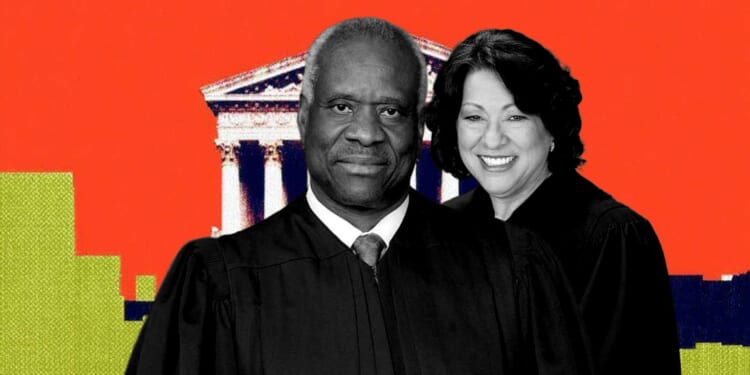

It’s not every day that you find U.S. Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Sonia Sotomayor in agreement about the destructive legacy of one of the Supreme Court’s own precedents. But such an agreement was on prominent display earlier this week.

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

On Monday, the Supreme Court declined to take up a case known as Beck v. United States. It arose in 2021 after an off-duty Air Force staff sergeant named Cameron Beck was killed while riding his motorcycle in Missouri. Beck was fatally struck by a government-issued van driven by a civilian federal employee. That driver later pleaded guilty to criminal negligence.

Beck’s widow, Kari Beck, sued the United States for wrongful death under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA). But her suit was rejected by the lower courts, who pointed to the Supreme Court’s 1950 precedent, Feres v. United States, which said that “the Government is not liable under the Federal Tort Claims Act for injuries to servicemen where the injuries arise out of or are in the course of activity incident to service.”

By refusing to hear Beck’s appeal, the Supreme Court left in place the lower court ruling against the widow.

Clarence Thomas wanted the Supreme Court to hear the case and explained why in a dissent from the denial of certiorari. “The lower courts dismissed her claim based on an expansive reading of the Feres doctrine, a ‘judicially created’ FTCA exception for injuries incident to military service,” Thomas wrote. “I have long called for overruling Feres, which lacks any basis in the FTCA’s text.”

However, Thomas added, “we did not need to overrule Feres to get this case right because Staff Sergeant Beck was not killed incident to military service at all. He was killed in Missouri while off duty and going home to eat lunch with his family.” Justice Neil Gorsuch also noted that he wanted the Supreme Court to hear the case.

Sonia Sotomayor, meanwhile, wrote separately to voice her agreement with Thomas’ unflattering description of the Feres precedent. That decision’s “atextual expansion of the Federal Tort Claims Act,” she wrote, “has garnered near-universal criticism; has caused significant confusion; and has deprived servicemembers and their families of redress for serious harms they have suffered during service to this country.”

Moreover, “like in this case,” Sotomayor wrote, “Feres has worked such harms even in circumstances far removed from the expected risks of military service. It has, for example, barred recovery for claims arising from medical malpractice, sexual assault, and (as here) car accidents, even when those harms occur on U. S. soil, bear little relation to the military itself, and just as easily could have befallen any American civilian.”

Thomas, of course, is an outspoken judicial conservative while Sotomayor is an equally outspoken judicial liberal. So it is notable that they both concluded that Kari Beck did not receive anything approaching justice for the terrible harm that her family has suffered.

But Thomas and Sotomayor did disagree about an important additional aspect of the case. While Thomas noted that the Supreme Court might have ruled in Beck’s favor without even touching the Feres precedent, he also made it clear that he would happily vote to overrule Feres if given the chance.

Sotomayor, by contrast, argued that “respect for the Court’s rules of stare decisis” led her to reluctantly “vote to deny this petition” from Beck. After voicing her disapproval of Feres, in other words, Sotomayor effectively claimed that her judicial hands were tied by the precedent. So, instead of voting to hear the case, she urged Congress to fix what the Court, in her own telling, has been getting wrong since 1950. “This important issue deserves further congressional attention,” Sotomayor wrote, “without which Feres will continue to produce deeply unfair results like the one in this case and the others discussed in JUSTICE THOMAS’s dissenting opinion.”

Sotomayor is right that Congress may modify one of its statutes in the wake of a Supreme Court ruling that interpreted the statute in a suspect manner. But Thomas is also right that the Supreme Court may do some modifying of its own when it comes to suspect past cases. On this point of disagreement between the two justices, I think Thomas has the better argument.

Ska and reggae legend Jimmy Cliff has sadly died at the age of 81. He is perhaps best known for starring in—and providing much of the terrific soundtrack for—the 1972 cult film, The Harder They Come. If you’re unfamiliar with Cliff’s music, the classic title track from that flick is a good place to start listening.

Cliff’s great 2012 record, Rebirth, is also worth a listen. Much like the unbeatable series of albums that Johnny Cash made with producer Rick Rubin in the 1990s, Rebirth features a veteran artist whose glory days were supposedly behind him in collaboration with a younger producer to make some incredible new music. For Cliff, that inspirational younger producer was Tim Armstrong, better known as a singer and guitarist in the punk band Rancid. Rebirth is not a punk record, to be clear, though it does have a sort of driving punk energy to it. Rather, it is simply Cliff still doing what he did best without missing a beat. RIP.