I am happy to pass along this guest post from Professor Seth Barrett Tillman, which concerns how best to understand Alexander Hamilton’s analysis in Federalist No. 77. This topic is once again very timely in light of the ongoing litigation over the President’s removal power. And, once again, Tillman offers a correction to scholars who misread Hamilton. Make sure you read till the end.

***

As readers of this blog will know, there is a long-standing debate about the scope of the President’s and Senate’s appointment and removal powers. That debate has been shaped by the language of the Appointments Clause (referring to the Senate’s “advice and consent” power), ratification era debates, including Hamilton’s Federalist No. 77, debates in the First Congress, and, of course, subsequent executive branch practice, legislation, judicial decisions, and commentary.

In 2010, I attempted to make a modest contribution to this debate. Without opining either on the constitutional issue per se or on the meaning of the Appointments Clause, I argued that Hamilton’s Federalist No 77 was not speaking to removal at all—at least, not removal as we think about it today.

In Federalist No. 77, Hamilton stated: “The consent of th[e] [Senate] would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint.” 20th century and 21st century commentators have uniformly understood Hamilton’s “displace” language as speaking to “removal.” (Albeit, there have been a few exceptions over the last one hundred years.) My modest contribution was to point out that “displace” has two potential meanings. “Displace” can mean “remove,” but it can also mean “replace.” This latter meaning is, in my view, more consistent with the overall language of the entire paragraph in which Hamilton’s “displace as well as to appoint” statement appears.

Hamilton wrote:

It has been mentioned as one of the advantages to be expected from the co-operation of the senate, in the business of appointments, that it would contribute to the stability of the administration. The consent of that body would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint. A change of the chief magistrate therefore would not occasion so violent or so general a revolution in the officers of the government, as might be expected if he were the sole disposer of offices. Where a man in any station had given satisfactory evidence of his fitness for it, a new president would be restrained from attempting a change, in favour of a person more agreeable to him, by the apprehension that the discountenance of the senate might frustrate the attempt, and bring some degree of discredit upon himself. Those who can best estimate the value of a steady administration will be most disposed to prize a provision, which connects the official existence of public men with the approbation or disapprobation of that body, which from the greater permanency of its own composition, will in all probability be less subject to inconstancy, than any other member of the government. [bold and italics added]

Likewise, Hamilton, on other occasions, used “displace” in the “replace” sense. See, e.g., Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States [24 October 1800] (“But the truth most probably is, that the measure was a mere precaution to bring under frequent review the propriety of continuing a Minister at a particular Court, and to facilitate the removal of a disagreeable one, without the harshness of formally displacing him.”); Alexander Hamilton to the Electors of the State of New York [7 April 1789] (“It has been said, that Judge Yates is only made use of on account of his popularity, as an instrument to displace Governor Clinton; in order that at a future election some one of the great families may be introduced.”).

Similarly, Justice Story expressly adopted the “replace” view of Federalist No. 77. Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §§ 1532–1533 (Boston, Hilliard, Gray, & Co. 1833) (“§ 1532. … [R]emoval takes place in virtue of the new appointment, by mere operation of law. It results, and is not separable, from the [subsequent] appointment itself. § 1533. This was the doctrine maintained with great earnestness by the Federalist [No. 77] . . . .” (emphasis added)).

More recently, it appears, although one cannot be entirely sure, that Justice Kagan has adopted the “replace” interpretation of Federalist No. 77. Kagan wrote:

In Federalist No. 77, Hamilton presumed that under the new Constitution ‘[t]he consent of [the Senate] would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint’ officers of the United States. He thought that scheme would promote ‘steady administration’: ‘Where a man in any station had given satisfactory evidence of his fitness for it, a new president would be restrained’ from substituting ‘a person more agreeable to him.’ [quoting Federalist No. 77] [bold added]

Seila Law LLC v. CFPB, 591 U.S. 197, 261, 270 (2020) (Kagan, J., concurring in the judgment with respect to severability and dissenting in part). “Substituting” is, in my opinion, akin to “replace.”

However, in a 2025 article in California Law Review (at note 225), Professors Joshua C. Macey and Brian M. Richardson discuss both Federalist No. 77 and Joseph Story’s interpretation of Federalist No. 77. Macey and Richardson wrote: “Joseph Story’s Commentaries interpreted Federalist 77’s reference to ‘dismissal’ to refer plainly to removal.” There are three errors here. First, why is “dismissal” in quotation marks? It does not appear either in Federalist No. 77 or in Story’s Commentaries, at least not in the sections under our consideration. Second, Story adopted the “displace” means “replace” view. And third, the issue is not “plain.” We all make mistakes. In my view, this was a mistake on Macey and Richardson’s part.

