf-kneader”).

The origins of the word “hell”, the fourth last thing, are again strikingly physical. As the unseen place, it derives from the primitive stem kel, from which we also get “cellar”. “Hades” is formed by the negation of the Greek idein (that which is seen), being therefore “not seen”.

TURNING to some words beyond the Four Last Things, “tribulation” comes from the Latin for “to press or extract” (tribulare). It conjures up the biblical image of the wine press (Isaiah 63.2-3; Lamentations 1.15; Revelation 14.19-20, 19.15). It may also be associated with some words of John the Baptist in Matthew 3.12: “His winnowing-fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing-floor and will gather his wheat into the granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire.”

Before you can winnow chaff from grain, you have to detach them from each other by pressing and rending the head of each stalk. For that, you run over the sheaves with a rough, heavy threshing sledge. In Latin, this is a tribulum. So, the root for our word “tribulation” is obliquely present in John’s saying, in his reference to the “threshing-floor” and how it is used.

“Purgatory”, another eschatological word, derives from purgare (from purus + agere, “to make pure”), denoting a place and process of cleansing (1 Corinthians 3.11–15; Ephesians 5.27).

Our word “mercy” points to compassion, but its roots lie in what might seem like the other direction: in “reward”, from the Latin mercedem (wages, recompense, reward), as in “market” and “merchant”. By the mercy of God, we first do not receive what we deserve (justification). Then, by the further grace or mercy of sanctification, we come so to bear the righteousness of Christ as to be able justly to share his reward.

That word “reward” relates to someone who has been noticed and cared for (or, perhaps, to someone who notices and cares for another). The “ward” part of the word shows up when we speak of a child who is “kept in ward” or a “ward of court”.

WORDS to do with ending and reckoning are much in mind during Advent. “Fate” has religious roots, from the Latin fari, “to speak”. From it comes fatum: “that which has been spoken” — whether by gods or oracles. Alongside it stands “destiny”, as that which has been firmly appointed, from destinare (“to set fast”).

The dark English word “doom” derives from a Old English word, dom, meaning law, judgment, or condemnation. Even sterner is “wrath” from a bleak Old English word sounding much like that (wrað — angry, fierce, cruel, hostile). It evokes the sense of being twisted by anger, as in “wreath” and “writhe”. This is why Julian of Norwich wrote that “God is that goodness that may not be wroth; for God is nothing but goodness”: the divine nature cannot be twisted out of shape.

Finally, “end” (ende in Old English, and back into Proto-Germanic) meant a limit or boundary in a temporal or spatial sense, but this has expanded to take in a sense of purpose or achievement, like the Greek telos. God — the Christian end — is more consummation than conclusion.

The Revd Dr Andrew Davison is Regius Professor of Divinity in the University of Oxford and a Canon Residentiary of Christ Church, Oxford.