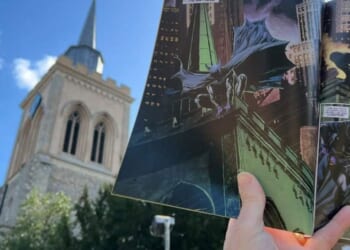

Batman can motivate you to become a better person. The emergence of The Dark Knight on Milan’s underground metro network had an extraordinary effect on the typically irritable passengers.

The fractious travellers suddenly became more charitable. When an expectant mother entered the carriage, people were significantly more inclined to offer their seats while Gotham’s champion maintained a vigilant presence.

Research by psychologists from Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore discovered that simply having a man costumed as The Caped Crusader present boosted altruism by two-thirds. The findings connect to theories of behavioural disruption, whereby novelty or surprise compels the brain to re-evaluate its environment.

Ordinarily, we navigate our days mechanically, directed by social patterns and mental shortcuts. When something peculiar – such as Batman – materialises, those patterns are interrupted.

Prof Francesco Pagnini, principal author of the study, explained: “The sudden appearance of something unexpected – Batman – disrupts the predictability of everyday life and forces people to be present, breaking free from autopilot.”

The research witnessed psychologists from Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore orchestrate 138 real-world journeys on the Milan Metro, where an experimenter posing as an expectant mother entered a packed carriage.

In the standard scenario, it was typical behaviour: merely a third of passengers offered up their seat. However, when a chap disguised as the Dark Knight slipped aboard through a separate door, charitable acts rocketed to two-thirds.

In a development befitting Gotham City itself, amongst those who gave up their seats, almost half subsequently claimed they hadn’t even spotted The Caped Crusader.

Scientists have christened this phenomenon the “Batman effect” – a momentary shock that jolts commuters from their travel stupor into the present moment, where they genuinely observe someone unsteady, pregnant, or clearly requiring assistance.

“The superhero figure enhanced the relevance of cultural values, gender roles, and norms of chivalrous help,” Prof Pagnini explained, though conventional social priming doesn’t entirely account for it, particularly when numerous helpers hadn’t consciously noticed Batman whatsoever.

Rather, it’s a matter of disrupting the routine. Most of us glide through public areas on cruise control, steered by implicit regulations and habit.

Introduce something wonderfully unconventional – a bat-eared passenger, an explosion of street performance, a piece of public artwork – and those mental shortcuts falter. Individuals reconnect, survey the carriage, and abruptly recognise what’s important: somebody who could benefit from a seat. The researchers even propose that the effect may ripple.

A handful of passengers become more alert; others catch the vibe; kindness spreads. In their words, “unexpected events can increase prosocial behaviour by momentarily disrupting automatic attention patterns and fostering situational awareness.”