JANE DRUMMOND, a member of the needlework team at Lincoln Cathedral, could stitch before she could read. Taught by her grandmother, she reminisced that when she had a visit, “The poor woman hardly got through the door before I’d start chirping, ‘When are we going to start sewing?’”

So, when the opportunity arose to “contribute to history”, as part of a commemorative project organised by a City of London livery company, the Worshipful Company of Upholders, she was “thrilled” to get involved.

More than 85 volunteers — like Mrs Drummond — from Lichfield, Durham, St Paul’s, Southwell, Derby, Liverpool, Lincoln, Norwich, Winchester, St Albans, Exeter, and Salisbury Cathedrals are collaborating on a 2.3-metre work of Opus Anglicanum embroidery, The Circle of Life.

The piece celebrates the 400th anniversary of the Upholders’ receiving their Royal Charter, and is to be completed by July 2026. It is an ambitious undertaking that the originator and leader of the project, Julian Squire, describes as “the only significant piece of Opus Anglicanum work that has been done in or anywhere for over 500 years”.

Opus Anglicanum (“English work”) is regarded as “the pinnacle of English embroidery”, known for its intricate use of gold and silver wirework. Mr Squire, a former Master of the Upholders, described the technique as “very, very time-consuming, detailed, and difficult to master”.

The Circle of Life piece will consist of 12 detachable outer panels depicting scenes from the livery company’s history, which can be mounted on to a funeral pall, as parts of the design will be sewn on to velcro. The inner panels will feature a silhouette of each participating cathedral, “which is like their signature”, Mr Squire says.

Volunteers at Lincoln Cathedral

Volunteers at Lincoln Cathedral

The embroidery will also include the Upholders’ crest, two sparvers (a form of canopy), and two crosses to be undertaken by Fine Cell Work, “a charity that specialises in the rehabilitation of prisoners through stitch work”. The livery company represents upholstery and soft furnishings, as well as funeral directing, because, when it was formed, the two trades were linked and were carried out by the same people.

The current Master of the Upholders, Roger Wates, says that the livery company wanted to commemorate its heritage by making something that will “embrace their upholstery, funeral directing, and soft-furnishing skills”.

Aidan Hart, who designed the King’s anointing screen, explains how he is often “commissioned to do work for churches which has a certain seriousness to it”. While the Circle of Life was “serious work”, he also “wanted a bit of playfulness to it”. One challenging aspect is the cohesion of the piece, particularly the colour balance of the panels. “They had to work as individual units, but also when in the circular frame,” he says.

The design process took Mr Hart, an iconographer and writer, a total of 120 hours. “There were about 25 different panels altogether, and we weren’t quite sure how to arrange them,” he says. Once complete, the panels could be displayed on a rotating wheel, which would allow visitors to view it from every angle. The final result is like “a rose window in a church”, he says.

TO ENSURE that the panels will be visually consistent, training has been provided by the Royal School of Needlework. Although the teams have “a mixture of less experienced and very accomplished needlework specialists”, and, while some were skilled in medieval stitching, none was an expert in Opus Anglicanum.

The St Paul’s Cathedral design, depicting the fire of London

The St Paul’s Cathedral design, depicting the fire of London

Each cathedral’s embroidery team has had online training and time to practise the stitches on smaller squares, with on-site sessions under way and personal tutoring provided for those who need it. So far, there have been “lots of photos and videos being sent between the different locations” to ensure that “everything will fit together at the end,” Mr Squire says.

Diana Symes, who chairs Exeter Cathedral’s Company of Tapisers, describes the embroidery style as “very precise, neat stitches that require a lot of effort and concentration”. She jokes that Mr Squire has been “very persuasive” in getting her involved with the Circle of Life project, and that she “didn’t know what [she] was saying yes to at the time”.

“Back in the Middle Ages, people who were employed or became apprentices had a seven-year apprenticeship before they could actually say that they were fully trained in Opus Anglicanum work. With our lot, we’ve only had six weeks’ training. But it was very concentrated, and the team were all very keen to learn.”

