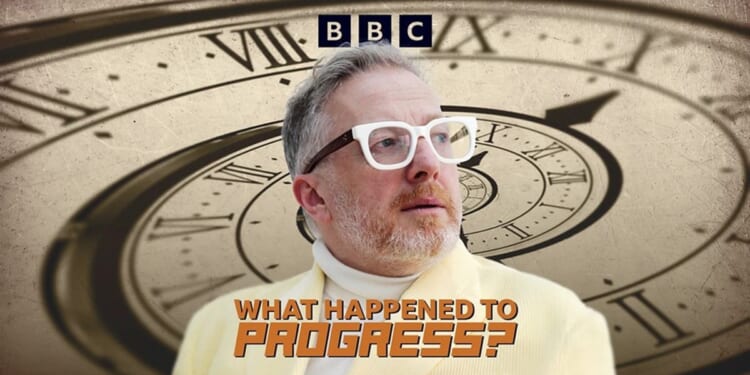

IN THE second of a four-part series, What Happened To Progress? (Radio 4, 5 January), Matthew Sweet explored a crisis in the actually dominant faith of our times.

The interviewees covered a wide spectrum of views, from the Canadian psychologist Steven Pinker, who spoke of the upward movement of many graphs in the industrial era as evidence that things really did get better, to Professor Rupert Read, of the Climate Majority Project (Comment, 9 January), who said that “most of the time” progress “makes things worse”.

The programme also ranged entertainingly widely, from cyclical understandings of time in pre-modern civilisations, via the horrors of scientific racism, to the techno-ecologism in the early West Coast internet scene.

Its central theme, however, was an evaluation of the idea that human ingenuity will inevitably secure the material required for Adam Smith’s “natural progress of things towards improvement”.

Sweet’s reference to “our expulsion from Eden” as a counter-narrative demonstrated the continued power of biblical themes, even in a culture in which progress is often defined partly in terms of abandonment of religion.

I was wary of Sweet’s wish to replace the human desire “to remain at the centre of all things” with a fresh awareness of our dependence on ecological networks. The Bible says that both those things are true: we depend on a God-given network of life, yet are indeed the most important thing on the planet, uniquely made in the image and likeness of God. Presenting humans as simply one life form among many risks, in practice, diminishing the value of humanity.

A new political economy that intertwines prosperity and ecology sounds obviously necessary. As always, the devil will be in the detail. Sweet concluded the episode by discussing the possibilities of improving human self-understanding. This attack on progress is, at root, very progressive.

Sunday (Radio 4) had a melancholy report from the last ever mass at Holy Family RC Church in Port Glasgow, one of 328 churches in Scotland which have closed since 2020.

Anglicans sometimes have a sense that they have declined more than other — especially more conservative — denominations. Statistics don’t bear this out. Holy Family’s closure is the latest episode in the crumbling, in the space of a generation, of a world of Irish and Irish-descended Roman Catholicism on both sides of the Irish Sea which recently seemed unassailable.

The 1950s building was designed by the famed Scottish High Modernist architectural practice of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia. Churches of the era are notorious for the use of experimental materials that didn’t work in practice. Holy Family’s rebar design was doomed from the start to rapid corrosion in its dreich maritime location. The High Modernist moment looked towards a future of beneficent and inevitable progress through the application of rational principles: one that never emerged.