ONE night, when she was lying in bed with her husband, Margery Kempe heard a melody so sweet and pleasurable that she thought she must have been transported to paradise. She jumped up straight away, and declared: “Alas that ever I sinned, it is full merry in heaven.”

This melody was so delectable that it surpassed any other music that Margery had ever heard, beyond comparison. Forever afterwards, whenever she heard any sound or tune that reminded her of it, she would shed plenteous and abundant tears of devotion, with great sobbing and sighing, as she yearned for the bliss of heaven.

The heavenly melody that she describes (in my translation) is one of the first religious experiences recorded in her book, the first autobiography written in English. In recounting it, Margery reveals how ardently she longed for heaven, and how much this longing shaped the rest of her religious life.

She was not the only medieval woman to feel this way. Most devotional works from the later Middle Ages are punctuated by deep yearning for union with God in heaven. One of the earliest, and most passionate examples of this is a series of 13th-century prayers. Known as “The Wooing Group”, because they describe a “wooing” between God and the soul, the prayers are anonymous, but they were probably written by a woman, for a female audience.

The poet adopts a female persona, and addresses God directly: “Why do I not feel you in my heart as sweet as you are?” the poet laments. “Why are you so estranged from me? Why can I not woo you?” Much like Margery, she imagines heaven to be a union with the object of their desire, and an end to her suffering on earth.

During my time researching the lives of European women writers, I have been struck by how often they are just as preoccupied with heaven as they are with hell. Margery Kempe, Marie de France, Christine de Pizan, and Julian of Norwich all imagine the afterlife in different ways, visualising spaces that are inflected by their own anxieties and desires.

All four, however, offer a vision of heaven which is, ultimately, comforting and hopeful. Bearing in mind that they were all writing during the Middle Ages, a time when sermons and art were often all fire and brimstone, their choice to lean into hope rather than fear can feel radical.

MEDIEVAL people were well acquainted with suffering and with death. This was a time when the Black Death twice ravaged Europe, decimating its population; when warfare raged and it was usual, especially among the nobility, to carry arms; when it was much harder to cure sickness, and mortality rates were high. For people in the Middle Ages, death could often feel frighteningly close, and there was a very real terror of hell.

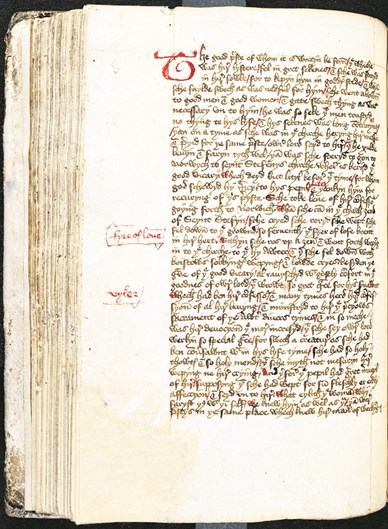

AlamyThe Book of Margery Kempe is the earliest known autobiography written in English, created c.1440. The only surviving copy of the manuscript is held by the British Library

AlamyThe Book of Margery Kempe is the earliest known autobiography written in English, created c.1440. The only surviving copy of the manuscript is held by the British Library

The walls of churches and the pages of manuscripts were saturated with the underworld’s ghastly inhabitants: monsters with mouths stretched wide, teeth glistening with blood, ready to swallow up the damned whole; devils trussing up their victims by the ankles, roasting them on spits, mutilating them and chewing them up, all the while cackling in glee. It is not surprising, then, that many medieval writers advise readers to get their souls in order before they die.

According to Christian belief, even those who escaped hellfire might still have some suffering to do before they could take their seat in heaven. Purgatory was a transitional space, reserved for those souls who had not sinned badly enough to suffer eternity in hell, but who were not pure enough yet for heaven.

The idea of purgatory had its roots in Judaism, but it slowly gained more traction in Christianity; in 1274, it was officially adopted into the doctrine of the Christian Church. In the medieval understanding of purgatory, there were no guarantees. Families could accelerate the ascension of a loved one to heaven by praying for them, but, if the Day of Judgement came and a soul still had sins left to cleanse, then they would be banished straight to hell.

The early medieval French writer Marie de France is best known for her Lais: narratives of courtly love, adultery, and supernatural adventures, which were designed to delight the nobility. One of her lesser-known works, however, is a translation of one of the most popular legends of the Middle Ages, L’Espurgatoire de Seint Patriz (”The Purgatory of Saint Patrick”), and turns its attention to more religious matters.

The story follows the adventures of a young, brave, handsome, and pious knight, Owain. When Owain asks a bishop what penance he should do to cleanse himself of sin, he is unsatisfied with the answer — the penance that the bishop describes is, to Owain’s mind, not nearly severe enough. And so, he decides to seek out purgatory, so that he can more properly prepare his soul for the afterlife.

