The title of Walter Blair’s out-of-print classic is unfortunately obsolete, but I believe it remains a useful work. Originally published in 1937 as Native American Humor (1800-1900), it was updated and republished in 1960 simply as Native American Humor.

The book was still in print when I studied it as a high school student in 1968, the year of Blair’s retirement from the faculty of the University of Chicago, where he had taught students including Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, and four other Pulitzer Prize winners. They must have learned a thing or two about American humor from Professor Blair, although Blair erroneously advised Bellow not to pursue a career in literature. He died in 1992 at the age of 92.

Blair introduced his compilation of American humorists with a long essay that presented his taxonomy. He essentially divided the forms of American humor preceding Mark Twain into Down East Humor and The Humor of the Old Southwest. To these he added Literary Comedians and Local Colorists.

These all culminated in the work of Mark Twain, who drew the strands of American humor together. Somewhere along the way Blair made the point that Mark Twain remains funny, which is rarely the case with his predecessors. They remain mostly of historical interest. One exception that I vividly remember is T.B. Thorp’s “The Big Bear of Arkansas” in Blair’s selections of Humor of the Old Southwest.

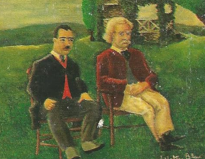

Blair illustrated the 1960 edition of the book with his own doodles. The cover portrait depicts Blair and MT lounging together. Blair explained: “I was unable to resist an invitation to have reproduced some of my works of art. On the cover is a picture of my imaginary visit (dressed in a suit borrowed from W.D. Howells) with Mark Twain in Elmira. At intervals in the text are drawings the creation of which helped me through several faculty meetings. If these do not exactly delight with their beauty, my hope is that they somehow will interpret and edify.”

Blair’s book begins with a 200-page essay on American humorists preceding his anthology of their work. His section on Mark Twain ends the book. Among his selections from MT is “The Facts Concerning the Recent Resignation,” datelined WASHINGTON, December 1867. It begins as follows and continues in this vein, still funny after all these years:

* * * * *

I have resigned. The government appears to go on much the same, but there is a spoke out of its wheel, nevertheless. I was clerk of the Senate Committee on Conchology, and I have thrown up the position. I could see the plainest disposition on the part of the other members of the government to debar me from having any voice in the counsels of the nation, and so I could no longer hold office and retain my self-respect. If I were to detail all the outrages that were heaped upon me during the six days that I was connected with the government in an official capacity, the narrative would fill a volume. They appointed me clerk of that Committee on Conchology and then allowed me no amanuensis to play billiards with. I would have borne that, lonesome as it was, if I had met with that courtesy from the other members of the Cabinet which was my due. But I did not. Whenever I observed that the head of a department was pursuing a wrong course, I laid down everything and went and tried to set him right, as it was my duty to do; and I never was thanked for it in a single instance. I went, with the best intentions in the world, to the Secretary of the Navy, and said:

“Sir, I cannot see that Admiral Farragut is doing anything but skirmishing around there in Europe, having a sort of picnic. Now, that may be all very well, but it does not exhibit itself to me in that light. If there is no fighting for him to do, let him come home. There is no use in a man having a whole fleet for a pleasure excursion. It is too expensive. Mind, I do not object to pleasure excursions for the naval officers–pleasure excursions that are in reason–pleasure excursions that are economical. Now, they might go down the Mississippi on a raft–”

You ought to have heard him storm! One would have supposed I had committed a crime of some kind. But I didn’t mind. I said it was cheap, and full of republican simplicity, and perfectly safe. I said that, for a tranquil pleasure excursion, there was nothing equal to a raft.

Then the Secretary of the Navy asked me who I was; and when I told him I was connected with the government, he wanted to know in what capacity. I said that, without remarking upon the singularity of such a question, coming, as it did, from a member of that same government, I would inform him that I was clerk of the Senate Committee on Conchology. Then there was a fine storm! He finished by ordering me to leave the premises, and give my attention strictly to my own business in future. My first impulse was to get him removed. However, that would harm others besides himself, and do me no real good, and so I let him stay….

Whole thing here.