A REPORT on conflict-related sexual violence in Sri Lanka will “increase awareness” and “generate momentum” for meeting the needs of isolated Tamil survivors, it is hoped.

Typically, survivors of such violence (CRSV) in Sri Lanka have been subjected to repeated violations, the report says. Often, they have been “forcibly recruited to fight, repeatedly displaced, bombed, shelled, starved, denied medical aid, arbitrarily detained, tortured, and have witnessed enforced disappearances or summary executions”.

The report, Opening a conversation: Justice and reparations needs of exiled Tamil survivors of conflict-related sexual violence, describes the effect of CRSV on survivors, families and communities. It is the result of a two-year participatory consultation.

This involved 11 mixed-gender group meetings with sexual-violence survivors, consisting of approximately 40 men and ten women, “reflecting the composition of the population of survivors of CRSV from Sri Lanka in the UK”.

Group members reported psychological symptoms of their detention and sexual torture as “stress, fear, frustration, suicidal ideation, ‘deadly nightmares’ and insomnia, as well as loneliness and poor self-worth”.

A “common torture practice in Sri Lanka”, the report says, is cigarette burns on the upper arms or back. These are visible when a woman wears a sari blouse and reveal to the community that she has been sexually assaulted.

Participants reported that the trauma and physical violence had led to “chronic difficulties in breathing, due to injuries or panic attacks”. They also expressed concern about contracting sexually transmitted infections, “which often go undiagnosed due to stigma and the lack of adequate healthcare in Sri Lanka”.

Discussions “allowed participants to reflect not only on individual trauma but also on collective trauma and community, and to find some healing in solidarity”, the report says.

It was published on Thursday of last week by the International Truth and Justice Project, as part of the Global Reparations Study, launched by the Global Survivors Fund (GSF) in 2020.

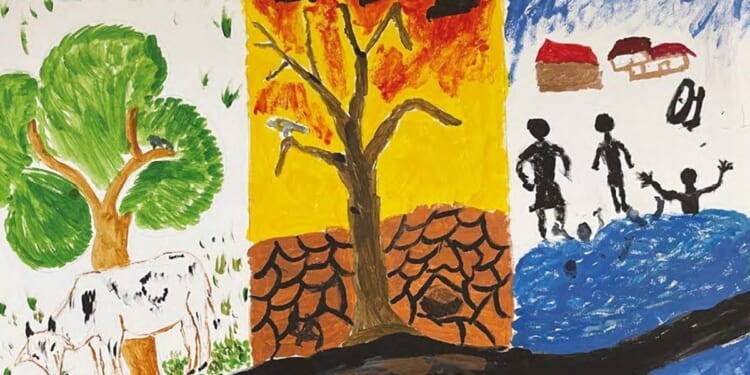

Tom NewmanTamil survivors take part in an art class

Tom NewmanTamil survivors take part in an art class

The Project, an NGO that gathers evidence to hold the Sri Lankan government accountable for war crimes, was established in 2013.

The director of the Project, Frances Harrison, an author and former BBC foreign correspondent, told the Church Times: “Our project is survivor-led. Our staff were in the final war; they’re recent refugees. They’ve been through similar experiences, and that’s one of the reasons why our project works, because people will come to the project and they understand those that run it.”

Tamil survivors of torture or sexual violence were very isolated, Ms Harrison said. “They have been held in solitary confinement, tortured alone, raped alone, smuggled out of the country alone, lived somewhere in some horrible room here alone. They are often fearful to even ring home, because they feel they’ll put their family there at risk. It’s almost like they’re in solitary confinement, even when they’re not in detention in Sri Lanka.

“Coming together in a group where they eat the same food, speak their language, and also where everybody has been through similar experiences, helps them understand that it’s not their fault what happened to them.”

The report includes an annexe that sets out the context of CRSV in Sri Lanka and cites independent confirmation from the United Nations. Ms Harrison received feedback on the first drafts of the report. “We . . . had several goes at writing it before we felt that we’d done it justice, and managed to separate out the voices of the survivors from the more legalistic, political context. . . There’s a very organised system of denial [in Sri Lanka], and we had to stand up the fact that there was CRSV in the first place before we could address the actual experiences of people who suffered that.”

One survivor is quoted in the report saying: “There is virtually no legal system to deal with victims of sexual violence. The legal system does not have a solution to our problems. And even when we try to make someone accountable, they find another 10 ways to escape the legal system, and perpetrators are not punished, and they have impunity.”

Ms Harrison emphasised the importance of collecting information and evidence “while people can still remember it, and they’re alive. If you don’t collect that information immediately, then you have no hope of criminal accountability down the line.”

The Church Times has seen the testimony of three survivors who took part in the consultation on which the report is based. One 45-year-old woman and her family were first displaced in 1993. In 2023, she was abducted and accused by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of being a member of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and of “making Sri Lanka look bad”. She said that she was forced to sign papers written in Sinhalese, a language that she does not understand, and physically and sexually assaulted while she was unconscious.

Another survivor, a 28-year-old man, said that he was “tortured and sexually tortured” by the CID. “I feel that I will get some release by sharing this story with [the ITJP] and also some justice for what happened to me,” he said.

An existing rehabilitation project, initiated in 2016, is hosted at a church in London (not named for privacy reasons). The programme includes therapeutic art and English classes, and the teachers are also involved in the group consultations. Survivors used word maps and take part in individual and collective drawing and painting during breakout groups to convey some of the concepts.

Sue Waites, who has been a parishioner for the past 50 years, told the Church Times that she first signed up as a volunteer eight years ago.

“To me, it’s so much like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, because, each week, we bind up the wounds of the afflicted, and, using their statements and documentation, we try and poke a stick in the wheel of the oppressor and keep the Sri Lankan government accountable.

“The difficulty is not sharing the language, but just being able to hold on to them when they are weeping. I’m glad to be with them.”