When Owain reaches purgatory, he witnesses “every possible form of pain” — pain that Marie seems to relish describing in grisly detail. The bodies of sinners are subjected to all kinds of torment, hung up by their ankles, attacked with pokers, burned with fire, and impaled on spits until they are “blackened and charred.”

In some ways, this narrative is markedly different from Marie’s courtly love tales, which she wrote to entertain the court. For a start, L’Espurgatoire is more overtly religious. Marie was a Christian woman, and almost all her stories make mention of God, but the characters in her Lais tend to be more concerned with earthly love affairs than journeying to the underworld for penance.

On a closer reading, we can discern one significant theme cropping up time and again. Just like Owain, most of the characters in Marie’s Lais experience acute suffering. A maiden whose lover has been killed swoons four times, and then dies herself when she realises that she has lost him for good. Another maiden, who has lost her beloved, lies down next to his corpse, kisses his eyes and lips, and then dies of a broken heart. A knight agonises over the loss of his lover as he awaits execution.

Throughout Marie’s stories, love is described as suffering — a wound, a great pain, a cause of death. But, while love can so often equate to suffering in her writings, Marie also celebrates it as the most beautiful feeling in the world, something that is worth suffering, even dying for.

When Owain finally reaches heaven, unscathed thanks to his virtue, he witnesses a celestial realm filled with celebration, love, and all those souls who have made it out of the purgatorial fires: “Each of them in that place rejoiced / at their great happiness vouchsafed; / from suffering and purgatory / they had been freed.”

The heaven that Marie describes here is firmly situated in the context of an end to suffering. She is insistent that purgatory “must happen” — even those “who await true glory” in heaven must first “come to torment, suffer it” — but heaven will be all the more joyful because of it. Just as all the characters in Marie’s Lais must suffer heartache if they want to experience true love, so human souls must suffer purgatory if they want to experience heaven.

WHILE we don’t know how the anchoress and mystic Julian of Norwich died, we do know that she was familiar with the concept of “dying well” — a concept that, like purgatory, had been gaining traction throughout the Middle Ages. For many years, priests had been encouraging parishioners to prepare their souls for death. In the 15th century, a Christian committee, known as the “Council of Constance”, decreed that such advice should be consolidated into a guidebook for priests, Ars Moriendi (“The Art of Dying Well”).

Although the Ars does warn its readers about the horrors of hell which await wayward souls — horrors that are persistently and creatively grotesque — the real take-home message of the book is one of comfort and consolation. There is a good side to death, the Ars tells us, because, ultimately, death allows our soul to be reunited with its maker. It lists the various temptations that one should avoid in life, to secure a place in heaven (lack of faith, despair, impatience, spiritual pride, and avarice), besides offering advice to family members and friends.

In her Revelations of Divine Love, a series of visions sent to her from God, Julian describes a near-death experience when she was 30 years old. Incredibly ill, and believing that death was near, she sent for a priest and for her mother. She asked the priest to place a crucifix in her eyeline, and to perform the last rites, both of which are recommended by the Ars Moriendi as part of a good death. For Julian, this experience was not the end. But it sparked the visions that would make her famous and led to her decision to become an anchoress.

The term “anchoress” describes a woman who has decided to live an enclosed life, for God. Her home was a small “cell” attached to a church, with only a few small windows connecting her to the outside world, and her life became a cycle of prayer, fasting, reading, and meditation.

It also became saturated with death. Anchoresses declared themselves dead to the earthly world they inhabited, and set their eyes firmly on the next; some even went through a quasi-funeral before being bricked up — figuratively or even literally — in their cells. A guidebook for anchoresses, known as the Ancrene Wisse, recommends that its readers dig their own grave, little by little, day by day, with their own hands, to help them reflect on their own mortality; these women would never leave their cells alive.

Given the macabre nature of her profession, Julian’s theology is surprisingly and refreshingly comforting. While her contemporaries labour over the horrors of hell that await unrepentant souls, Julian is guided by God to set her sights firmly on heaven instead.

When she asks Jesus to show her a vision of hell, he refuses. Instead, he shows her many different visions of heaven. In one, God presides over a splendid feast in his heavenly house. Rather than take a seat, he busies himself by serving his guests, making sure that their needs are attended to, his face a “marvellous melody of endless love”.

In another, Julian watches as slowly, gently, Jesus stretches wide the wound in his side to reveal “a beautiful and delightful place large enough for all mankind that will be saved to rest there in peace and in love”, transforming his suffering on earth into a promise of union, rest and hope.

Most movingly of all, bearing in mind that Julian chose a life of solitude to become closer to God, is the vision in which Julian refuses to lift her eyes to God in heaven. Rather, she keeps them locked on Jesus. “No other heaven pleased me than Jesus,” she tells us. “I would rather have remained in that pain until Judgement Day than come to heaven in any other way than by him.”

By writing about what she has seen, Julian hopes to comfort and console her readers into living a good life and experiencing heaven in the next rather than frighten them into it. We should be “mindful that this life is short”, she instructs her readers, and should strive to “love God better”. Writing from a city still recovering from a horrifying and decimating plague, Julian, presenting her vision of heaven, offers hope and reminds us of how seriously she took her life’s work — to communicate God’s love to all Christians.

