IT BEGAN with a war and a woman.

After the horrors of the Second World War, with its endless capacity to kill and maim, uproot and bereave, impoverish and disillusion, came a wave of idealism determined to build not just “a land fit for heroes”, but a world fit for all humanity where such horrors would be no more.

Those were the days of the Bretton Woods agreement, signed in 1944 by 44 nations, establishing international rules for trade and managing money. It gave birth to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB), both designed to foster a healthy and fairer world economy. They were followed in 1945 by the transformation of the League of Nations into the United Nations, designed to keep the peace.

At the national level in Britain, one sign of this idealism was the Beveridge report of 1942, a blueprint for social policy in post-war Britain, which, championed by determined politicians such as Aneurin Bevan, heralded the formation of the welfare state.

But the aftermath of those horrors remained, and compassion could not turn a blind eye. In Europe alone, 40 million people had been displaced, 11 million of them in Allied-occupied Germany. They included survivors of concentration camps and prisoners of war. They were known as displaced persons (DPs), and were not always welcome when they tried, or were forced, to resettle back home.

Six million had been deported from Ukraine, Poland, France, Italy, Latvia, Belarus, Russia, and Yugoslavia, and forced to work in agriculture and industry in Germany or its occupied territories, so fuelling the war that caused their suffering. Now it was over, and they were stranded.

Working among them was a middle-aged woman characterised as “formidable” and “autocratic”, but essentially “deeply compassionate” and good company, who “without being tall . . . confronted others as being a tower of strength” (as described by the prominent British educator Eric James). Employed at the time by the YWCA and then YMCA as education secretary, Janet Lacey was working on social projects that brought together soldiers from the British Army of the Rhine, now being demobbed, with young German soldiers and refugees.

She experienced something of the devastation and misery of post-war Europe, bad enough in the West and even worse in the East. She was also in contact with the international ecumenical movement, the nascent World Council of Churches (WCC), and church leaders such as George Bell.

Once back in Britain, Lacey was appointed youth secretary of the British Council of Churches (BCC) in 1947. In 1952, she became secretary, and later director, of its faltering Inter-Church Aid and Refugee department. In 1957, during the second week of May, she organised the first Christian Aid Week. She renamed her department “Christian Aid” in 1964.

By the time she left, in 1968, more than 400 churches and committees were involved. Together, they were raising £2.5 million (£42.5 million in today’s money) per year to fund development projects in 40 countries.

LACEY was born in Sunderland, the daughter of a Methodist minister. On his death, she moved to live with her aunt, in Durham, where she saw something of the harsh realities of life in the nearby mining villages. After technical school, she began her working life, training as a youth worker with the YWCA, first in Kendal and later, by 1932, in Dagenham.

She was a founder member, in 1958, of Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO). In 1959, she sat on the UK World Refugee Year committee. She chaired the WCC’s work on refugee service, and, in 1956, wrote By the Waters of Babylon, a WCC dramatic statement on the plight of exiles. An “ecumenical ballistic missile” if ever there was one, she travelled widely, including on one of the earliest jet-planes, Comet II.

Christian AidJanet Lacey, the first director of Christian Aid

Christian AidJanet Lacey, the first director of Christian Aid

After Christian Aid, she became director of the Family Welfare Association from 1969 to 1973, and, finally, reorganised the Churches’ Council for Health and Healing. She was appointed CBE in 1960, and awarded a Lambeth doctorate in 1975. She was the first woman to preach in St Paul’s Cathedral. In 1970, her autobiography, A Cup of Water, was published. A photograph of her is kept in the National Portrait Gallery.

In her youth, Lacey trained to be an actor. She performed in the mining villages of northern England, but, despite her talents as a playwright and performer, she decided not to pursue a theatrical career — although in one way, she did: she was said to bring something of the art of an impresario to her working life. In retirement, she could be visited in her basement flat, not far from Sloane Square, in London, and, appropriately enough, close to one of its most pioneering theatres, the Royal Court.

BUT, if Christian Aid began with this remarkable woman, it also began in response to an emergency in Europe, closely followed in 1948 by the flight from their homes of 700,000 Palestinian Arabs to the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and Lebanon. They fled, never to return, during a war triggered by the withdrawal of the British, and by the declaration of independence by the State of Israel.

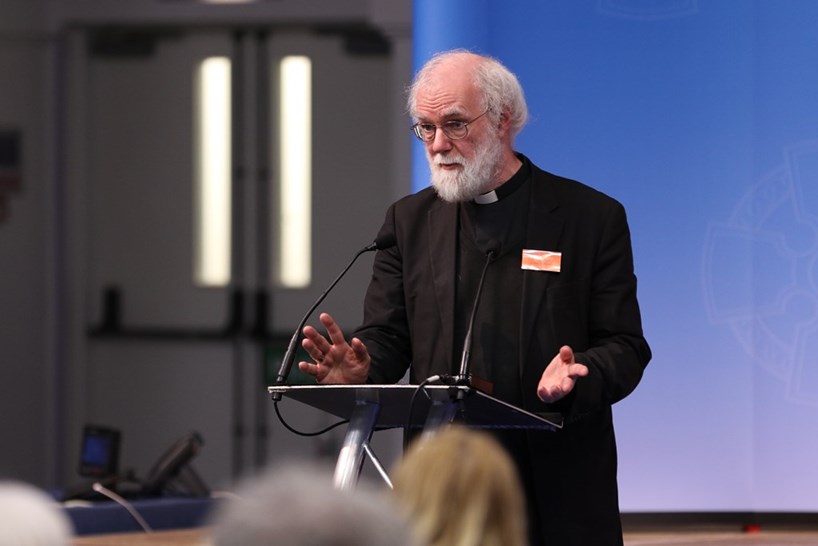

Since then have followed countless emergency appeals: Lacey spoke of 20 a year in the 1960s; Rowan Williams, then chair of Christian Aid, referred to 2015-16 as a year “full of humanitarian crises”. Christian Aid’s income could rise dramatically (in 1983-84, for example) and then go down (in 1986-87). In 1972, there were no emergency appeals, and, in 1982, no major ones.

