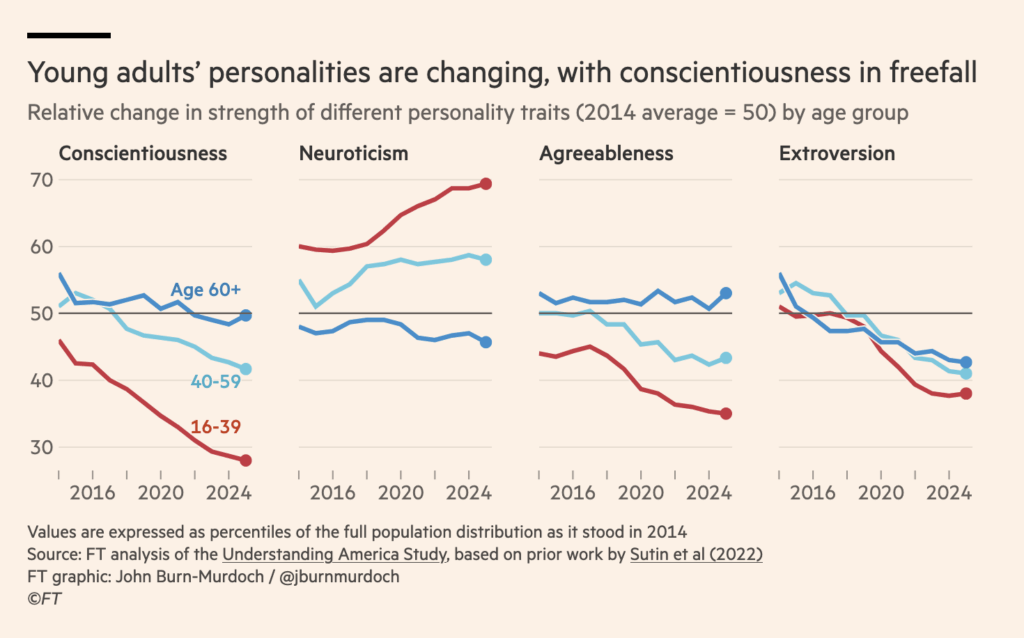

The world needs conscientious people, and conscientious people seem poised to navigate the world more easily. A huge drop in average conscientiousness could be quite a big deal. And so we’ve seen a collective freakout after the Financial Times reported on a “troubling decline in conscientiousness,” complete with a graph that seems to show young people’s conscientiousness level dropping steeply over the past decade. A chart caption affixed to the article suggested that conscientiousness was “in freefall.”

But the allegation that conscientiousness is cratering doesn’t seem to hold up. The article draws on a survey that measures conscientiousness on a scale of 9 (the lowest possible score) to 45. The youngest group of respondents, ages 16 to 39, had an average score of 35.51 in survey data from 2015 to 2017 according to an analysis of the data from the Stetson University psychologist Chris Ferguson. In 2023–2025, this age group’s average score was 33.26.

You are reading Sex & Tech, from Elizabeth Nolan Brown. Get more of Elizabeth’s sex, tech, bodily autonomy, law, and online culture coverage.

Unfounded Alarm?

Not only is that a fairly small drop, but it’s a pretty high conscientiousness score no matter which data point we take.

You would not know this from reading the Financial Times article, which not only excluded that raw data point but also included this graph:

Naturally, the article’s culprit for this “freefall” is technology. “While a full explanation of these shifts requires thorough investigation, and there will be many factors at work, smartphones and streaming services seem likely culprits,” wrote John Burn-Murdoch.

So: Is this a sober examination of technology’s psycho-social effects, or is it the latest installment in the media’s omnipresent tech panic?

One red flag is that Burn-Murdoch blames smartphones and streaming services, he bases that on the mere fact that their rise has coexisted with the alleged decline in conscientiousness.

Ostensibly, Burn-Murdoch is relying on correlation—which of course still wouldn’t mean that tech caused the drop in conscientiousness—but he does not even bother bringing in any specific correlational data. It’s something I see this more and more these days, as if we all just know tech must be the culprit and so any serious effort to back up that claim would be superfluous.

But the bigger problem here is the not the allegation that technology is causing an alarming drop in conscientiousness. It’s the claim that there’s an alarming drop at all.

SMALL DROPS IN TRAITS ASSOCIATED WITH CONSCIENTIOUSNESS

Burn-Murdoch’s data came from the Understanding America Survey, “a panel of households at the University of Southern California (USC) of approximately 14,700 respondents, growing to 20,000 by the end of 2025 representing the entire United States,” per its website. “The study is an ‘Internet Panel,’ which means that respondents answer our surveys on a computer, tablet, or smart phone.”

