Of all the popular storytelling artists striving to emulate Ayn Rand, the most significant was Steve Ditko.

Ditko, a comic book artist, is most famous for co-creating Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. Rand, in addition to writing novels that still sell hugely seven decades down the line, developed a philosophy she called Objectivism, the politics of which were highly libertarian and highly controversial.

Ditko’s commitment to Rand’s ideas led him down a curious and troubled path, and made him resemble a real-life Rand character. From developing enduring legends for Marvel Comics in the 1960s to Kickstartering in the 2010s with fewer than 150 sponsors his uniquely and often bizarrely abstract stories, Ditko emulated aspects of both of Rand’s most prominent fictional protagonists.

Like Howard Roark, the individualist architect of The Fountainhead, Ditko insisted on doing the creative work his soul demanded, expressing his deepest self and values, even if few customers or patrons appreciated it. Like John Galt, the scientific wizard who led the strike in Atlas Shrugged, he was willing to walk away from his greatest inventions when he thought they’d fallen into hands that no longer deserved his best efforts.

Ditko’s most enduring impact on comics has embedded in it a personal irony. Spider-Man, created with writer/editor Stan Lee (who milked far more public relations mileage out of his role at Marvel), is credited with pioneering the idea of a superhero with feet of clay and everyday human problems, haunted by self-doubt. Ditko was contemptuous of that perceived quality, writing that “Lee’s…flawed, neurotic, anti-hero rejected the best standards for a hero as rational being at his best and as an agent of justice.”

While Spider-Man was never quite as much of a sad sack teen as people sometimes remember—he was never sidelined from superheroing by acne or prom issues—he was frequently mocked and derided by his peers as teenage egghead Peter Parker. On more than one occasion, Spider-Man did blunder, by, say, trying to nab crooks he saw casing a jewelry store before they actually entered the store, so that they called the cops on him.

At times, he emitted such self-pitying declarations as “Am I really some sort of crack-pot, wasting my time seeking fame and glory? Am I more interested in the adventure of being Spider-Man than I am in helping people??…Why don’t I give the whole thing up?” or “A lot of good it does me to be Spider-Man….Why don’t things ever seem to turn out right for me? Why do I seem to hurt people, no matter how hard I try not to? Is this the price I must always pay for being…Spider-Man??!”

Ditko had griped about “the introduction and sanctioning of all kinds of spoilage (flaws, neurotic behavior)” into Spider-Man. He managed the tension in his mind by emphasizing that Spider-Man was still a teen, not a fully developed adult, and that the comic could show how “Parker has to learn and grow up to be a hero,” as he once wrote to a fan.

One critic looking at Ditko’s Spider-Man work through a Randian lens, Desmond White, wondered whether Parker’s altruistic sacrifice of his time and happiness fighting crime and villains—inspired by an act of selfishness that led to the death of his beloved Uncle Ben—wasn’t perhaps a slyly Objectivist experiment in showing how altruism doesn’t lead to fulfillment. Despite a late-period Ditko Spider-Man villain whose moniker was the much-used Randian term “the Looter,” it’s difficult to squeeze Spider-Man into either an Objectivist or an anti-Objectivist mold.

Ditko’s second iconic Marvel character, one even credit-hogging Lee admitted in print “twas Steve’s idea,” was also an ironic paladin for a Randian. The core idea of Objectivism is our ability, indeed duty, to flawlessly perceive and reason from strictly defined facts of purely material reality. Dr. Strange, a master of the mystic arts, could literally make whims come true through the speaking and casting of spells, and he spent most of his time fighting impossible, unreal beings in alternate—that is, nonexistent—dimensions.

Strange’s magic peregrinations and conflicts were so bizarrely groovy, his imagery so impossibly hallucinatory, that comics editor and scholar Catherine Yronwode (who later earned Ditko’s ire while writing a never-finished book about him by prying too deep into his personal life) insisted that many of the sorcerer supreme’s hippie fans (a group that included Ken Kesey of the Merry Pranksters) were sure his creator must have had his soul psychedelicized.

