THE invitation from the Church Times was absurd, but irresistible: to go to the V&A East Storehouse in Hackney Wick, use the magnificent new scheme that lets you order up five objects, which will be got out for you to look at, and arrange them into a tiny museum of Christianity. The challenge turned out to be as enjoyable as it was preposterous.

Wandering through the galleries of the V&A in South Kensington is an intense pleasure, if a disconcerting one. English domestic furnishings without warning give way to Buddhist sculpture; you stray from Japanese textiles into medieval metalwork. It is easy to miss the fact that, within the sections, each object has been carefully chosen, each grouping carefully crafted, to locate that object in a narrative of changing taste or evolving skill, new technologies or social upheaval.

It is even easier to forget that this abundance of great and beautiful things is just the tip of an enormous, amorphous iceberg. The unseen bulk of that iceberg is the research collection, the more than two million objects that the museum keeps stored, so that we — all of us — can study how and why people over the centuries have made useful and beautiful things.

What is laid before us in South Kensington is the table d’hôte, the set menu, selected by the Museum’s maîtres d’hôtel (today, most are actually maîtresses) — the expert, erudite curators.

If you want to go à la carte, explore the iceberg below the water and construct your own gallery on the theme of your choice, then head for V&A East. The Museum’s new open storage facility in the former Olympic Park in east London is designed to stun the visitor into speechless delight, and it does.

In a cross between granny’s attic and Aladdin’s cave, you either stroll enchanted through stacks of haphazard “Major Tom”. Or, in an admirable new initiative, a kind of cultural Deliveroo, you can order any five objects in advance, and they will be made available for you to see close up.

Vicky WalkerNeil MacGregor examines a dish at V&A East Storehouse

Vicky WalkerNeil MacGregor examines a dish at V&A East Storehouse

The objects you can pre-order are all on line; so you can surf through the odd, beautiful, moving, disregarded, battered, thrown-away things that are essential for deep research, but would crowd out a gallery in South Kensington. I typed in my filter — “Christianity” — set off, and immediately: treasure!

A resplendent sequence of creations by Dior. Hadn’t expected that. A neglected aspect of the post-war Catholic revival in France? “New Look” vestments for a stylish Parisian cleric? Sadly, fool’s gold. My lousy typing had left a gap after “Christian”, and a fashionista algorithm had done the rest. But imagining those chic chasubles had been a happy moment.

This kind of object-surfing and speculating is exhilarating, addictive, and glorious in the randomness of where you land. Dior’s 1950s evening gowns quickly disappeared, replaced by early Christian Egypt c.400.

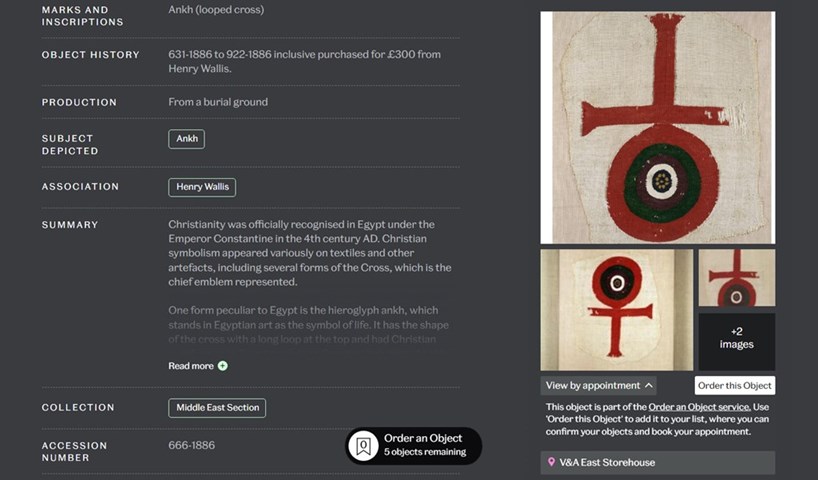

No haute couture here, but a tattered bit of white linen, with a red cross woven into it. So far, so familiar, I thought: an early step on a red-cross journey that might in due course lead me to the flag of St George, then on to nurses’ uniforms in war zones. But, the more I looked, and read the explanatory text, the more intrigued I became. Time to stop surfing and ponder. Because this — its museum number is “Textile 666.1886”, should you want to peruse it yourself — is not an ordinary cross.