Macey and Richardson then write: “Notably, Chancellor [James] Kent, in a letter, attributed Story’s interpretation to the original text of Federalist 77, an error which was repeated both in nineteenth-century histories of removal and by Chief Justice Taft’s law clerk in connection with Taft’s decision in Myers [v. United States].” Id. at note 225. Macy and Richardson cite two publications by Professor Robert Post in support of this view, but they do not cite any original, transcript, or reproduction of Kent’s letter. This sentence of theirs is a Gordion knot. I have made some effort to cut this knot. Let me start by saying that, as best as I can tell, Kent’s letter is from 1830, and Story wrote in 1833. So I suggest there was no way for Kent to attribute or misattribute anything by Story. Macey and Richardson are not entirely at fault. The error is in some substantial part Professor Robert Post’s, and the concomitant error, by Macy and Richardson, is their (all too understandable) willingness to rely on Post and their failure to look up Kent’s actual letter. Still, for reasons I explain below, Macy and Richardson have done modern scholars a valuable service—for which I thank them. (And, no, this is not sarcasm.)

To summarize: Macey and Richardson rely on Robert Post. Post is quoting Chief Justice Taft’s researcher: William Hayden Smith. And William Hayden Smith is quoting Chancellor Kent. We are four levels deep—so, it is hardly surprising that one or more mistakes and misstatements creep into the literature.

Professor Post wrote:

[William Hayden] Smith replied on September 22 [1925] in a letter [to then-Chief Justice Taft] that cited scattered references and concluded that “I have deduced that executive included in its meaning the power of appointment and that sharing it with the legislative was extraordinary.” Hayden Smith to WHT (September 22, 1925) (Taft [P]apers). Smith did not find much about the power of removal—the [Supreme Court] library was still looking for W.H. Rogers, The Executive Power of Removal—except that Chancellor Kent had in a letter written that although in 1789 “he [Kent] head leant toward Madison, but now (1830) because of the word ‘advice’ must have meant more than consent to nomination, he said he had a strong suspicion that Hamilton was right in his remark in Federalist, no. 77, April 4th, 1788: ‘No one could fail to perceive the entire safety of the power of removal if it must thus be exercised in conjunction with the senate.’ ” [bracketed language added] [bold & italics added]

Robert C. Post, X.I The Taft Court / Making Law for a Divide Nation, 1921–1930, at 426–27 n.58 (CUP 2024); Robert Post, Tension in the Unitary Executive: How Taft Constructed the Epochal Opinion of Myers v. United States, 45 J. Sup. Ct. Hist. 167, 173 (2020) (same). The language above is simply too elliptical to clearly understand. “He said he had”: Who is the “he” here, and whose voice is this: Kent or Smith on Kent? There is no reliable way to know what language here is Post’s, and/or what is Smith’s, and/or what is Kent’s. Nor is there any good way to tell what here is a quotation and what has been rewritten (and by whom). The one thing which is clear is that Post leaves the reader with the impression that this passage is about removal.

What to do? All we can do is to examine the next level. That is: What did William Hayden Smith write in his letter to Taft?

Here is a link to the Letter from William Hayden Smith to Chief Justice Taft (Sept. 22, 1925). Smith wrote:

In [Senator Daniel] Webster[‘]s Private Correspondence, vol.1, pp.486-7, there is a letter from Chancellor Kent upon the subject. After remarking that at the time of the debate in 1789, he had leant toward Madison, but now (1830) because of the word “advice” must have meant more than consent to nomination, he said he had a strong suspicion that Hamilton was right in his remark in the Federalist, no.77, April 4th, 1788: “No one could fail to perceive the entire safety of the power of removal if it must thus be exercised in conjunction with the senate.” [italics added] [bold and italics added]

There are two problems with the passage above, one internal to the passage, and one external to it, as quoted by Post and others.

First: the minor error. The sentence in bold and italics is from Story’s 1833 Commentaries on the Constitution—it is not from Federalist No. 77. And Kent’s letter is from 1830—so that sentence is not likely from Kent either (unless Story lifted it from Kent’s writings [which I have no good reason to suspect], or Kent was a time traveller [ditto]). The mistake here is Smith’s, and Post’s quoting Smith without explanation, and those quoting Post without examining the underlying chronological problem.

