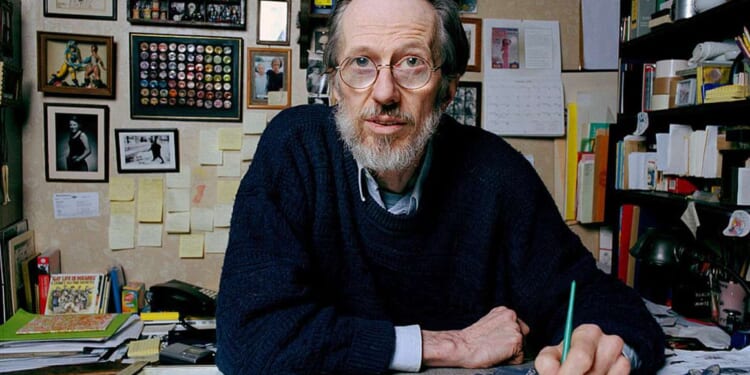

Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, by Dan Nadel, Scribner, 480 pages, $35

“In the spring of 1962, an 18-year-old Robert Crumb was beaned in the forehead by a solid glass ashtray. His mother, Bea, had hurled it at his father, Chuck, who ducked. Robert was bloodied and dazed, once again a silent and enraged witness to his family’s chaos.”

So begins Dan Nadel’s Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life. What follows is an engrossing blow-by-blow account of Robert Crumb’s peripatetic life, during which the artist almost single-handedly inspired the underground comix movement. At times, his work was called sexist, racist, and obscene, but even his critics often acknowledged that he was hilarious and original.

Crumb played a major role in inspiring and encouraging the anarchic crew of young underground press cartoonists of the mid-to-late 1960s, a group that included me. We learned to rid ourselves of internal inhibitions and external censors (including the often-fussy leftists who typically staffed the underground papers) and go for broke—sometimes literally.

I had the good fortune to meet Crumb in Chicago in the summer of 1968. He was on one of his cross-country trips, crashing on the couch of Jay Lynch, a local underground cartoonist and mutual friend. I was fresh out of high school and eager to learn the craft of cartooning.

I pored over Robert’s jam-packed sketchbook of ink drawings of goofy characters and sketches of gritty urban life. It changed my life: His bolt of inspiration fed my creative work for years to come. He had that effect on other artists too.

His childhood was often traumatic. Crumb and his four siblings were military brats, at the mercy of their Marine father’s rotation from post to post around the U.S. His parents did not get on well, to put it mildly, and their kids took solace in the world of comic books. Soon, under the tutelage of Robert’s older brother, Charles, they went beyond reading and began writing and drawing their own.

Crumb’s mother, Bea, made sure that her kids read only “funny animal” comics and similarly innocent fare. It’s easy to see how Crumb’s rebellion against his dysfunctional parents would lead to his first hit character: Fritz the Cat, a mischievous rogue perennially on the make, living a bohemian life in an urban setting populated by other anthropomorphic animals and birds.

After high school graduation, Robert moved to Cleveland where he applied for work at American Greetings. To their credit, the managers there recognized his budding talent. He took their professional skills and techniques training program; when he emerged, he was still an alienated and awkward young man, but he was one who could produce quality art with popular appeal.

In the mid-’60s, even a declining industrial center like Cleveland had an emerging counterculture. There, Robert met Dana, his soon-to-be wife. Both were barely out of high school, and what was probably puppy love turned into an awkward marriage of naifs who clung to each other, trying to make decisions about a future they could barely imagine.

After a few years of grinding out greeting cards and ingesting LSD and marijuana, Robert and Dana relocated to San Francisco in early 1967. That year, droves of would-be flower children arrived for the legendary but ill-fated “Summer of Love.” Robert made contact with local hip printers and artists while continuing to do cards for American Greetings and Fritz the Cat strips for Cavalier, a men’s magazine out of New York. His readership grew considerably.

As the underground papers declined, the locus of counter-cultural cartooning shifted to underground comic books, such as Crumb’s Zap Comix. Free artistic expression and looser pornography laws meant comix could make fun of everything, including the pretensions of the counterculture and the left, sometimes in taboo-breaking and X-rated fashion. Soon the new comix were in head shops, indie record outlets, and bookstores. Crumb stayed financially afloat with a steady flow of hits, including Big Ass Comics, Motor City Comics, XYZ Comics, and Despair.

To his everlasting chagrin, Crumb’s celebrity would attract many sleazy operators and rip-off artists. On the upside, he and Dana worked out an open-marriage arrangement, allowing both to have other lovers. But the tensions between Robert and Dana increased over time, and once he met Aline Kominsky, a cartoonist in her own right and a more suitable match, his first marriage unraveled and Robert married Aline. There followed decades of their self-satirizing comix chronicling their eccentric life together.

Of all the taboo-breaking cartoonists active in the underground comix movement, why did Crumb prove the most popular? The foremost reason, I think, is that he’s an extremely gifted draftsman. He shifted between several drawing styles, from old-timey to more realistic, depending on the story he was telling, but all of them were instantly identifiable as Crumb’s work.

Then there was Crumb’s policy of fully expressing his kinky libido and id in his comix, no matter how much flak he got from feminists or puritans. It was arguably sophomoric, but it was also entertaining and titillating. Crumb’s devotion to celebrating powerful Amazonian women, with large rumps and thick thighs, gave a name to a cultural niche-fetish—what became known as “Crumb women.”

Another factor in Crumb’s popularity was that Crumb, by temperament, adored the past (and largely despised the present). That made him a good fit for a 1960s pop culture infused with nostalgia for earlier eras. Robert and Dana arrived in a San Francisco mobbed with long-haired flower children, the girls in ankle-length granny dresses and their boyfriends sporting 1880s beards, gamblers’ vests, and cowboy boots. Folk musicians like Joan Baez were reviving traditional musical styles, and rockers like the Rolling Stones were paying homage to older country and blues. Graphic designers such as Push Pin Studios used themes and tropes from art nouveau, art deco, and even Wild West signage to create distinctive ads, book covers, posters, and more.

Crumb loved the music of the 1920s and loved newspaper comics going back to the earliest era. It may not be a coincidence that one of his most popular characters was a would-be guru and con man named Mr. Natural, who walked the city streets dressed nearly identically to the star of the first American comic strip to achieve widespread fame.

That strip was The Yellow Kid, R.F. Outcault’s comic about an Irish urchin of the Lower East Side nicknamed for his trademark yellow nightshirt. It began its run in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World in 1895 but was lured to William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal in 1896 and achieved legendary status there. New full-color web presses of the era had revolutionized printing. Newspapers competed to attract readers with lavish color supplements with top illustrators and Sunday funnies featuring smart-aleck comic strips. All this soon proved hugely popular.

Today, the humor of those early comic strips needs context. Up through the 1940s, American popular humor was dominated by stereotypes and caricatures; racial, ethnic, national, class, and sex-based differences were often juxtaposed for comic effect. This was also true of the cartoons of other countries and cultures: The other was always perceived as somewhat ridiculous.

It is purely my own hunch, and not one suggested in Nadel’s evenhanded biography, that Crumb’s glee in toying with stereotypes of men, women, races, and social groups is not an exercise in bigotry so much as an homage to an earlier time, when everyone, no matter who, was granted agency and was fair game for teasing. In any event, Crumb’s wit, talent, insight, and unflagging dedication to his own shameless vision have earned him a place in the company of American defenders of free expression.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline “Robert Crumb’s Roving Art and Life.”