Its lower “arm” is a looped circle, with concentric rings, which makes the cross into an ankh — the ancient Egyptian hieroglyph that had for millennia represented the breath of life. I was looking at not one, but two symbols from quite different traditions, that each proclaim the divine power to bestow life, both here on earth and beyond the grave.

The person who made this fragment of cloth was weaving the Christian faith into a much older, familiar pattern of belief and hope: the ankh reminds us that the religion of the Pharaohs had also held that the spirit lived on after the death of the body — which was after all the key rationale for mummification.

But if it was easy to see what the weaver of the red cross was doing, it was much harder to say why. What, I found myself wondering, did they — the maker or their patron — actually want to tell us? Were they loudly proclaiming the triumph of the all-victorious Cross over the ankh of the Gentiles, and particularly over the Egyptians who had oppressed the children of Israel?

Or is this double symbol in fact evidence of the opposite position: that many Egyptian Christians stayed true to the old beliefs and saw no need to discard the faith of their ancestors, while also adopting the state religion imposed by the Roman Emperor? Or were they gently reminding us that when it came to life, death, and judgement, this new Christian faith was not really so new after all — that when the Nicene Creed was drafted, Egyptians had already been acknowledging the divine breath or spirit as “the Lord and giver of life” for several thousand years? A textile can hold ambiguities that a mere text can only dream of.

BUT I decided that my first V&A East order would be not where the Church began, but where the Church Times started: in the mid-19th-century debates about the Church of England and the Church of Rome. So I asked for a piece of Pugin. And when I got to Hackney Wick, it was waiting for me.

Pugin designed this sumptuous square of red and gold brocaded silk in 1848, as an apparel, an alb decoration. In almost pristine condition, it catches the light as you hold it, glowing, gleaming, glinting. It is easy to imagine the impact not just of the complete vestment, but of the splendid procession that it was designed to be part of.

But these few square inches of fabric evoke much more than a procession. They carry a whole ecclesiology. This apparel was given to the Museum by St Augustine’s Abbey, Ramsgate — the church that Pugin built next to his own house, funded himself, and conceived as the ideal church for the Catholic England of which he dreamed. It was to be shaped and decorated on high medieval lines, with patterns like this, and it was dedicated, of course, to the man who had first brought England into communion with Rome. Pugin was still working on it when he died in 1852. This square brings you very near him.

FOR MY second piece, I wanted to get close to where my own engagement with the structures of the Church had started: baptism in the family christening robe. The V&A has a run of christening robes from the 18th century onwards. I asked to see the one that looked closest in appearance and date to the one in which I became an infant member of the Church of Scotland.

Image courtesy of the V&AAlabaster panel (fragment) depicting the Annunciation (English, c.1400-30, A.42— 1946)

Image courtesy of the V&AAlabaster panel (fragment) depicting the Annunciation (English, c.1400-30, A.42— 1946)

Although roughly the same size, the Museum’s robe, from around 1850, was a distinctly grander affair — embroidered, with an inset panel of muslin, and trimmed with Maltese lace. A moth hole and a small bloodstain (the result of a careless safety pin?) suggested that, in the years before it entered the Collection, it had, like most family robes, been stored long and used often.

Part of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s promotion of their virtuous domestic life was the illustration in the popular press of their family rituals: the Windsor Christmas tree, of course, but also, from the early 1840s, the christening of their children — in the royal family robe. The V&A robe shows how quickly the fashion spread, and it went far down the economic scale.