The first questions here should be whether this is really representative of America writ large and whether it actually portends a ongoing trend. The kind of people “who use the internet often enough to fill out internet surveys” may be different than the general population, notes Ferguson. And “who uses the internet often can differ quite a bit from year-to-year…particularly during a time frame that includes the covid19 pandemic when, for a bit, everyone was home and online, and then that gradually stopped. So there’s an obvious historical effect confound to this data.”

But let’s get into the data itself. Here’s another chart from the Financial Times article:

At first glance, those look like some pretty steep declines in self-reported tendencies to help others, be outgoing, and be trusting, along with an increase in propensity to start arguments, with all of these trends most pronounced in the youngest age group.

But look at the y-axes. These questions are measured on a five-point scale, but none of these graphs have a y-axis that starts at zero and ends at five. They’re zoomed in to represent only the small portion of that scale that experienced the shift. So while there were shifts in self-reports of these traits, they’re of a much smaller magnitude than it might seem from a casual glance. And even after the shifts, the average levels of good traits—such as helpfulness—are still pretty high and the average level of being an argument starter is still pretty low.

Based on these charts, the youngest cohort’s decrease in “is helpful to others” went from just above 4.2 to about 4.1. Its rise in “starts arguments” went from just under 1.8 to about 1.9. The drop in being outgoing seems to have gone from about 3.8 to about 3.4 (with most of the drop occurring after 2020), and the decrease in trust went from somewhere just above 4.1 to somewhere just below 3.9 (again, with a sharper drop happening after 2020).

We see the same shenanigans happening with a graph on follow-through, perseverance, distraction, and carelessness. A zoomed-in y-axis makes these drops appear steep. But look closely, and you’ll see more modest changes.

Perhaps any decline in average ratings on helpfulness, perseverance, and so on is “troubling,” even when the levels are still relatively high. But these don’t seem like shifts of a magnitude that we should find alarming, especially without more historical data to compare them to. And we certainly shouldn’t casually chalk these shifts up to “smartphones and streaming services.”

I can think of a few things—a global pandemic and the attendant lockdowns and social distancing orders, for example, or political volatility and divisiveness—that just might drive levels of being outgoing and levels of trust down a bit.

It’s also notable how vague some of these categories are. “Starts arguments”—does that mean frequently starts arguments, or just occasionally? “Starts arguments” with good cause, or just because? Someone who “starts arguments” might be socially maladjusted and prone to antagonizing strangers online, or could be someone with a strong sense of justice who found a lot to argue over in recent years,. Or maybe just a normal human being who sometimes quarrels with family members or roommates. We don’t know.

Or take “can be careless.” Again, that doesn’t sound great. But we can all be careless sometimes. Someone might label themselves high on “can be careless” without it necessarily representing anything maladaptive or concerning in their day-to-day lives.

It’s worth considering whether questions like these are measuring a serious shift in actual levels of carelessness, or simply a shift in people’s perceptions of themselves. Younger Americans have been bombarded for decades with warnings that phones and social media and so an are making us narcissistic and easily distracted and other negative things. It’s possible some of these warnings have ramped up anxiety and insecurity around these traits, leading to people with the same actual levels of these traits to rank themselves differently over time.

About that chart

Now let’s get back to that first chart, the one that appears to show a huge drop in younger people’s level of conscientiousness along with smaller drops in agreeableness and extroversion and a big rise in neuroticism and extroversion. It’s actually quite confusing what this chart is purporting to show.

Again, we have a y-axis that starts and ends somewhere in the middle of the range of data possibilities, which can give a distorted impression. But the bigger problem is that the data being presented in the first place is just plain weird.

At first, I thought the y-axis was showing percentages of people who ranked themselves as conscientious, neurotic, etc. or scored high in these categories on some sort of test. I’m sure I can’t be the only one who had this impression at a quick glance—which, of course, is all many people are going to give it.

The youngest group’s line drops from somewhere around 45 to just under 30. A drop of 16 percentage points or so in conscientiousness would be pretty big news, I imagine. But the y-axis is not showing a drop in the percentage of people in an age group who identify with the trait or test high in it.

Nor is it showing where on the conscientiousness scale the average person in an age group tested. If this is what it showed—a drop from an average ranking of 45 to an average ranking of 29—that might also be a pretty big deal. (Set aside for a moment that conscientiousness in this survey is measured on a scale of 9 to 45.) But that’s not what this chart reflects either.

You might be thinking OK, but you can read right there what this chart is measuring: the “relative change in strength of different personality traits (2014 average = 50) by age group.” To which I would respond that it’s not at all clear what that means. I’m not an idiot about data interpretation—at the very least, I’m better at it then the average news reader or social media observer—and I am finding it not at all intuitive to understand what’s reflected in this chart.