The team leaders embraced the challenge, and Mrs Symes is enthusiastic: “There aren’t that many opportunities to do something that no one has done for hundreds of years, and it seemed something that I would enjoy being part of. I used to be a teacher and actually teaching people skills which they can then pass on to others, that appealed to me a lot.”

Mrs Drummond and Lesley Fudge, the team leader for the Salisbury Cathedral panel, express similar sentiments; both are excited to be contributing to the history of needlework. Yet a project of this scale is not without its difficulties. Mrs Drummond says: “The biggest challenge is inspiring confidence in others. I think this idea that it’s got to be perfect is quite a big hurdle; so it’s about inspiring people to keep going.”

There is also the physical side of the work: “You have to really look after your hands.” But Mrs Drummond’s trick of rubbing olive oil and salt helps to “get rid of the rough bits” on her fingers.

TO STAY on target with their monthly goals, the groups meet at least once a week and work for several hours. The Salisbury team sew in the cathedral, and this has attracted “loads of visitors”, Mrs Fudge says. They allow the members of the public to “have a go at underside couching, which is one of the original 13th- and 14th-century stitches that’s quite dominant in these pieces”. Visitors also sign the guest book: “We’ve had eight-year-olds to 80-year-olds from all continents now,” Mrs Fudge says. The attention from the visitors can be distracting, however, and occasionally the team need to take their embroidery home.

While attracting more visitors and the publicity surrounding the project are welcome, a more enduring goal of Mr Squire is to foster connections between the cathedrals. One way in which this is happening, as Mrs Fudge explained, is through a WhatsApp group shared by the leaders: “One of Julian’s aims was to get the cathedrals talking to each other, and that’s what’s happened, which is nice.”

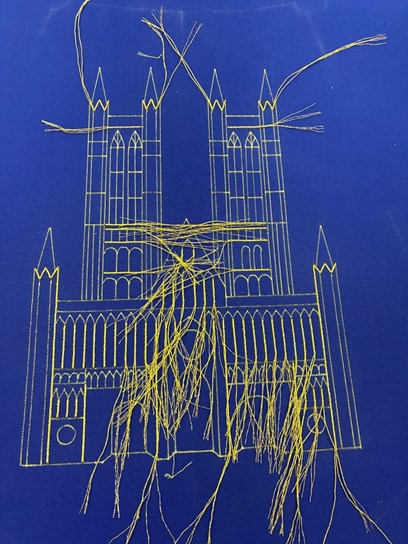

The gold outline for Lincoln Cathedral

The gold outline for Lincoln Cathedral

Mr Squire echoes this: “It’s been a very good communication project. The volunteers can benefit collectively from their learning skills and experience.”

Some of the stitching groups are visiting the other cathedrals; Mrs Symes visited the team in Salisbury. “It’s rather nice to actually get in contact with people of similar interests, and we feel a part of a much bigger collaborative project,” she says.

An equally important part of the Upholders’ vision was securing the future of sewing by preserving and passing on traditional crafting skills. Mr Hart says: “I’ve seen the need, the increased demand to train people to a high standard. So I think involvement in a project like this is a great way to light the flame.

“Discovering somebody can do something actually creates work; it creates the idea. So I think the more skilled people we have, the better. We’re finding out that we’re really good at conserving things — beautiful, old things — but we don’t really think much of making new, beautiful things in that same tradition. I have high hopes that this project will inspire people to try to do crafts more seriously.”

Each team leader I spoke to oversees a group of around four to six members of a range of ages. The oldest volunteer on Mrs Symes’s team is aged 93. Two university students had expressed an interest in stitching on the Exeter panel, but didn’t have the time to commit themselves to it. Yet, Mrs Symes does have a “young man” on board who is “very, very keen”. Like Mr Hart, she hopes that the project will inspire a younger generation. “Passing on skills is a really important and unique side of this particular project,” she says.

When Mrs Drummond became a liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Broderers, she received a booklet setting out its rules and conduct. “You are forbidden from beating your apprentices,” she jokes. “So I promise most faithfully, I will not beat any of my apprentices in the workplace.”

More information about the Circle of Life project can be found here