All this required careful management — not least to ensure that supporters at home understood the fluctuations, and that humanitarian aid in all its complexity and scale did not deflect attention from longer-term work, which, according to the annual figures on expenditure, it did not.

Church in WalesLord Williams, then chair of Christian Aid, urged the Church in Wales to re-adopt the agency as its own development arm at a meeting of its Governing Body in 2016

Church in WalesLord Williams, then chair of Christian Aid, urged the Church in Wales to re-adopt the agency as its own development arm at a meeting of its Governing Body in 2016

Many appeals have been made in co-operation with the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC), founded in the early 1960s. Although the agencies had worked together in 1959-60 to make World Refugee Year a success, in the early years there had been growing competition between them. It had given rise to considerable tension, not least when Oxfam adopted quite aggressive tactics — or, as some would say, up-to-date marketing techniques, applying business methods to charitable activities.

On one occasion, Oxfam had appealed directly to the churches, and was heavily criticised by Lacey. It was Lacey who encouraged co-operation and co-ordination instead of competition. She proposed a committee with a view to making joint appeals and sharing the donations equally between its members. After informal meetings, it was set up in 1963 by the Red Cross (which provided the administration), Christian Aid, Oxfam, Save the Children, and War on Want. Later that year, it became the DEC.

The first DEC appeal was made in 1966 for victims of the earthquake in Turkey. By 2024, there had been 77 appeals, raising £2.4 billion, with a membership of 15 charities governed by their CEOs, together with independent trustees. A Rapid Response Network of national media, including television and corporates, helped to raise the alarm and set up easy ways for the public to donate. Members had to explain how they would use the money, and then do so within a strictly limited period of time, and for the stated purpose of the appeal.

After the Boxing Day tsunami in 2004, for example, Christian Aid and its in-country partners promptly reached more than half a million desperate people with food, shelter, and health care. The Church’s Auxiliary for Social Action (CASA), in India, set up feeding stations by the next day (27 December), and the National Christian Council of Sri Lanka (NCCSL) was sending food to hard-hit areas by 28 December; but it is not always easy to spend large sums of money quickly and well.

WAR, violence, disease, cyclones, droughts, earthquakes, storms, floods, and famines pay little respect to geographical boundaries. All corners of the globe, from east to west and north to south, from Haiti in the Caribbean to Eastern Europe, have found themselves in need of humanitarian aid: Africa more often than others, with Asia not far behind.

Together, their stories and Christian Aid’s story make up a tapestry of efforts to support desperate men, women, and children doing their best to survive as they lose their homes, their loved ones, safe havens, health care, schools, drinking water, the means though not the ability to feed and take care of themselves, and more.

DEAN & CHAPTER OF WESTMINSTERPlacards featuring the charity’s past campaigns are carried down the centre of the Abbey nave at Christian Aid’s 80th-birthday service in Westminster Abbey in June

DEAN & CHAPTER OF WESTMINSTERPlacards featuring the charity’s past campaigns are carried down the centre of the Abbey nave at Christian Aid’s 80th-birthday service in Westminster Abbey in June DEAN & CHAPTER OF WESTMINSTERPlacards featuring the charity’s past campaigns are carried down the centre of the Abbey nave at Christian Aid’s 80th-birthday service in Westminster Abbey in June

DEAN & CHAPTER OF WESTMINSTERPlacards featuring the charity’s past campaigns are carried down the centre of the Abbey nave at Christian Aid’s 80th-birthday service in Westminster Abbey in June

Through this tapestry of needs and responses, however, runs a thread. Although it became more explicit as time went on — and, in 2022, very explicit — right from the start Christian Aid had a bias to the local, or, as later referred to, “localisation”: a bottom-up rather than top-down approach to humanitarian aid — and, indeed, to all aspects of its work.

It was locally led. A generally non-operational approach reflects this, but it is fundamentally a matter of respect for people, and what they are well able to do for themselves; of finding out their needs from them, and what forms of support will be of most use to supplement their own resources.

Whatever that may mean, from ready money to training, it definitely does not mean outsiders’ assuming what is best for desperate people and flying it in, acting for people and not with them. When it comes to accountability, it is not only about agencies’ being accountable to funders, but whether, according to local people, they received the kind of support they needed, and, in turn, whether they made good use of it.

Of course, it is not as if no other NGOs have acted in this respectful way or that a bias to the local does not have its problems, especially when people are too exhausted to cope or are uprooted and their communities have been all but destroyed; but, whether unique or not, this bias to the local can be traced throughout Christian Aid’s story.

Some emergencies and the appeals that went with them, such as Biafra, Ethiopia, and Rwanda, stay long in the memory. Others get forgotten as the world moves on, but are no less disastrous for their victims and important to agencies like Christian Aid, which try to stand by them. It goes without saying that in every case Christian Aid appealed for funds to its supporters, many — though by no means all of them — in the churches, and was never let down.

This is an edited extract from Justice Song: The story of Christian Aid by Michael Taylor, published by SPCK at £17.99 (Church Times Bookshop £16.19); 978-0-281-09198-0.