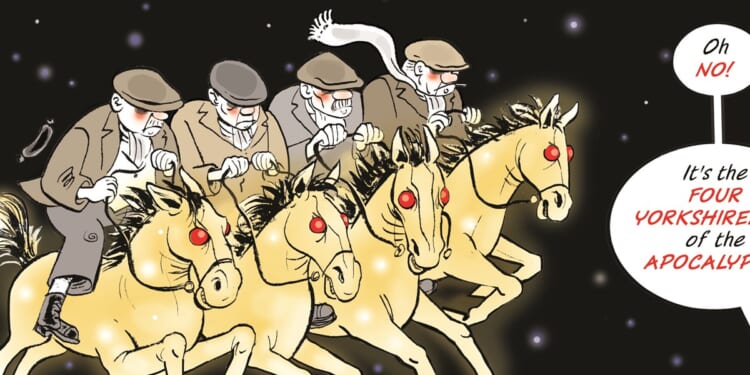

MAYBE it was a Monty Python sketch that first introduced the idea of competitive grievance. Four Yorkshiremen tell stories of their deprived childhoods, each trumping the other in exaggerated victimhood. After each sorry tale comes the derisive line: “You were lucky!” Only their grievance matters.

It is very funny — but maybe the laughter is fading now as the grievance culture threatens both politics and social harmony. As a doctor recently said to me, “Everyone is just so angry! And I don’t have a cure.”

And the doctor’s despair is politicians’ delight; for this is a tide that they can surf. Figures in both United States and UK politics amplify grievance daily among specific groups to gain and hold a following: “The elite are not listening to you! They don’t care! I’ll get revenge on them!” Dehumanisation is a wave that they can happily ride.

Nothing but a grievance culture could have created the events on 6 January 2021 in Washington, D.C.: an attempted coup by supporters of Donald Trump two months after he had lost the presidential election (News, Comment, 15 January 2021). And it is not difficult to imagine similar scenes here in the UK in three years’ time.

It wasn’t always so. In their book The Rise of Victimhood Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning discern three broad historical responses to grievance. They start with the honour/shame culture, in which offence is dealt with by direct retaliation, by blood feuds, by pistols at dawn. In honour cultures, the victim has low moral status; it is settling the score which is the moral force.

Then, in Western societies of the 19th and 20th centuries, the honour culture replaced a dignity culture. Insults or injury may cause offence, but non-violent responses are encouraged. Instead of a duel, perhaps social contact is withdrawn, or the legal path is chosen. The moral force is in the process of non-violent resolution.

But it’s all change now in our grievance culture, where the victim takes centre stage. Neither honour nor process now matters: it is the victim who is granted highest moral status, engendering what Manning and Campbell call “competitive victimhood’”.

EVEN the privileged are victims these days. Hear the cries of wealthy pensioners last year who thought that they had lost their unnecessary winter fuel allowance. As online algorithms entrap people in ever smaller communities of discontent, moral worth is defined by victimhood, by the colour of your skin (whatever the colour, you have a grievance), or fixed identity groups that think that they have the divine right to “cancel” opponents.

J. K. Rowling goes from saint to pariah in no time at all, because of her understanding of gender. Who Ms Rowling is, beyond this particular belief, is of no consequence; vicious verbal assaults and death threats multiply. Whether someone agrees or disagrees with her is not the issue. They are just watching how the grievance culture, fed by social media, operates. What someone believes in matters; but whom they hate is equally important.

It is not that grievances do not exist in the world. Paradise was lost a while back and injustice swaggers. It took brave souls to expose the Hillsborough, Windrush, and Horizon scandals. Campaigning against injustice can be a moral cause.

What is different in the grievance culture is the hell of separation, the loss of connection with others; the demonisation of those outside the circle. It doesn’t want you cheerful: it wants you consumed by rage. It offers you identity not for being yourself, but for not being someone else: “Thank God I’m not a Pharisee!”

The grievance culture baptises the victim’s self-pity, which is unwise. It offers only one prism through which to look at the world, when one prism quickly becomes stupid. Racism exists, but not everything is racist. Fascism exists, but not everything is fascist. Misogyny exists, but not everything is misogynistic. Immigration causes problems, but not every problem is caused by immigration. Single prisms suck the humanity out of our shared existence. As with the four Yorkshiremen who could not listen to one another, no one else really exists once someone steps on board the victimhood carousel.

IN THIS climate, consensus-builders are mocked as weak, while grievance entrepreneurs are celebrated as bold people who have answers.

The 1997 film Life is Beautiful is set in a Nazi concentration camp, as a Jew tries to protect his son from the horror by reframing the things that are done. What endures about the film is the attempt to reach beyond difficulty towards a celebration of human ingenuity. Here, there is the prism of anger. But here also is the prism of human spirit and joy. Two prisms are better than one.

If the quality of the journey defines the destination, people will look for leaders who live from joy rather than rage. The grievance culture is rooted in pessimism, while joy is rooted in hope and gratitude, which are better colleagues. And here’s to prophets who speak truth to power — but not hate to their followers; for hate is a false identity and an emotional cul-de-sac.

Joy is prior to grievance. Surely society can do better than the four Yorkshiremen?

Simon Parke is a counsellor and writer.