Ditko, though, was not a man to fake reality, even within his own brain. While his adventures in a world divorced from observable, tangible reality seem un-Objectivist, one critic, Jack Elving, thought Strange was Ditko’s most autobiographical character: “The hermetic sorcerer who lives in Greenwich Village surrounded by books of arcane stuff and rarely leaves his room physically, while through mental projection visiting other realms actually does resemble Ditko’s lot as an artist; working in a studio surrounded by reference books and living in a world of imagination. Doctor Strange is the portrayal of Ditko’s artistic life and commitment, which leaves him lonely and isolated from other people.”

Those two Marvel characters, lately appearing in blockbuster movies that have grossed more than $16 billion for companies such as Disney and Sony, are far more famous than Ditko’s work as an Objectivist pop artist. Seeming conflicts between those distinct parts of Ditko’s career, while irresistible for critics to muse about, are best explained by the strong likelihood that Ditko’s conversion to Randian thinking had not yet occurred, or at least solidified, during the 1962–1966 period when Ditko conceived, plotted, and drew those superheroes’ adventures.

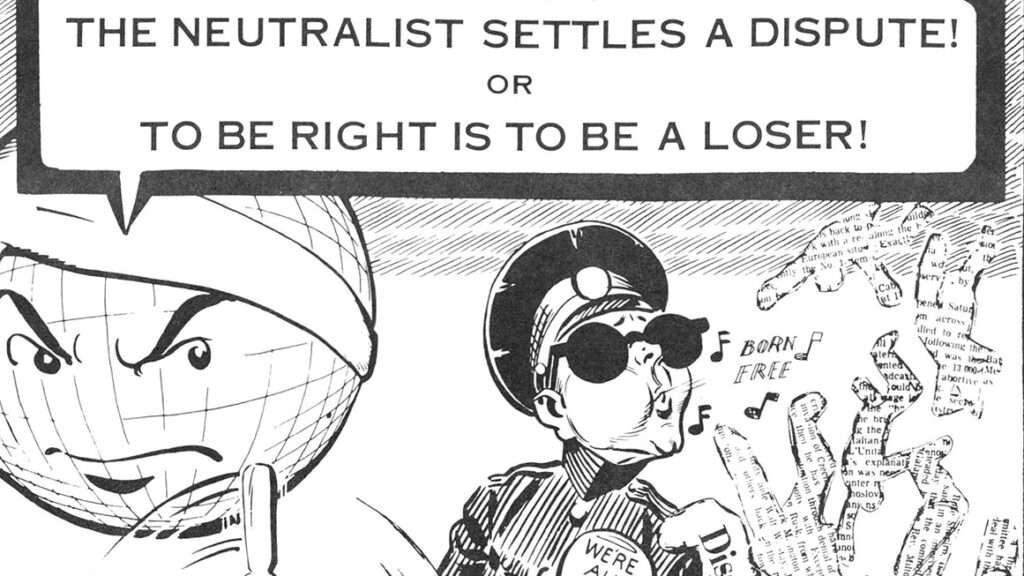

While no one seems certain when and under what circumstances Ditko became a Rand devotee—Ditko biographer Blake Bell thinks Lee may have been his entrée to her work—his unmistakably Rand-influenced art didn’t start to appear until after his first departure from Marvel. In 1967, Ditko debuted a character who would never be owned by any corporation: Mr. A. The hero was named for Rand’s core directive via Aristotle: that “A is A” and all reasoning must be rooted in never countenancing contradiction.

Mr. A is a vigilante with no superpowers—or perhaps, as Ditko wrote, his superpower is “knowing what’s right, and acting accordingly.” In a famous sequence in his first appearance, a woman stabbed by a malefactor nonetheless wants Mr. A to save the crook from falling to his death. Mr. A tells her that “to have any sympathy for a killer is an insult to their victim.”

The next year, he vividly brought Rand’s aesthetics into mass-market superhero stories in a Charlton Comic starring another of his creations, the Question, allied with an older superhero Ditko had significantly revamped, the Blue Beetle. The pair gets involved in a case centered on two sculptures, one representing man as misshapen and grotesque, the other strong and noble. They fight the artist and forces that want to promote the ugly, and thus anti-man, and thus anti-mind, and thus anti-life, art.