Second: the major error. The Smith passage above is the penultimate full paragraph of the letter. What has gone unreported is how Smith ends his letter. Smith, on the top of the next (that is, the last) page of his letter, wrote:

Kent went on to say that there was a general principle in jurisprudence that the power that appoints is the power to determine the pleasure and limitation of the appointment. The power to appoint, he said must also include the power to re-appoint, and the power to appoint and reappoint when all else is silent is the power to remove. However, Kent concluded that he would not call the president[]s power in[to] question as “it would hurt our reputation abroad, as we are already becoming accused of the tendency of reducing all executive power to legislative.” [italics added] [hyphen added]

This last full paragraph, which has gone unreported in the modern literature, inverts the common understanding of the prior paragraph—a paragraph which has been reported by Post and others. As I understand Kent, he is saying that absent tenure in office, the President and Senate collectively can appoint to vacant positions, and they can also appoint to occupied positions. An appointment of the latter type works a constructive removal. That’s the “removal” power under discussion in Federalist No. 77. In terms of a free-standing presidential removal power, Kent acknowledges that one has sprung from practice and by statute, and he chooses not to question the president’s use of such a removal power for political reasons. In other words, Kent, like Story, read Federalist No. 77‘s “displace” language to refer to “replace,” and not to “removal” per se or removal simpliciter.

