Over the last several decades, rising housing costs in California have been explained as a simple supply-and-demand problem: more people, fixed land, higher prices. But a deeper look into the data tells a more precise story.

A simple comparison across the South Bay region of Los Angeles County, such as Lomita, Torrance, and Redondo Beach, shows exactly when housing costs stopped tracking incomes, why affordability deteriorated, and how state housing policy made the problem worse rather than better.

1970 → 1980 → 2025

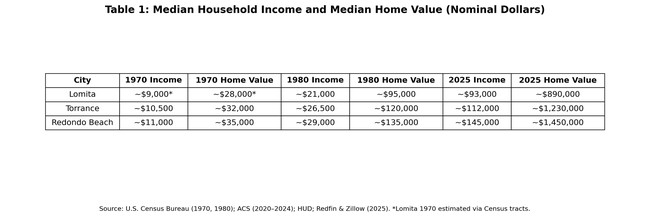

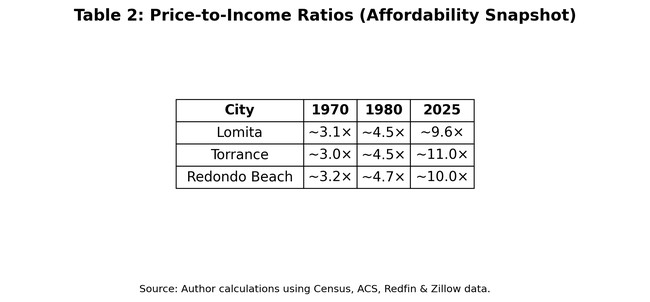

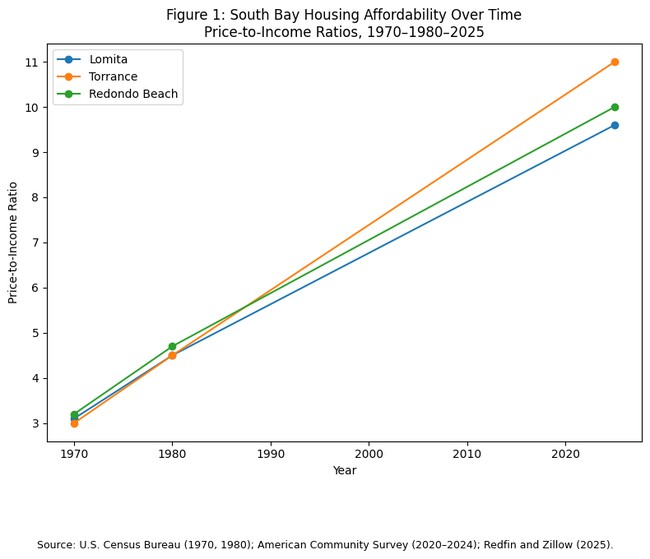

By 1970, the South Bay was approaching the point of being largely built out, like a lot of coastal cities in California. The post-World War II housing boom had done its job. Homes were modest, neighborhoods were stable, and housing costs tracked incomes. At the time, a typical home cost about three times the annual household income.

That was affordability.

By 1980, the South Bay had crossed the affordability Rubicon. Housing costs no longer tracked incomes the way they had in 1970. Price-to-income ratios moved into the 4.5× range (see Table 2). Not catastrophic, but unmistakable.

What followed was not a sudden crisis, but a slow, compounding gap.

By 2025, that gap had exploded. Homes now cost nine to eleven times the median household income across the South Bay (see Table 2). At that level, ownership is no longer a function of work. It is a function of inheritance, existing equity, or dual six-figure salaries.

Inflation Didn’t Cause This

Inflation Didn’t Cause This

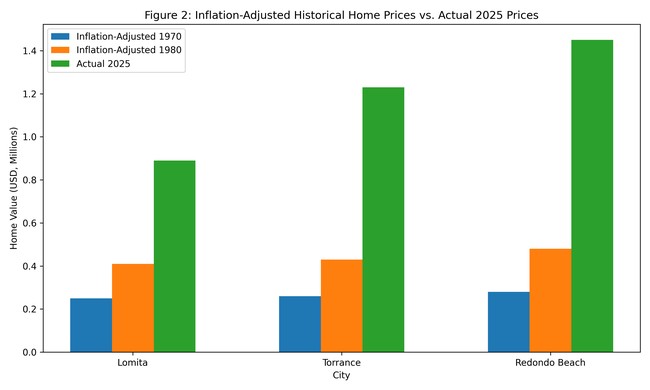

If inflation were the explanation, South Bay homes today would cost a fraction of what they do. Adjusted for inflation, a typical home from 1970 would be priced between roughly $225,000 and $280,000 today, while a 1980-era home would fall in the $340,000 to $485,000 range. Instead, actual 2025 prices range from approximately $890,000 to $1.45 million, creating a structural gap that wages will never realistically close.

That gap defines the affordability problem California now faces.

