“WE ARE top of the league.” So rang out the chants at Middlesbrough FC’s Riverside Stadium recently after a start to the new season so good that it surprised even diehard fans.

New data published by the Government on Thursday of last week confirmed that Middlesbrough has, once again, come top of a different league table: the Index of Multiple Deprivation, which ranks 296 local-authority areas in England. This combined measure takes into account the interrelated aspects of deprivation such as income, education, health, crime, and housing. In Middlesbrough, half of the neighbourhoods are in the “most deprived” category, compared with a national average of one in ten. It is a similar story for our neighbours in Hull and Hartlepool.

To those of us, like me, who live in Middlesbrough, this, sadly, comes as no surprise. In one part of the town, 85 per cent of the children are born into poverty (the highest rate nationally); and it has the country’s lowest proportion of 18- to 64-year-olds able to obtain employment.

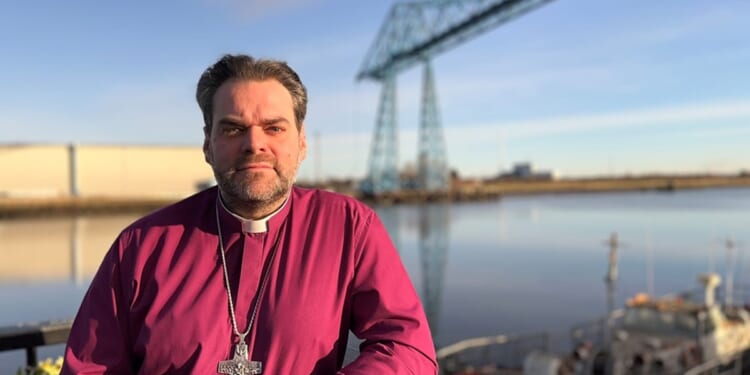

Church leaders see the effects on the lives of parishioners every day. We see (and, at times, live) the despair and, even worse, the apathy. Since arriving just over a year ago and spending time listening in each of the neighbourhoods, however, I have been struck most by the people’s gritty and resilient hope, the slightly dog-eared pride, and the sense that, even if overlooked by others, they still have some agency.

Walking around one especially challenged estate with one of our wonderful local clergy recently, I asked a young man what he liked most about living there. He spoke with pride about how, when someone died, the community raised funds to support the family. Death is always close in Middlesbrough; life expectancy reduces by a year for every mile walked from the suburbs to the centre. When support has not been forthcoming from elsewhere, the community have rolled up their sleeves and got on with it themselves.

AFTER the discovery of ironstone in the area in the mid-19th century, people came from far and wide to Middlesbrough. The town was responsible for the construction of iconic sights around the world: the Sydney Harbour Bridge was designed in Middlesbrough, built by people from Middlesbrough, and mostly made from materials mined in Middlesbrough. The demise of the iron, steel, and, latterly, chemical industries has left a deficit of money — and, even more importantly, of opportunity and aspiration. But, as often in life, we are living in more than one story at a time.

Twice a year, in partnership with Middlesbrough College, I host a breakfast for 70 civic, community, political, charity, and faith leaders from across the town to deepen relationships as we seek to address these issues. The mood among these leaders is realistic, but far from downbeat. Alongside challenges, a new narrative is also forming: new green industries are starting to thrive; jobs are (far too slowly) being created; the largest brownfield site in Europe has now been cleared, and building work is under way; the changing demography is bringing greater racial diversity (especially in churches); and even the Turner Prize is being hosted here next year.

The churches of the town see pain and encourage hope. Almost every Sunday this term, I am baptising and confirming new Christians in the area, often by the dozen, sometimes at two or even three confirmation services a week. Most stories of faith start in knowing dignity, love, and practical care through one of the dozens of ministries that parishes in the town faithfully and sacrificially operate, day in and day out. Each confirmand is invited to share beforehand some of their story; so often, it is in the midst of deep pain in life that people have come to know the love, life, and hope that Jesus Christ alone offers.

One of the most common features that new Christians speak about is that they have felt seen by God in a world that has overlooked them. As Hagar said to God amid her despair, “You are the God who sees me” (Genesis 16.13).

Last Sunday, at baptism and confirmation services in two communities with deep pockets of need, we explored Jesus’s words in the Gospel reading: “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the Kingdom of God.”

THE Church of God needs places such as Middlesbrough, not to make us feel good about ourselves because we are helping others, but because renewal and revival always start in the places of greatest need. We should not seek first to change places such as Middlesbrough, but to be changed by them and by the stories of how God is at work. Mission and ministry in places of deprivation is hard, and yet the blessings are often far greater, too.

We cannot do this alone. Clergy posts in 94 per cent of Middlesbrough parishes would not be possible without Lowest Income Communities Funding from the national Church. We are in the midst of discerning a big vision, for which we will be seeking Strategic Mission and Ministry Investment Board funding next year. If your parish has large reserves, feel free to send them over; but, more than money, we are praying that God will send labourers.

Like so many areas that are closer to the top of the Index of Multiple Deprivation, there is a high vacancy rate for clergy in the area. Posts can be hard to fill, because sometimes it can be easier for eyes roaming the job pages to look south rather than to have their sights lifted.

As the Middlesbrough saying goes, “Shy bairns get nowt.” If you are looking to know blessings in ministry, if your faith is audacious and tenacious, then come on in: the water in the north-east is lovely.

The Rt Revd Barry Hill is the Bishop of Whitby, in the diocese of York.