By the mid-19th century, machine production had dramatically reduced the price of lace in Britain (think those acres of twitching Victorian lace curtains) and a robe like the one that I was christened in, made of cheap cotton and manufactured lace, a distant humble copy of a royal robe, was within the reach of aspiring entrants to the middle class, like my Scottish ancestors.

It was usually, along with the family Bible, the only heirloom, passed down — in our family — from mother to eldest daughter, who made it available for the ever-wider cousinage. My grandmother and mother had been christened in the robe I wore, as were my siblings and all my cousins. Then the dwindling began. Not all my nieces and nephews, and not one of their children, have been christened.

As the Church has retreated from the life of the country, the christening robe has become an heirloom without a purpose, which can never be used, or even shown. Rather than lying camphor-wrapped in a drawer (to avoid that moth-hole), it, too, probably now belongs in a museum.

FROM 1400 onwards, across the whole of Europe, the prosperous devout, eager to sharpen their focus in worship and prayer, turned for help — to Nottingham. There, a plentiful local supply of alabaster, easy to carve by even the moderately skilful, had turned the region into an industrial-scale centre for the production of high-relief sculpted plaques, showing single saints, or scenes from the life of Christ or the Virgin.

They sold well in England, and developed into a lucrative export business. Modest in scale, brightly painted, and often lavishly gilded, they could be used singly at home as an up-market (but still affordable) version of a coloured wood-block print; or they could be combined into large narrative sequences on an altar. The pilgrim who completes the Camino to Santiago de Compostela today will find in the museum there a splendid altarpiece telling the story of St James in brightly coloured Nottingham alabaster panels — the offering of the English pilgrim John Goodyear in 1456.

Screenshot of the V&A website showing an Egyptian hieroglyph ankh, one of thousands of items available to order to view in person

Screenshot of the V&A website showing an Egyptian hieroglyph ankh, one of thousands of items available to order to view in person

Used in the home, panels like these accompanied a widespread movement of private devotion, of direct conversation with God and the saints in the home, not the church, which did much to roll the pitch (as our politicians would now say) for the Reformation. And it was the Reformation that did for Nottingham alabasters — especially the more extreme iconoclastic spasms of Edward VI, like the Putting Away of Books and Images Act of 1549.

Most of the alabasters in churches, and many in homes, were smashed. On the Continent, several great altarpieces survive in churches, but there are few now in England — and the greatest collection of plaques anywhere is today in the V&A. The most beautiful and best-preserved are, of course, on show in South Kensington, but I wanted to see a run-of-the-mill work, and chose one that had been smashed, almost certainly in a frenzy of Puritan image-destruction.

This fragment of an Annunciation shows us the Virgin (or at least her body) kneeling at prayer, with a tiny Book of Hours in front of her. To the left are the lilies that symbolise her purity, and we can assume that, before she was beheaded, she was turning to look at the angel, flying in at top left.

It cannot claim to be a great work of art. The proportions of her body between knee and waist are alarming on close inspection, but the folds of her dress do suggest a sudden, startled movement as she responds to Gabriel’s unsettling greeting. It could have been one episode in a cycle of the Life of the Virgin, or a single, private piece.

Kneeling in front of an image like this, I think, you can easily imagine yourself praying more intensely, with Mary near you as companion, guide, and intercessor — and perhaps also imagine what it would mean to be, like her, interrupted by an angel. It is even easier to understand the rage of much of the population at seeing such familiar, comforting images being forbidden by law, or smashed by the zealous, in the name of fighting idolatry.

This bruised, scratched fragment stands for huge quantities of religious art, public and private, that perished in the Protestant cataclysm, as across England and Scotland the Word violently vanquished the image. And, in the area round Nottingham, hundreds of craftsmen-carvers had to switch their workshops’ production away from making small plaques for export to providing large monumental tombs for local Tudor grandees. In the parish churches of England, alabaster now glorifies not the saints, but the rich.