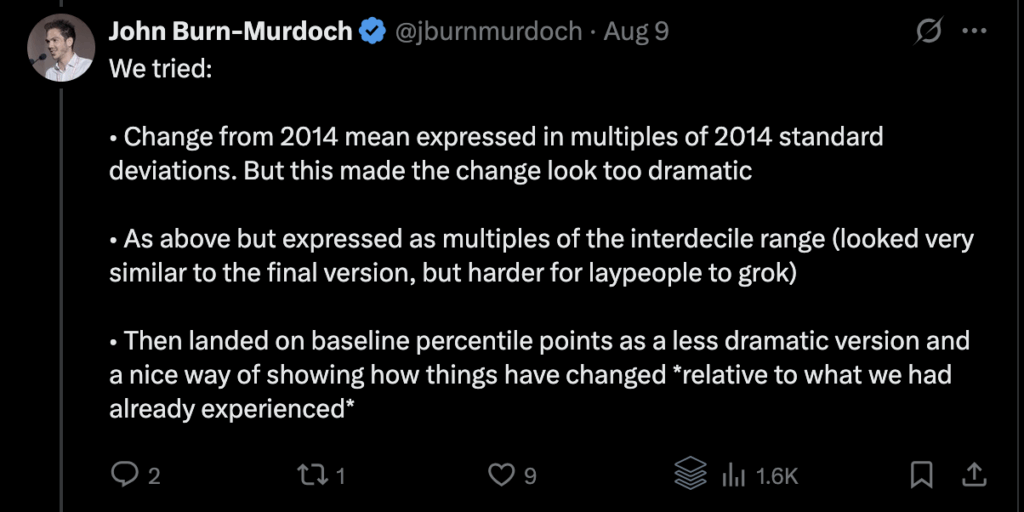

Burns-Murdoch tried to explain on X what his charts represent. “I express each age group’s average in terms of where it would have fallen on the full population distribution in 2014,” he posted. He went on to detail the ways in which his team played with the data in order to get to this way of presenting it.

If I understand correctly, the Financial Times team labeled the average conscientiousness score for all ages in 2014 as 50 and the chart shows the degree to which each age cohort fell above or below this 2014 all-ages average. In 2014, most older adults fell just a little above the average conscientiousness level for all ages and the average young adult fell just below average for conscientiousness. By the most recent data, the average younger adult fell quite a bit further below the 2014 all-ages average.

The author suggests this was more true to what the data actually show and helps people visualize it better than if they had presented it in a more standard way.

Torturing Data

Call me crazy, but this seems like a really convoluted way to present the data—and I’m not the only one who thinks so.

“That statistic is…really weird and I am not entirely sure I fully understand it,” commented the accounting professor Tyler Menzer on X. “It very much does not seem like a standard way to address the problem you were worried about.”

“Burn-Murdoch explained that he believed that presenting the raw data would be confusing for general audiences. I don’t know why that would be,” wrote Ferguson. “I think interpreting the raw data graph is pretty obvious.” Ferguson went on to suggest that the newspaper’s antics here “sound like the kind of data torturing that should make people wary of statistics.”

After reading the Financial Times piece, Ferguson decided to take a look at the actual data because he was skeptical about the idea of a massive shift. These personality variables “have a significant genetic component to them and are generally considered stable over long time frames,” he writes at Grimoire Manor, his Substack newsletter:

Some personality change can occur but, even over long intervals, these tend to be modest. I asked a couple of personality scientists, Robert McCrae and Brent Donnellan about the FT claims. Both were skeptical. To quote Dr. McCrae: “I am very skeptical.” Dr. McCrae passed my questions to Dr. Sutin who wrote “It would be nice to see the change replicated before making too much of it.”

When Ferguson looked at the raw data, here’s what he found:

The youngest age group, 39 and younger, which was the focus of all the fuss, shows mean conscientiousness score of 35.51 out of a range of 9-45 in their 2015–2017 data, the first data point available. That’s actually pretty high. By the latest data point, 2023–present, it had dropped to 33.26…actually still pretty high. That’s a drop of a mere 2.28 points.

A decline of 2.28 points in younger people’s average conscientiousness test score is easy to understand.

It’s hard to understand why Burn-Murdoch and the Financial Times wouldn’t at least also give us this number along with their spin on the data. It starts to seem like all that talk about finding a better and more clear way to present the data is code for finding a better way to draw readers to the conclusion they want them to have: that these results are “troubling.”

Is a 2.28 point drop troubling? I don’t know. It seems like the kind of point on which reasonable people might disagree. By excluding this information in favor of the method that “facilitates” a certain conclusion, the newspaper seems to be stacking the deck.

Previous Studies and Shifting Goalposts

One 2022 study published in the journal PLOS One examined personality trait shifts early and later in the COVID-19 pandemic, using the Understanding America Survey’s data. “Surprisingly, two previous studies found that neuroticism decreased early in the pandemic, whereas there was less evidence for change in the other four traits during this period,” the authors noted.