His most heavy-duty expression of superhero Randianism was in his independently published Mr. A stories. Ditko did have publishers for Mr. A, including first fellow cartoonist Wallace Wood and later Bruce Hershenson, who once said he “would never have made any money” from Mr. A as his adventures “were way too esoteric for the average person,” but Ditko retained ownership of the character and work.

Ditko prided himself on being a working commercial artist, willing to take on even jobs as petty or absurd as Bob’s Big Boy promos or Transformers coloring books. After all, even that was honest work, a fair exchange of value for value. But he understood that some of his more philosophical work was not for everyone, which was fine with him; it was for himself. Ditko wrote of his later work that “we are doing this primarily for ourselves and not for the purist or even for the general readers…who don’t really care about issues, content.”

Some of his politico-social essays were delivered with images he admitted were “a personal statement and not intended to entertain like a comic book such as Spider-Man.” If perplexed readers griped that this sort of work is too complex or confusing, “their complaints are accurate. We are doing this work for our own interest, benefit, understanding, enjoyment.”

Nonetheless, Ditko became convinced—not without reason, though he rarely quoted any particular evidence—that the commercial failure of nearly all his post-Marvel comics was due to fan hostility toward or incomprehension of his Objectivist-tinged ideas.

“Once I chose to become more independent (in mind/hand) in my chosen career, the negatives, the anti-Ditko, started up. I wasn’t allowed to ‘defect,’ to be a selector of my own best interests,” he wrote. Of his more Randian-coded characters, such as Mr. A and the Question, Ditko wondered: “Who did my creations…actually threaten, harm, actually DO some kind of actual abuse, harm? Who was forced to have anything to do with my published made-up characters, ideas, stories, pictures, and dialogue?” One of his one-pagers portrays a comics fan ho-humming over headlines reporting all sorts of real-world hideous crimes but going into a wild rage over a Ditko comic.

Ditko was enough of a movement Objectivist to have been a longtime funder of The Atlas Society. Jennifer Grossman, its CEO, wrote after Ditko died that the artist found the clothing in a graphic-novel adaptation of Rand’s dystopian fable Anthem to be too well-made, that the shoes the comic portrayed “could only be produced by an industrial civilization.”

Rand’s longtime friend and biographer Barbara Branden was pretty sure that Rand wasn’t personally aware of Ditko’s work. But Rand did presage his importance to the spread of her philosophy by once saying something, Branden recalled, like “when Objectivism descends from the philosophers’ ivory tower…to the popular culture, and finally reaches the comic books, we shall know that we are winning the battle.”

Random mentions of Ditko show up now and again on some Objectivist-leaning websites, but Ditko’s unique combination of pop art and Randian philosophy has been mostly as little appreciated in that world as it has been in the comics world. Chris Sciabarra, founder of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, who has written about Randian ideas in graphic literature, says, “I don’t know of many Objectivist authors or periodicals that have dealt with Ditko.”

Rand’s Roark was perhaps the most radical defender of artists’ rights in fiction, blowing up a housing project because the builders didn’t follow his original architectural plans—and convincing a jury he was right to do so with a long philosophical speech about the seminal rights of the creative mind.

Ditko had a more sophisticated set of ideas about the creator’s rights in the inherently collaborative business processes that turn an artist’s ideas into a finished physical product. Likely influenced by Rand’s general approval bordering on veneration of the businessmen who make capitalism work, he was quick to elevate and honor the role of publishers in commercial comics. For example, because Wood was experimenting with self-publishing with his magazine Witzend and gave Ditko the space to publish the first Mr. A story, Ditko wrote that it might be fair to consider Wood as co-creator of the character.

In his dogged attempts to be true to the facts of reality and property rights in the complicated business and artistic world of comics, Ditko thought a lot about what creation and co-creation meant. Creator is a near-sacred role in Rand’s world. Ditko’s relationship with Lee was forever damaged over Lee generally referring to himself as the creator of various Marvel characters he wrote, ignoring the formative roles of his artist collaborators, such as Ditko and Jack Kirby.

