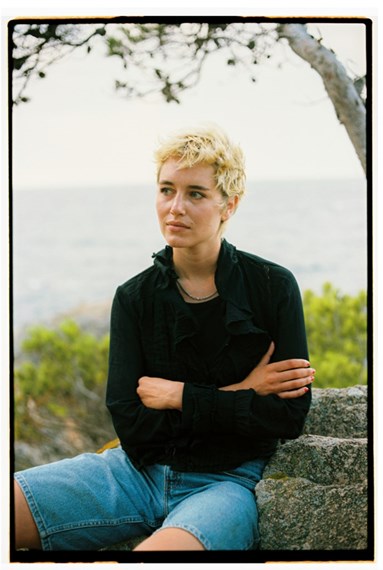

FOR Lamorna Ash, whose first book, Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish fishing town (Bloomsbury, 2020; Books, 17 July 2020) secured her the Somerset Maugham Award when she was just 25, the personal consequences of conducting research for her second book — a tour of contemporary Christianity in Britain — was never destined to provide a dramatic, surprise, denouement.

“If I kept putting myself in the way of Christianity, would I eventually be converted?” she wonders in her introduction. “I framed this as a joke aspect of my research at first, ‘Could I become a Christian in a year?’ But I’m not sure how much I was ever really joking.”

While acknowledging the “unseriousness” of her starting point (“At twenty-six, I knew that miracles and religious experiences were not real. That prayers did not do a thing. That the end of life was synonymous with finality, and to imagine otherwise was a hopeful and misplaced delusion, that churches were as useless and beautiful as dinosaur bones”), she quickly discovered that to get up close to belief, in all its strangeness, was to risk one’s “unquestioned assumptions” disintegrating.

Observing the faith of two university friends who had not only converted but were training for the priesthood in the Church of England, it was “as if the very corner of the sky had been pulled back. I couldn’t see what was going on behind it, but I understood it was there for them and that they perceived it as something vast and beating.”

Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever takes the form of a sort of journal — write-ups of the encounters that Ash had during a “perpetual Christian road-trip” that took her from All Souls’, Langham Place, to Iona, via Charismatic worship at YWAM’s headquarters and Quaker meetings in Muswell Hill (Books, 2 May). It is also an account of her “personal match with Christianity”. Her book begins with a reworking of the Genesis account of Jacob wrestling with the angel, and this theme underpins the book, written with great candour and self-awareness.

AFTER an English degree at Oxford, Ash studied anthropology at University College London. “You are taught so much about your own subjectivity, of what you are doing within a space when you turn up somewhere,” she says, in a video call. “From the very start, I understood that the more I believed in other people’s belief, the more it might have the opportunity to start changing me as well. . .

“Certainly, there were times when I felt more resistant to the forms of Christianity I was seeing. And, in other places, I suppose, the writer in me just melted away, and there I was praying on the island of Iona and weeping, and that is an entirely real feeling.” It would have felt “very strange to get rid of myself from the writing”, she says.

At one point in the book, she is challenged by an atheist Quaker about whether she is “commodifying” meetings, in intending to write about them. But, she wonders, “what would it mean to go into any religious space with a pure intention? . . . Yes, you could call it commodifying, but I guess you could also call it sharing or helping someone else to explore that. . . My sense was that those spaces were changing me as much as I was taking things to write about them, and for that I am really grateful.”

While her accounts do not eschew criticism, they also evince a readiness to question her own judgement. Early on, she writes of watching “many a male, middle-aged conservative Evangelical pastor offer their captive audiences doses of crude certainty, expressed with the urgency of the marketplace”. But, she says, “I learnt some amazing things about the Bible at ‘Christianity Explored’, when I was not too deaf, or angry, or deaf through anger to listen for them.”

PERHAPS an unexpected aspect of Ash’s biography is her request to get confirmed, made at the age of 14 to her surprised, non-religious parents. Her account of growing up at a C of E primary school is a far-from-encouraging testimony. In the only assembly that she remembers, the head teacher held up a block of wood to explain that it was idolatrous to say “touch wood”.

“As a child, I had understood — better than I would appreciate later — that there existed figures and regions beyond our visible appreciation,” she writes. “The head teacher’s lecture felt like a performance of demystification, the erection of boundary lines and partitions which seemed to make this unseen universe beyond us both more narrow and duller.”

Despite this, she tells her friends that her confirmation is born from wondering “if I might one day need God”. She recalls today an “underlying seriousness. . . I saw that life might become more difficult, and that there was something much larger that I couldn’t grapple with yet, that maybe I would need hand-holding with.”