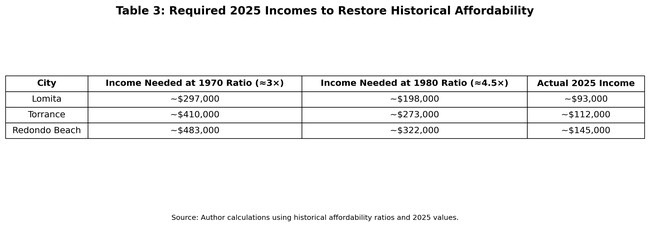

Once housing costs diverge this far from inflation, restoring affordability would require extraordinary income growth. That would mean median household incomes of roughly $300,000 in Lomita, $400,000 in Torrance, and $480,000 in Redondo Beach (see Table 3). In practical terms, median incomes would have to triple or quadruple almost overnight, an outcome that is neither realistic nor achievable.

Once housing costs diverge this far from inflation, restoring affordability would require extraordinary income growth. That would mean median household incomes of roughly $300,000 in Lomita, $400,000 in Torrance, and $480,000 in Redondo Beach (see Table 3). In practical terms, median incomes would have to triple or quadruple almost overnight, an outcome that is neither realistic nor achievable.

Which leaves only one lever that matters: supply, but only the kind that actually pencils.

In cities like Lomita, Torrance, and Redondo Beach, supply cannot be added the way it was in 1955. Most parcels already have structures. New housing requires replacement rather than expansion, and every new unit displaces something else. And that changes the economics completely.

In cities like Lomita, Torrance, and Redondo Beach, supply cannot be added the way it was in 1955. Most parcels already have structures. New housing requires replacement rather than expansion, and every new unit displaces something else. And that changes the economics completely.

SEE ALSO (VIP): LA Builders Flee: Bureaucracy and New Taxes Crush Apartment Builders

Greenfield housing is cheap. Replacement housing is expensive. That is the core constraint modern housing policy refuses to acknowledge. California instead chose policies that made housing approvals slow, risky, and costly.

And once a city is built out, there are only four ways to add housing.

Teardowns and replacement dominate California today. A $1.2 million home is torn down and replaced with a $3 million home. Net new units: zero. Net affordability: worse. This technically counts as development, but it does nothing for affordability.

Vertical growth in limited nodes can work, but only in specific locations with infrastructure upgrades tied to growth. Done everywhere, it breaks trust. Done nowhere, it strangles supply. Local planning beats blanket mandates.

Redevelopment and reuse of strip malls, underused offices, industrial parcels, and surface parking lots is real supply, but finite and capital-intensive. It produces affordability only if projects are allowed by right and costs are controlled. State mandates help less than advertised. Cost structure is the real constraint.

Incremental density is the only scalable option. Duplexes, fourplexes, ADUs, small apartments, and mixed-use along aging commercial corridors can add supply, but only if approvals are fast and predictable. When approvals take years, small builders disappear, and luxury housing is all that survives. Again, local control matters here.

Cities know which corridors can absorb modest density without destroying neighborhoods.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Supply and Job Growth

“Just build more housing” is a common refrain. But in built-out cities, housing can only be added through replacement and incremental density. If you do not control costs and approvals, the only housing that gets built is luxury. That increases prices.

You cannot build your way back to 1970s affordability in a built-out city. What you can do is stop making scarcity worse, allow modest growth without luxury-only outcomes, and keep working families from being priced out entirely. That requires cost discipline and local decision-making, not Sacramento checklists.

State housing policy assumes all cities have expandable land, all density is equal, and more units automatically mean lower prices. None of that is true in built-out cities. Mandates without cost control produce bigger projects, higher rents, fewer local builders, and more financialization.

That is why supply is rising in theory while affordability keeps collapsing in practice.

Others argue that the solution is attracting higher-paying companies. That approach fails for straightforward reasons. To restore historical affordability, median incomes would need to rise to top-decile professional levels. High-paying companies do not raise incomes evenly across the workforce. They raise earnings at the top, and housing prices respond accordingly.

When job growth is not matched by ownership supply, affordability worsens. Demand for housing rises immediately, prices increase, and displacement accelerates. Built-out cities face the same land-use constraints on jobs as they do on housing.

Even if a city succeeds in attracting higher-paying employers, the median household loses before it benefits, because housing demand increases faster than wages can adjust.

What Affordability Actually Means in Built-Out Cities

Here is the truth.

In fully built-out cities, the problem is not that people do not earn enough. It is that housing costs are structurally detached from incomes. You cannot job-growth your way out of that without making affordability worse.

For new entrants, affordability can only mean more affordable rental options, ownership through existing housing stock rather than new construction, and regional mobility rather than city-specific guarantees.

That is why you do not fix housing affordability by making everyone richer. You fix it by allowing people to buy earlier in regions that can still grow. That is how post-war California actually worked.

In cities like Lomita, Torrance, and Redondo Beach, new entry-level ownership is not realistic at scale. Existing homes and regional growth are the path to ownership. Supply policy must focus on cost discipline, not just unit counts.

That conclusion is uncomfortable. But it is the only one supported by the data.

Editor’s Note: President Trump is leading America into the “Golden Age” as Democrats try desperately to stop it.

Help us continue to report on President Trump’s successes. Join RedState VIP and use promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your membership.