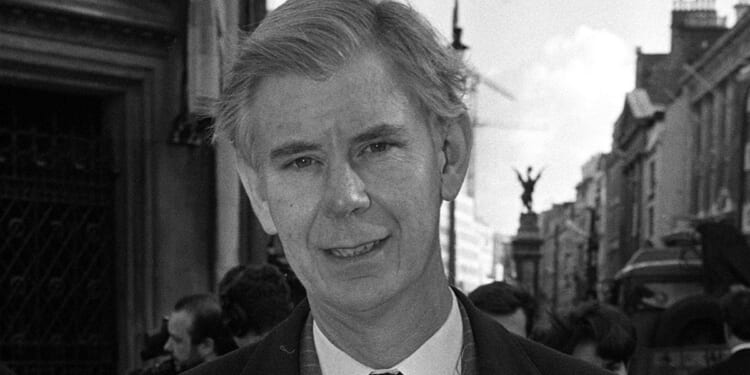

YOU don’t found a newspaper without ambition, and Sir Andreas Whittam Smith was a determined man who hated to lose. The other two founders of The Independent were the scions of privilege: Matthew Symonds, the son of a Labour peer, and Stephen Glover, who managed to give the impression that everything in his life would be rather a comedown after the editorship of the Oxford student magazine Isis.

Andreas, even though he reached the heart of the Establishment, never lost a certain gawky provincial rectitude and with it a shrewdness about human failings, his own and other people’s. He valued hard work and honesty, and told me once that he kept up to date a list of his own eight greatest mistakes.

Although he hired me as the paper’s religious-affairs correspondent a few months before the paper was first published, I never felt then that I knew him; perhaps this was because he went on to promote me to and sack me from several other jobs.

Decades later, we started to have intermittent lunches while he was at the Church Commissioners and after his retirement. He surmounted whatever disappointment he had felt at my failure to live up to the promise that he had once seen, and talked with remarkable candour and insight about his own struggles; unusually for journalists reminiscing, he talked very little about other people’s failures.

The paper that he edited was an extraordinary achievement. I used to run up the stairs out of Old Street tube in my eagerness to get to work there in the mornings. He managed to make the journalists feel that they were writing for intelligent grown-ups. “We want to be the paper that the permanent under-secretaries read on their way to work,” the science editor once said. “We want to be what The Times would be if it were still a real paper,” said the exiles from Rupert Murdoch’s Wapping. Andreas spoke disparagingly of “the fascist thugs on the back bench” at The Daily Telegraph. He was on our side.

Decisions were quickly made and immediately acted on. The spacious design and the glorious use of photographs both emerged, unplanned, from the months of dummies immediately preceding the launch. When we launched a God-slot, it took three days from the first proposal to the first article appearing on a redesigned printed page. The corresponding process at The Guardian, 20 years later, took six months to produce a web page.

It is easy to forget that, in the first winter of The Independent, the circulation headed steadily downwards as the novelty of its existence wore off. A faction on the board conspired to replace him and take the paper downmarket. He fought them off, and his vision of independence was justified by the 1987 General Election campaign, which gave a lasting boost to the paper’s sales. But the experience marked him, and led him to his greatest mistake. By 1990, the paper was thriving, but there were persistent rumours that Robert Maxwell wished to buy it.

It was to avert that possibility that Whittam Smith spent £20 million on The Independent on Sunday, which was launched into the recession that drove Maxwell to suicide. The effect on The Independent was less dramatic, but, after a few years, it ended entirely the paper’s independence and its original character.

Whittam Smith bore his dethronement with courage and dignity, but it must have been a great shock to start work at the Commissioners. It was the best way in which he could serve the Church. “You’ve always been better at spotting a crook than a heretic,” I told him once, and he agreed. But a newspaper editor is an absolute monarch, no matter how republican his principles. The First Church Estates Commissioner is not. Whittam Smith told the BBC that “You’re in the driving seat of a car with apparently a steering wheel and apparently an accelerator and apparently a brake, but when you turn the wheel or press the pedals nothing much happens. That’s the nature of it.”

At the Commissioners, he foresaw and largely avoided the great crash of 2008; later on, he was enthusiastic about the Welby/HTB plans for resource churches: “You have to have business-getters,” he said once, rather shocking me, since that’s not how I think of the clergy.

But, at the same time, he expected most of these experiments to fail, and would have dealt with the failures ruthlessly, valuing only the lessons that could be learned from them. His own spirituality, he said, was formed by the Prayer Book and the Church that has now disappeared. In later life, he would listen to Roman Catholic services broadcast from Paris as a substitute for matins. When I think of him now, it is largely his kindness that I remember. He’ll be memorialised for other achievements, but, most importantly, he was and remained a good man.

Read our obituary of Sir Andreas Whittam Smith here.