When Ditko finally harangued Lee into writing that he “considered” Ditko to be a co-creator of Spider-Man, Lee thought it might mend fences. It did not. Because Lee said “considered,” Ditko insisted he was still evading reality by not unambiguously stating that Ditko was the co-creator of Spider-Man.

His complicated moral reasoning about property rights in collaborative publications feeds into a curious fact about Ditko, one that makes him seem either highly principled or irrational. By all accounts, he never sold any of his original art pages.

Ditko controversially wrote in 1974 in the magazine Inside Comics that an original comic art page belonged most justly to the company that paid for it. “Who is the creator of the complete comic page? Who brings the page into being? The company is the first cause,” he said. He also thought the existing market in original comic art was a gang of thieves selling to a gang of knaves, and he wanted nothing to do with it. But his own pages that he ended up possessing were given to him by its own choice by the publisher, who he believed justly owned them. There should have been no airtight Objectivist-rooted objection to his selling them.

This was no small matter. Long before his death in 2018, Ditko’s art had become fabulously valuable, at least his 1960s Marvel pages. Ditko well might have had millions in resale value in his undistinguished office off Times Square. But there’s no public evidence he ever sold any of it. One comics writer/editor who worked with Ditko, Jack C. Harris, reported in his book Working With Ditko that at least once the artist gifted him a cover. In everything I’ve ever read by his friends and co-workers, I’ve never found a reason that made sense why he should never have sold his pages. One reported that Ditko just told him, well, he doesn’t need the money.

But his choices didn’t need to make sense to me. He was Steve Ditko, a free individual, and his choices only had to please him.

Even when Ditko was displeased with the business decisions of people or companies he worked with, he operated from a Rand-influenced understanding about the role of business and the sacredness of trades and agreements freely entered into. He quit Marvel abruptly in 1966, and various rumors circulated for decades about why. Some historians reported that Ditko felt he deserved greater remuneration as a creator than just his page rate for his creative contributions to Spider-Man, especially after the character began raking in cash via toys and TV shows. But his own essay in 2015 about why he left Marvel does not mention that concern at all. (He credits it to Lee’s refusal to speak to him anymore.) He insisted in a letter to a fan in 2015 that as far as he was concerned, “What I did with Spider-Man I was paid for.”

By the 1990s, Ditko was doing almost no work for big or even medium-sized comic book companies. He formed an alliance with the small-press publisher and Ditko fan Robin Snyder to publish nearly 1,000 pages of new comics over the last couple of decades of his life, as well as many essays expressing his ideas more directly than even his very didactic comics did.

The essays are nearly unreadably prolix, frequently using three words when one would do, like a man absolutely convinced the people he’s talking to just don’t get it. “There is a mountain of written ‘truths’ in scrolls, manuscripts, articles and published materials by the men believed and claimed to be wise, learned, most qualified,” he wrote, “who claim to have an understanding of facts, truth, life, man, right and wrong and a knowledge of everything that is true and best for man’s well-being, for human life.” That’s just one of many painful examples.

He still drew comics that seemed like they were trying to be narratives, still about good vs. evil, crooks betraying each other, a costumed hero simplified/reduced to being called “The Hero” foiling criminal plots in platonic fight scenes largely devoid of character or plot beyond “find crooks, beat them up,” but still quivering with that curious kinetic Ditko magic, his stark shapes balleting through violence meant to show the impotence of evil in the face of a generic Good.