CHRISTINE DE PIZAN was a French noblewoman who had always shown an aptitude for study, but had set her academic ambitions to one side when she married. Her marriage was arranged by her beloved father, and it was an extremely happy one — until the terrible day when her husband, Étienne, was killed overseas, most probably by the plague.

Christine was left devastated by this loss, but, however heartsick she was, she still had children to care for and bills to pay. Rather than marry again, she decided to turn her hand to writing, becoming the first woman in European history to make a living from the vocation. It is not surprising, then, that Christine conceives of heaven as a place of learning and of knowledge.

AlamyThree women, their hands clasped in prayer,in a detail from a fresco painted c.1180 in the Crypt of the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, Aquileia, in Italy

AlamyThree women, their hands clasped in prayer,in a detail from a fresco painted c.1180 in the Crypt of the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, Aquileia, in Italy

One of Christine’s lesser-known poems, in which she herself appears as a character, is The Path of Long Study. It begins, as many of her poems do, with grief. Although it has been almost 13 years since Étienne died, Christine tells us, still her “mourning grief” renews each day. And now, it has been exacerbated by new worries about the warfare tearing her beloved country apart.

The years that Christine was writing were punctuated by significant unrest in France, as the nobility fought each other as well as England; in her later years, as the situation grew worse, Christine often tried to use her writing to bring about resolution.

It is into this context that The Path of Long Study throws us. Plagued by anxiety and seeking solace in her books, Christine goes to her study alone to read. She contemplates how the earthly world is “only wind”, fleeting, full of misery and conflict; how, under heaven, everything wages war. Eventually, she tires herself out and falls into a deep sleep, and has a vision — not an illusion, she tells us, but, rather, “a certain demonstration Of a sure and most true thing”.

An ancient sibyl appears before her, directly addressing Christine’s frustrations with the earthly world by offering to lead her “into another, more perfect” one, where Christine “can much better learn . . . the things that are truly important”.

Always eager to learn and discover, Christine follows the sibyl along the path of learning, which winds all around the world and culminates at the top of a mountain. A ladder drops down, and Christine clambers up — into heaven.

So enchanted is Christine by what she sees in heaven that she wishes all her bodily parts could be transformed into eyes, to help her to take everything in. She has never seen such beauty, she tells us, and she is only able to withstand the brightness of it thanks to the protective presence of her guide, the sibyl. She learns that there are five different heavens — although she is allowed access only to the lower ones, as the highest tiers are reserved for after death — and she is astonished by the nobility and perfection that she witnesses there.

Just like Margery, Christine describes the heavenly music and sweet smells that she encounters, but she also describes the great learning and understanding that all the inhabitants of heaven possess. The secrets of astrology, the profession of her late father, are revealed to her, and Christine describes in great detail her understanding of how the planets move and influence one another.

Although she is disgruntled not to be able to ascend to the “crystalline heaven”, where God sits surrounded by angels, seraphim, and cherubim, she is reassured to know that heaven is the antidote to everything that sorrows her on her earth. In paradise, there are no misdeeds or slander: only peace, joy, love, and concord, and, best of all, no fear of losing it.

Christine’s experience of a more perfect world makes the sorrows of her own more acute, but it also fills her with hope. When she wakes up in her study again, she is confident that she can take some of these lessons with her, to create something closer to heaven on earth. Christine’s heaven reveals not only her long-time love of learning, but also her deep desire to have an impact on the world around her to make things better for the people of France.

OWING to her piety and suffering on earth, God promises Margery Kempe that she can bypass the torments of purgatory — described in such grisly detail by writers such as Marie de France — and ascend straight to heaven once she dies. She waxes lyrical about how jubilant her passage to the next life will eventually be, imagining how she will be escorted by a whole host of holy figures, from the Virgin Mother and the twelve apostles to Jesus himself.

She envisages that, when she finally arrives, she will be “fulfilled with every kind of love” that she desires. All the saints will rejoice that she is finally coming home. All the suffering that she endures on earth, God tells us, will just increase her reward and happiness in heaven.

Loss and death played a significant part in the lives of many medieval people, and suffering to some degree was inevitable. But the writings of Marie, Julian, Christine, and Margery remind us that suffering can also be transformed into something far more enduring: hope.

Whether heaven marks an end to grief or loneliness, heralds an entry into new knowledge, or promises companionship or rest, it is marked by the lives that we live. These writings remind us that, whatever time we find ourselves living in, we all want to believe that a better place is coming, and that, when we get there, our pain will be eased.

Dr Hetta Howes is a lecturer in medieval literature at City University of London and a BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinker. She is the author of Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The extraordinary lives of medieval women, published by Bloomsbury Continuum at £22 (Church Times Bookshop £17.60); 978-1-3994-0873-8 (Books, 3 January).