THE film The Carpenter’s Son (Cert. 15) owes its inspiration to the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, a second-century apocryphal depiction of Jesus’s boyhood. Scholars widely consider it unhistorical and, from St Irenaeus onwards, it was deemed heretical. Yet the film’s introductory credits imply a status similar to that of the canonical Gospels.

The film serves as a prequel (like The Young Messiah, 2016) to all those biblical epics that, like the canonical scriptures, say little about Jesus’s youth. Relying on this later Gnostic-inflected version makes for a fanciful narrative. While we do get examples of Jesus’s utter goodness, there are contrary instances, as when Jesus, called the Boy (Noah Jupe), becomes a peeping Tom, watching a naked woman bathing. Elsewhere, he kills somebody. These examples, uncharacteristic of the adult Christ portrayed in the New Testament, serve as forerunners to a climactic finale of horror.

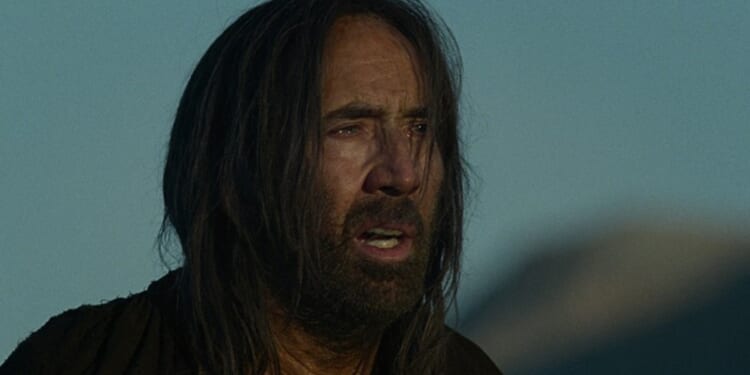

In reality, the star is Nicolas Cage, in a scenery-chewing portrayal of Joseph, called the Carpenter. He hastens the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt, but not before we have witnessed dreadful scenes of Herod’s soldiers burning babies alive. Once settled in a new country, we are presented with a dark view of this Nazarene carpenter, a controlling personality who is forever punishing Jesus for something, and eventually casts him out altogether.

As for Jesus, Satan (absent from the Thomas account) mysteriously comes in the guise of a companion: something of a fallen angel taking revenge against God by trying to corrupt his only-begotten son. Satan’s enticement of Jesus into temptation means that Jesus encounters demonic images of evil, and these provide the film with an opportunity to display many of the usual tropes of a horror film. The director Lofty Nathan’s rationale for this stems from his upbringing in the Coptic Orthodox Church. He says that his film is asking what it would have meant to live in a time before science, before the age of reason, when every moment carried the weight of unseen spiritual forces.

This is to suggest that rationality did not exist in antiquity and thereby ignore the immense contributions, Christian or other, to human thought at that time. Invisible spiritual phenomena do not suddenly disappear after the dawn of the Age of Reason. Most horror movies are, indeed, set in more recent times.

The Carpenter’s Son is more fright flick than biopic, but, nevertheless, we should avoid blanket dismissal of horror films in general. The genre has a respected cinematic pedigree. Throughout the centuries, Christian art has wrestled with the powers of evil and the hope of deliverance; and film has, too. Here, Joseph’s black moods bring us closer to understanding our own and where they could lead us. What Jesus envisages when tempted by the devil allows us to give flight to our own imaginations. There are horror enthusiasts who argue that such moments, which put the fear of God into us, are transcendental, leading to reverence for a higher power. The Carpenter’s Son probably falls a little short of that.