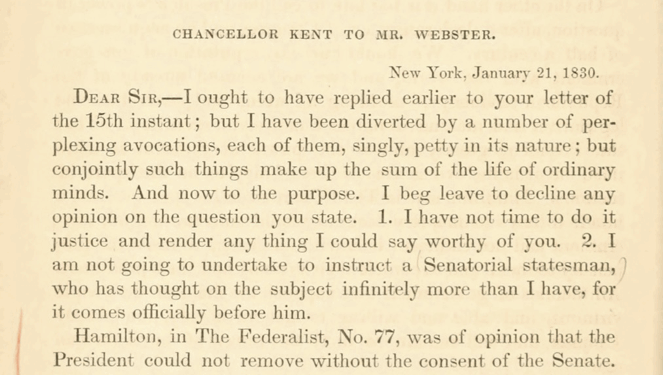

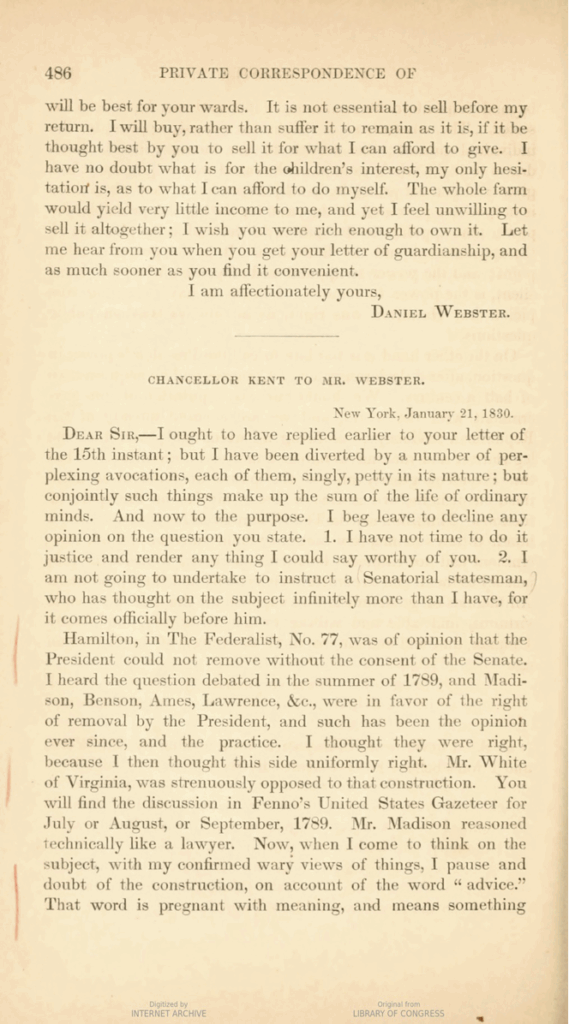

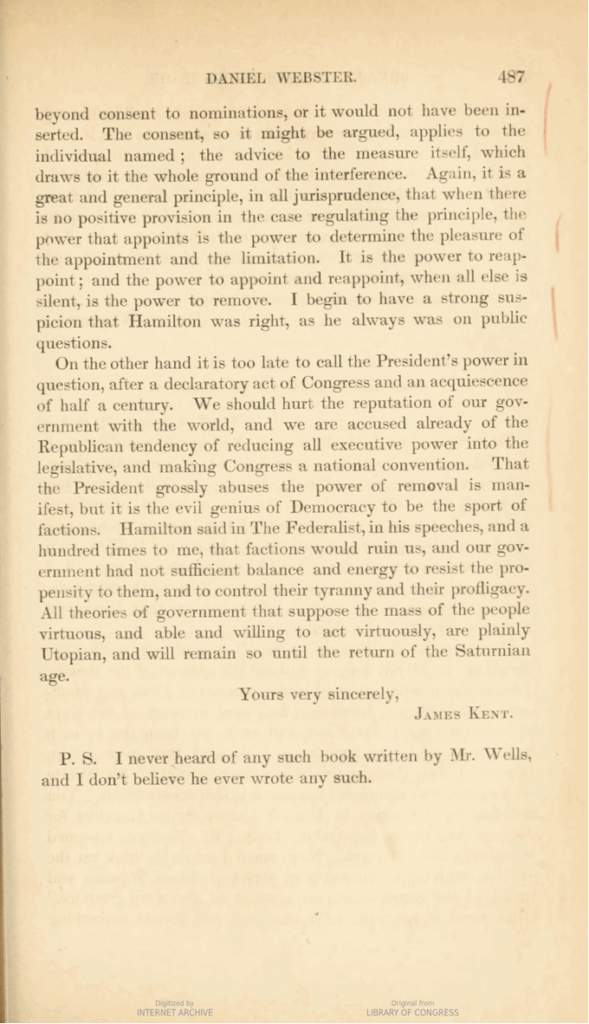

That takes us to Kent’s January 21, 1830 letter. You can read it here—at page 486 (just as reported by William Hayden Smith)—courtesy of the HathiTrust website.

Kent stated:

Again, two points here. The troubling statement from Story does not appear in the Kent letter. How could it? And the only removal power under discussion in Federalist No. 77 is the power to appoint and re-appoint, with the latter working a constructive removal. The power of the President to remove (as in a pure removal, absent any successive or subsequent appointment) arose in connection with a purported congressional declaratory act and acquiescence by congress or the public or both. That sort of removal, according to Kent, was not under discussion in Federalist No. 77. At least, that is my reading of these documents.

I thank Professors Macey and Richardson for teeing this issue up. In doing so, they have helped start a process leading to the clarification of a messy historical literature. As for Professor Post—we all make mistakes. Certainly, I am not faulting him. And I am not faulting, in any way, Professor Bailey for adhering to the traditional Hamilton meant removal in Federalist No 77 view during our 2010 debate on the issue. There is certainly evidence on both sides of the issue—that is: What did Hamilton mean by “displace”?

Still, it is troubling—more than slightly troubling—that unlike Professor Bailey, any number of academics and historians have played let’s pretend and announced, as if God, that all evidence points conclusively in one direction. Historical and interpretive questions are rarely so simple. Frequently, there is a majority and a minority view, if not more than two such views, and a stronger/better view and a weaker/lesser view. And after hundreds of years, it is difficult for moderns to identify which was or is which. But pretending that there are not competing ideas and ideals undercuts our understanding and our efforts at fair-play, and when all this is done by academics, it teaches students little more than adherence to authority, political correctness, and wokism. If academics cannot be reasonably fair in voicing disagreement, at least they should strive to be cautious—given that their favored theories may be falsified by one heretofore unknown document. Editors at journals and publishing houses who publish such one-sided materials fail to understand one of their key missions—which is to rein in the excess that comes from debate participants, who may have a fair point to make, but who have lost perspective. I know that my publications have frequently benefited from editors who advised me to moderate my language. If editors refuse to do this, than Professor Brian Frye will (and should) have his dream—a world without journals replaced by papers only “published” on the Social Science Research Network. That “is the long and short of it.” Jonathan Gienapp, Removal and the Changing Debate over Executive Power at the Founding, 63 Am. J. Legal Hist. 229, 238 n.55 (2023) (peer review); see also Ray Raphael, Constitutional Myths: What We Get Wrong and How to Get It Right 278 n.38 (2013).