Her work with “brilliant and sparky” teenagers in London, which entails creative writing, has underlined for her that “they are growing up in an even more plural world than we are. . . I was doing a poetry workshop, and they were all writing about their different faiths, because it was something that mattered to [them]. So maybe kids are more accustomed to belief in a God, meditation, prayer, all the accoutrements that come with different faiths.”

But she wonders, too, whether faith is “something that you mature into”. If you had asked her as a teenager about love, she reflects, “I would have these grand notions, but no lived experience.” Throughout the book, we learn the truth of the observation made by a female Anglican priest, that “God finds you when you’re low.”

In its pages, Ash identifies “a marked attitudinal shift in how my peers talk about religion compared to the generations which came before us”. This is, she suggests, an “unsteady, discordant, overstimulated, porous-bordered generation” grappling with climate change, social media, and the legacy of the pandemic. “We would like something to hold on to . . . even if that hold looks more like wrestling.”

Growing up, she tells me, she knew “the scantest detail about faith, about Christianity”, and had no idea that the Bible was “beautiful”. In her book, she records that her response to being told that “If your church is a forest, go walk in the forest,” was to wonder: “But if you have never been inside a church, how will you discover the same feeling might be accessed through a forest?

“We are so lucky to have these extraordinary spaces that were built with a kind of divinity in mind,” she tells me. “And, whether you are religious or not, that there’s something such spaces can do.” Reading holy texts leaves her marvelling at “what it means that things have persisted in time for thousands of years. There is this strange instantaneous beauty in them. There is something about being able to enter these spaces and feel the structure of that, and then getting to take that away with you elsewhere.”

While reluctant to give the Church any advice about what it should do, and cognisant that some may be nervous about crossing the threshold (“I’ve gone to churches where the first thing they do is tell you that gay people shouldn’t be having sex”), she is full of enthusiasm for simply enabling exploration.

Of young people, she suggests: “Let them enter into those religious spaces, let them read holy texts more, and again they have this armature or toolbox if they then one day want to enter into it. Knowing that every Sunday, all across the country, all across the world, these services are going on, that you can enter into quietly at the back, feels like a comfort to me.”

FOR those accustomed to the steady background hum of anxiety about the future of the Church, Ash’s book is itself a comfort: an opportunity to see the Church through the eyes of someone newly awakened to its potential. Noting that many of her friends have sought refuge in churches during times of despair, “engaged in something that approximated prayer”, she observes that there are “no other public spaces which fulfil this requirement, acting as portals to direct you to places outside of your ordinary modes of thought.”

Desirous of something “hard and bright. Not at the borders of Christianity, but right at its centre”, she finds herself “surprised by a longing for rituals”. It is at St Luke’s, Holloway, where she goes to receive communion during her travels, that Ash has, for now, found a home. “There is something about saying prayers alongside someone, singing alongside people with your terrible voice while the choir sings beautifully, that feels to me so valuable, and to my life is quite necessary.”

Her book could be regarded as timely, as the “culture despisers” of religion seem, on some evidence, to be in retreat. When it comes to statistics that some have interpreted as a revival, she suggests that “what they give is raw data without any human beings beneath it. My sense from writing . . . is that within every single congregation there is so much movable strangeness in terms of the actual beliefs that people are sitting there with, totally different contexts and backgrounds, who are taking the Bible, taking the services really differently. . .

“My feeling is that reading the Gospels can do something really quite extraordinary and transformative to you. There’s so much teaching in there that feels like radical and necessary about how we love each other and treat each well.”

In a recent feature in The Daily Telegraph (“The extraordinary resurgence of the Catholic faith in Britain”), Fr Jim Conway, who organises a mass for young adults at the Immaculate Conception, Farm Street, in London, observed that it remained challenging to get this cohort engaged in practical expressions of faith which serve others. “These young people are so strong in their faith, but the personal friendship with Jesus is a bit narrow,” he said. “As one of them said to me, they don’t have the bandwidth for more. That is our next challenge.”

Ash tells me that it’s the evident practical working out of faith which keeps her going to St Luke’s: “I think, for me, the morality and the ethics at the root of Christianity is the whole reason to go to church.”

“Christianity is still a live wire, a lightning strike through the world,” she concludes in her book. “We do not know how it will split next, what new expressions of faith might blaze through the skies, but I believe we have some say in how the lightning goes.”

Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever: A new generation’s search for religion by Lamorna Ash is published by Bloomsbury at £22 (Church Times Bookshop £19.80); 978-1-5266-6314-6.