DENSE, or quick? Or clever? Or weird? Computers come in all three varieties. The strange abilities of the third sort — with quantum computing — recall the Advent theme that Christ “will bring to light the things now hidden in darkness and will disclose the purposes of the heart” (1 Corinthians 4.5).

We have wanted computers to be more powerful ever since we started building them. In 1965, Gordon Moore (co-founder of the chipmaker Intel) predicted that the number of transistors packed on to a microchip would double about every two years. “Moore’s Law” got it about right. The structure on a chip is now so small that physics will make further progress difficult, although other tweaks keep progress going.

For a long time, computing power increased through density and speed. More recently, computers have also got clever, with artificial intelligence or machine learning. That, however, rests directly on speed and density: you can ask AI to rework the “Hokey Cokey” in the style of Seamus Heaney translating Beowulf (do look it up) only because there is such powerful hardware for it to run on.

Since “clever” computers can see patterns that we never could, they can solve problems that no previous computer could. One example involves predicting protein structures: what AI can do there is stupefying.

BUT what about “weird” computing? By that I mean the new field of quantum computing (proposed only in the 1980s), which comes into its own for problems for which classical computing offers few shortcuts. An important example involves cryptography and decoding secret communication.

The security of much of the internet depends on the practical impossibility of solving certain mathematical problems (specifically, identifying the prime factors of very large numbers). Using existing means, if you try a solution and your guess is wrong, you get no help deciding what your next guess should be, except that you have ruled out one possibility.

It’s not as though you could rule out half of all the options with one move, and half of what’s left with the next, or something like that. You cannot converge on an answer quickly, which makes this sort of mathematical problem the ideal basis for transferring information secretly. You and your trusted partner have the key; a spy has to make an impossible number of guesses. The weirdness of quantum computing could change that, however, so that what once looked impregnable now seems less secure.

Computers up to now have relied on being predictable. Every last “bit” of information is preserved pristine, for as long as you need it, 0s remaining 0s, and 1s remaining 1s.

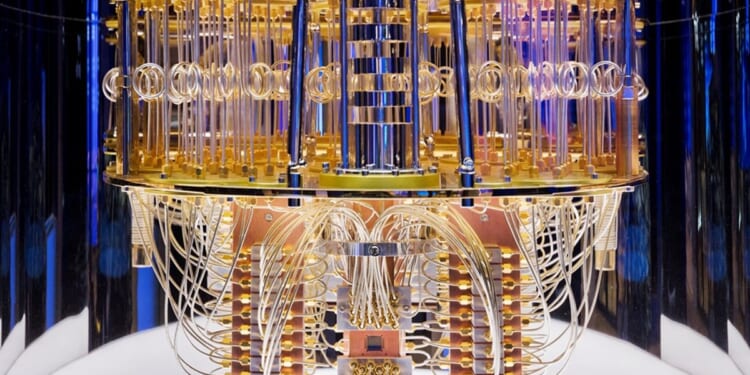

Quantum computing is different: it is built on randomness and uncertainty. Quantum computers (which are feats of engineering) use quantum states to represent numbers as “maybe this, but maybe that”. They do not represent any particular number, until you decide to check (like Schrödinger’s cat, which — as the metaphor goes — is not determinedly dead or alive until you look).

Make the fateful measurement immediately, and the quantum computer does no better than spitting out a random number. That is an idiosyncratic way to spend several million pounds, when you could just throw dice. Preserve your quantum state, however (being careful not to measure anything, to retain the strange ambiguity), and manipulate it carefully: then, when you take your measurement, you can make it likely to be the answer that you are looking for.

That can get you to your answer in far fewer steps than a standard computer could. If that would probaby take n tries or calculations to get there, one way to use a quantum computer needs only the square root of n. The harder the problem, the greater the saving, and that matters in cryptography.

Current experiments in quantum computing already anticipate this sort of work. A far more advanced kind — way beyond the bounds of current engineering — would unleash the power of this “weird computing” in an astonishing way, cracking in minutes a code that would take a conventional computer the whole age of the universe.

This has got computer scientists and cryptographers looking for new methods to keep transmissions secret. But what about past data? Stories are coming out of foreign governments’ stashing information from data breaches. They cannot decrypt it now, but hope that a fully functional quantum computer could do that in the future. “Harvest now; decrypt later.”

THIS reminded me of an Advent theme: “there is nothing hidden, except to be disclosed; nor is anything secret, except to come to light” (Mark 4.22, with parallels in Matthew 10.26-27; Luke 12.2-3). The revelation of every thought and action awaits the last judgement; the revelation of emails may come sooner.

To be honest, the prospect of that may be overblown. It requires quantum computers that can deal with large numbers, and the larger the number you’re dealing with, the harder it is to keep them stable. The most revolutionary techniques require quantum computers that still look like science fiction.

None the less, the Advent message remains: there will be a great unveiling at the end (which is what “apocalypse” means). As wise HR advice, it is good not to put anything in an email that you would not want read out loud in public.

The Christian will surely want to embrace this instinct, and to go further. There are plenty of warnings in the epistles against slander and gossip (Romans 1.29-30; 2 Corinthians 12.20; 1 Peter 2.1), and the injunction to combine truth with love (Ephesians 4.15). All that St James’s Epistle says about the tongue applies to fingers on the keyboard.

ADVENT reminds us of coming judgement, and it is a season of warnings; but at least we know that the warning and judgement come in love. If the cybersecurity threat is “Harvest now; decrypt later,” then God’s purpose is “Redeem now; harvest later.” The final harvest at the hands of angels is held off, so that Christ’s work of redemption might make us ready.

In the mean time, our lives will be happier if we bear in mind that God knows what we write, and say, and think (even if no hostile government ever manages to crack the codes). That is quite the provocation to speak and type in ways that add wheat to the final harvest, not weeds.

The Revd Dr Andrew Davison is Regius Professor of Divinity in the University of Oxford and a Canon Residentiary of Christ Church, Oxford.