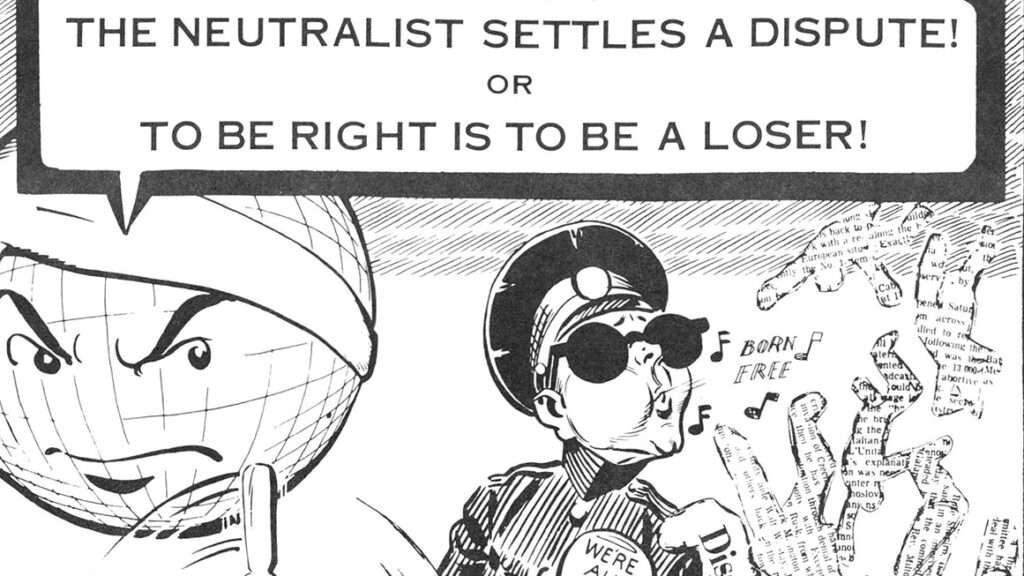

His sense of life largely lacked Randian benevolence. On rare occasions, he’d do a one-pager portraying people symbolically climbing a mountain to the land of successful achievement, but mostly he enjoyed portraying sputtering crooks double-crossing each other and whining complainers demanding the unearned. In the last decade of his life, Ditko drew more comics about comics fans not liking his comics than he drew about productive, happy people. His heroes defeat villains, yes, and win in that sense, but they are merely symbols, never human beings of the richness and complexity of Rand’s characters. He was often, in the most insulting old-fashioned sense of the term before graphic narratives achieved cultural respectability, doing a comic book version of Rand.

Still, even some comics intellectuals who weren’t devotees of Rand’s ideas appreciated some of Ditko’s more bludgeoningly Randian work as formally innovative. Ken Parille praised his famous work “The Avenging World” (which appeared in Reason in 1969) because Ditko “had the nerve to reject the cherished (and false) notion that comics is fundamentally a storytelling medium….[‘The Avenging World’] is a landmark in American comics history, an expansive work that wildly transgresses comics form: it’s a non-narrative comic with embedded narrative episodes, and it moves in and out of very different modes of representational and abstract drawing styles. In comics like this and so many others, Ditko reinvented the medium.”

Ditko’s themes and techniques haunted later important creators of comics, including Alan Moore of Watchmen fame and Frank Miller of The Dark Knight Returns, who dragged superhero genre fiction into the light of “serious adult lit cred” in the mid-’80s while relying on Ditko’s visions of vigilantism, particularly the idea that heroes had a right, perhaps even an obligation, to kill criminals. Some call that antiheroism, but Ditko’s Objectivist-inspired vision told him that people forfeited their own right to life when they refused to respect others’.

Ditko’s Objectivism, from outside admirers’ perspective, ruined him as a popular artist, leading him to didactic hermeticism and to a more and more cranky sense of what sort of interference he could tolerate from editors whose values he did not share.

But that is not how Ditko saw it. In one of his many one-pagers about his torturous relationship with comic book fans in 2008, he drew a hideous fan tearing up a comic book and crying, “That Ditko!…Can’t the *@# stop being himself…be anybody but Ditko?!?” (The aggrieved fan is labeled “the Non-A.”)

Ditko’s the Question answered it, with a credo by which any artist, Objectivist or not, could lay his sense of his work and its posterity: “When does a man achieve victory? When after he has honestly applied himself to the task facing him and having overcome it…is secure in the knowledge that whatever he has accomplished, the fruits of that goal belong to him! He will know…no one else matters.”

This article originally appeared in print under the headline “The Howard Roark of Comics.”