“Replicating the two previous studies,” their own research found “neuroticism declined very slightly in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic levels; there were no changes in the other four traits. When personality was measured in 2021–2022, however, there was no significant change in neuroticism compared to pre-pandemic levels, but there were significant small declines in extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.”

The authors of that 2022 study suggest this might be cause for some concern, and I’m not trying to suggest it isn’t.

But this study serves as a good reminder that there are plausible causes for personality trait shifts that are unrelated or only partially related to technology.

It also highlights how goalposts have been shifting. “For neuroticism, the anxiety and depression proneness we were all worried about until last week, young adults scores went from 22.12 to 24.03 in the same time frame, all pretty low scores,” notes Ferguson. So suddenly “we shift to talking about conscientiousness.”

Read his whole post for more details. Some people responding on X have suggested the effect size here might be more accurately described as modest rather “very small.” But the bottom line seems to be that this is nowhere near the “freefall” that the Financial Times suggests.

More Sex & Tech News

The U.S. Supreme Court won’t stop Mississippi from enforcing an age verification law for social media platforms: The court did not give an explanation for its refusal, but Justice Brett Kavanaugh did offer some thoughts in a short concurring opinion. He said that NetChoice, the tech industry trade group suing over the law, “is likely to succeed on the merits—namely, that enforcement of the Mississippi law would likely violate its members’ First Amendment rights under this Court’s precedents” and that “the Mississippi law is likely unconstitutional.” But “because NetChoice has not sufficiently demonstrated that the balance of harms and equities favors it at this time, I concur in the Court’s denial of the application for interim relief.”

Media Matters wins X-related suit against the Federal Trade Commission (FTC): The nonprofit alleged that it was being retaliated against for its unfavorable coverage of Elon Musk and X. “After Andrew Ferguson took on his new role as the Chairman of the FTC, the agency issued a sweeping CID [civil investigative demand] to Media Matters, purportedly to investigate an advertiser boycott concerning social media platforms,” Judge Sparkle L. Sooknanan points out in her August 15 opinion:

Media Matters brought this lawsuit to challenge the FTC’s CID, alleging that it is retaliatory in violation of the First Amendment and that it is overbroad in violation of the Fourth and First Amendments. Before the Court is a motion seeking preliminary injunctive relief from the CID. The Court agrees that a preliminary injunction is warranted.

A win for game companies in addiction lawsuit: “Video games are designed, marketed, and sold in a way that creates and sustains addiction in users,” alleged a complaint against myriad game developers and platforms. In a new ruling, “the court grants the motion to dismiss by Another Axiom and Banana Analytics (the ‘Developer Defendants’) and Google and Roblox (the ‘Platform Defendants’),” law professor Eric Goldman reports. “The court says that Google and Roblox win based on Section 230 [of the Communications Decency Act] because ‘the Court would have to treat the Platform Defendants as publishers or speakers of content created by third parties in order to hold them liable on any of Plaintiff’s claims.'”

New age verification laws for adult content don’t exclude websites where only a little bit of content is sexual in nature: Most such bills have applied only to platforms where a “substantial portion” of the content was sexually oriented or, as the state defines it, “harmful to minors.” Now, “newly enacted age-verification laws in South Dakota and Wyoming could create civil and criminal liability for social media platforms such as X, Reddit and Discord, retailers such as Amazon and Barnes & Noble, streaming platforms such as Netflix and Rumble, and any other platform which allows material deemed ‘harmful to minors’ but does not age-verify visitors,” says the Free Speech Coalition, an adult industry trade group. “Given the Supreme Court’s decision in Free Speech Coalition v Paxton and the expansive interpretations of the ‘harmful to minors’ standard in statehouses, website and platform operators that provide any content dealing with sex, sexuality or adult themes should be aware of the risk of weaponization of these new laws,” which took effect on July 1.

School book removal law is partially unconstitutional: Florida has been unconstitutionally removing books from schools, a federal judge ruled in a case brought by the publishers Penguin Random House, Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, and Simon & Schuster. “The suit, filed a year ago, asked the court to deem the state’s interpretation of ‘pornographic’ and content that ‘describes sexual conduct’ unconstitutional,” reports the Florida Phoenix. “By leaving these items undefined, Florida has given parents license to object to materials under an ‘I know it when I see it’ approach,” Mendoza wrote in his opinion, released last week.

Louisiana sues Roblox: “The attorney general in Louisiana has filed a child protection lawsuit against Roblox, the top gaming site for children and teens, accusing the platform of enabling sexual exploitation and failing to safeguard minors from predators,” reports WAFB/Gray News.

Today’s Image