A UYGHUR Christian who fled China after taking part in a Channel 4 documentary exposing the possible health hazards of nuclear-weapons testing in the country, has expressed frustration over a recent UN statement on the repression of his people.

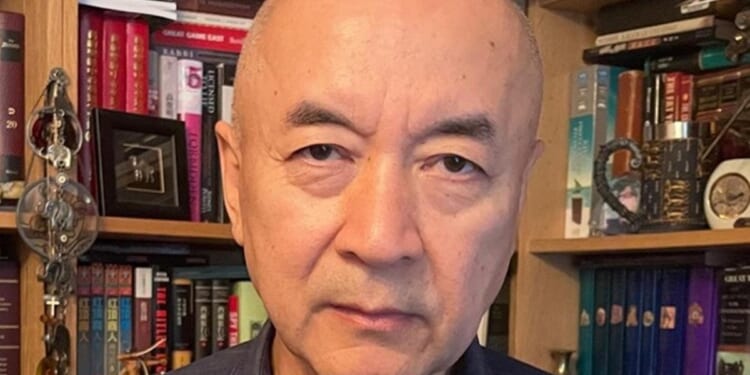

Dr Enver Tohti, who is the chief executive of the World Uyghur Christian Union, said last week that he was “utterly disillusioned” with the office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), which was “rehashing the same old tune, merely to fill space”.

On 1 October, the OHCHR issued a statement: “UN experts urge China to end repression of Uyghur and cultural expression of minorities”. It highlighted the case of the artist Yaxia’er Xiaohelaiti, a 26-year-old Uyghur songwriter sentenced to three years in prison in 2024 after being convicted of “promoting extremism” and “possessing extremist materials”. The “enforced disappearance” of Rahile Dawut, a Uyghur ethnographer and cultural scholar, was also condemned. Ms Dawut disappeared in 2017 while traveling to Beijing and has not been seen since.

The statement was issued by a group of experts who included the special rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, Alexandra Xanthaki. “These cases reflect deeply troubling patterns where cultural identity, artistic creativity, and academic work are treated as threats to national security,” it said.

Concerns about the use of “expansive and ambiguous counter-extremism laws” such as the 2015 Counter-Terrorism Law and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region De-extremification Regulation, “which appear to be used to curtail minority cultural and religious expression” were also set out.

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the plight of the Uyghurs, a minority in China living largely in a autonomous region, Xinjiang, and affiliated by ethnicity and culture with the Turkic speaking groups of modern Central Asian states.

In a House of Lords debate on China and human rights in January, the Bishop of Guildford, the Rt Revd Andrew Watson, told Peers that their situation was “well-documented. They are herded into so-called vocational skills, education, and training centres, surrounded by guards who operate a shoot-to-kill policy on those who would try to escape. Subjected to mass indoctrination, forced labour, and coercive sterilisation, it is hard to imagine a more egregious example of modern slavery in the world today (News, 10 January).

The Chinese government has defended measures such as “de-radicalisation”, which, it says, are necessary to tackle separatism and religious extremism.

Speaking to the Church Times in the summer, Dr Tohti described how he came to the UK in 1998, after fleeing China. An oncologist surgeon, he had noticed that people in Xianjiang had very high rates of cancer, and linked this to Chinese nuclear tests. The resulting documentary, Death on the Silk Road, had made him “Public Enemy Number One”.

In 2016, after securing asylum, he gave evidence to a Conservative Party human-rights inquiry into forced organ-harvesting in China. Speaking to the BBC’s Newshour on the World Service in 2018, he described how, in 1995, he had removed a liver and two kidneys from a prisoner who was still alive, in an execution ground. “At that time, I didn’t feel guilty, because I was born to such a society, brainwashed, and I also believed that, anyone labelled as the enemy of the state, it was the ordinary citizen’s duty to eliminate them.”

The “hideous practice” of organ-harvesting was “still happening”, he told the Church Times. “This industry is getting bigger and bigger”. This should be the focus of UN interventions.

Dr Tohti became a Christian in 1994. While working as a surgeon, he was inspired by the witness of a Christian patient in her late 30s who had died from breast cancer and was surrounded by fellow Christians: “At that moment, I felt I was electrified from my head through down my spine.” The woman had left him her Bible.

In the UK, he had begun attending Christ Church, Spitalfields, where he was baptised and confirmed this year. Lord David Alton and David Campanale, a former BBC journalist, are his godfathers.

In 2023, he convened the first conference of the World Uyghur Christian Union, held at St Matthew’s, Westminster, where speakers explored the Christian history of the Uyghurs, which predates the rise of Islam. Dr Tohti had been inspired by Sir Winston Churchill’s aphorism, “The farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see,” he said. His aim was to explore “the possibility and feasibility of resuscitating the Christian faith among the now predominantly Muslims Uyghurs”.

A booklet bringing together material from the conference describes the history of Christianity in the region, beginning with the introduction of the Assyrian Church of the East in the eighth century, before its decline in the 14th century and the rise of Islam. It includes the discovery of texts in the Old Uyghur language dating from the late Middle Ages, including a prayer book, and a tombstone for a Uyghur priest who died in 1324. Two Uyghur monks visited Jerusalem in the late 13th century. In the 19th century, Russian invaders discovered a small community of about 400 Nestorian Christians still living in the region. In the early 20th century, missionaries — some from Sweden — began to work there.

The conference had prompted “multiple enquiries” from fellow Uyghurs, Dr Tohti wrote in the booklet, despite the fact that “Islamic conservatism” was “seemingly becoming the main rallying political ideology for the majority Uyghurs inside and outside China”. “A mere decade ago, hardly anyone ever heard about us, the Uyghurs, a cursed, suppressed, and wronged people”.

He estimates that there are about 5000 Uyghur Christians in Xianjiang, and about another 1000 outside China. Most met to worship online, he says, too afraid to meet in person.

Dr Tohti’s hope is that the Uyghur people will return to Christianity. “Our ancestors were Christian. We enjoyed our freedom, now we lost it because we turned our back to Jesus Christ,” he told the Church Times. There is only one way to get it back: to turn our face again to Jesus Christ. If we accept Jesus Christ as our king again, then we will have dignity, and that has driven me to go in this direction.”

The Uyghurs must learn to love their fellow Chinese, he said, “because even Chinese neighbours are the largest group of victims of communism in China”.