A COUPLE of hundred years later, affluent Continental Catholics were in pursuit of a different kind of image to demonstrate their domestic piety — and their worldly success: biblical scenes painted on extremely expensive imported Chinese porcelain. The translucent white surface (which at that date no European ceramic could match) gave the painted colours an arresting intensity, as in the bowl you see here. Made around 1730, it is about the shape and size of a modern pasta dish, but was surely intended not for use, but for contemplation or display: an exotic devotional luxury.

Image courtesy of the V&ACrucifix clock (French, 1650. 4095 — 1857): a crucifix on a pedestal of ebony with applied silver ornaments, the figures of Christ, the Virgin, and St John are gilded metal; the clock movement in the pedestal turns a crown-shaped dial at the top of the cross; two angels on the arms of the cross point to the revolving dial

Image courtesy of the V&ACrucifix clock (French, 1650. 4095 — 1857): a crucifix on a pedestal of ebony with applied silver ornaments, the figures of Christ, the Virgin, and St John are gilded metal; the clock movement in the pedestal turns a crown-shaped dial at the top of the cross; two angels on the arms of the cross point to the revolving dial

By this date, the Dutch East India Company, the first global multi-national, was importing large quantities of plain porcelain from China, which were then decorated for the European market. Here the (probably Dutch) painter worked from a print after Rubens’s celebrated 1620 painting of the Crucifixion in Antwerp, known as the Coup de Lance (the V&A has the oil-sketch for it).

It shows the moment where the centurion pierces the dead Christ’s side with his lance: the redeeming blood and water have begun to flow, and the centurion, recognising the Son of God, will be the first person converted by the Passion. A hundred years after its making, Rubens’s image of suffering, salvation, and conversion was still famous, reproduced in engravings, and admired and copied across Europe.

The porcelain of our dish was Chinese and precious; the painting on it is European and lamentable. The artist has been unable to catch the tragic, energising pathos of the original Rubens, and we are left with clumsy contortions and empty simpering. Bad art can, of course, inspire deep piety, and we have to hope that was the case for the proud owners of this piece.

This bowl seems unlikely now to inspire devotion, and yet it remains for me an intriguing piece of economic history — evidence of faith following fashion, of how images spread into all media through the print market, and an early product of that modern topic of concern, a complex global supply chain.

ONE OF the founding purposes of the V&A was — and still is — to show what can be achieved in different materials. So, after textiles, stone, and ceramics (with a nod to paper), I wanted to finish with wood and metal.

Christ hangs high on an ebony cross, inlaid with silver and standing on a skull and crossbones. Far below, or so it seems (the whole object is just over a foot high), stand the Virgin Mary and St John, slightly smaller in scale. The figures are gilt-metal, and the modelling of the entirely gilded body of Christ is particularly fine. On the arms of the cross, two silver angels point to a crown of gold.

The silvered head-band that supports it is engraved with Roman numerals; for this sculptural group, made in France around 1650, and designed to stand on a table or a private altar, is a clock. Controlled by the mechanism concealed in the base, the silvered band rotates, so that the time appears over the head of Christ. As he looks down at the person kneeling in prayer, a small bell strikes the hours. Every hour of every day, he is being crucified.

Image courtesy of the V&AA W. Pugin textile alb decoration (an apparel) (1848, T.301F — 1989)

Image courtesy of the V&AA W. Pugin textile alb decoration (an apparel) (1848, T.301F — 1989)

In France, as in England and Holland at this date, clock-making was at the cutting edge of scientific research. The pocket watch was about to make its appearance. The mechanism of springs and wheels underpinning this sculpture, precision-made in brass, is up to date and top of the range. Art and science come together here at a high level. And so, more unusually, do technology and theology. This crucified Christ has a square halo. It is a form used to emphasise his temporal presence on earth, living among us, being with us, not once, but for ever. This victory over death — the skull at the foot of the cross — is achieved by the Lord of the Years, the Potentate of Time.

Neil MacGregor is a former director of the British Museum and the author of Living with the Gods (Allen Lane, 2018).

To use the Order an Object service at V&A East Storehouse and select up to five objects to view in person, visit: vam.ac.uk/east/storehouse/visit