WORKING-CLASS candidates continue to experience a “cultural loss” of identity when exploring a vocation to the priesthood, as well as both academic and financial barriers to training, a paper due to be debated by the General Synod next month says.

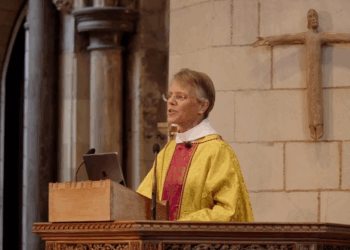

It was written by the Bishop of Barking, the Rt Revd Lynne Cullens, who chaired a “task and finish” advisory group, commissioned by the Ministry Development Board (MDB), and the Bishop of Chester, the Rt Revd Mark Tanner.

Last February, the Synod voted unanimously for the development of a national strategy for encouraging, developing, and supporting vocations of people from working-class backgrounds, both lay and ordained; and for the MDB to bring that back for debate within 12 months (News, 28 February 2025).

The private member’s motion last year was brought by the Vicar of St Matthew the Apostle, Burnley, the Revd Alex Frost, out of a concern that “some people from a working-class background with a calling to ministry have found it difficult to progress because of expectations and assumptions based on their social class.”

His speech received a standing ovation. As well as the advisory group, the MBD also commissioned a church-wide consultation process, alongside testimonial films.

The 20-page background paper (GS 2435) due to be debated at the next sessions acknowledges the “hurt, anger and frustration” expressed at consultation meetings, along with a cautious hope that “class dynamics were being talked about”. It also acknowledges “a strong reaction against the question itself being ‘othering’ and demonstrating a power imbalance”.

It summarises the main barriers to training as “the overly academic nature of training in the Church of England, or at least the perception of it”. Reflections included the experience that “having a strong regional accent could mean you are perceived as being ‘thick’.”

The report identifies the financial challenges to accessing training. Comments about “the ‘posh’ nature of TEI[s’] [theological-education institutions] having an alien and impenetrable culture were frequent”, it says. There were also positive stories of TEIs’ engaging working-class students well: “The subject of class engagement in the training sector is already bearing fruit,” the paper says.

The main area of concern over training was around housing. While the recent clergy well-being package was discussed, and the benefits were clear, “many are hesitant to give up social housing, as they are vulnerable at retirement in what they may secure from the church or elsewhere.” Some felt that the system was still geared to the home-owning section of society.

“Coupled with the lack of trust that exists in the Church around retirement and housing provision, [it] creates a situation that is not conducive for encouraging working-class vocations to ordained ministry.”

Feedback on elements of culture and leadership formed the most nuanced discussion, the paper says. “Those who do explore vocation . . . too often report a sense of ‘cultural loss’, having felt a need to lessen their working-class identity in some way to be able to ‘get on’ in the institution.

“More broadly, people’s sense of cultural loss can be felt because their working-class experience and background is dismissed as not being relevant to the skillset any minister might need.”

The perception that clergy, in particular in the C of E, were perceived as middle class was not actually true, but still “loomed large enough” in people’s thinking “to the extent that some working-class clergy ministering in working-class congregations are not seen as working class because they are a priest (‘all priests are middle class; you are a priest; therefore, you must be middle class.’”

The report concludes: “Fewer barriers, more leaders with working-class roots are the clear and simple call of this paper. . . This is an issue of social justice that everyone should be concerned about. . . Careful work must be done to increase trust and build the sense that ‘we are all in this together’ and that ‘church is not done to’ those without a voice by those that have it.”

It also describes this as “an incredibly hopeful moment”. It says that there had not been time to produce a national strategy in detail, but the advisory group had “put the work in to encourage working-class vocations at a national level and as a permanent fixture”.