BY CHRISTMAS 1942, the 50,000 or so Allied troops in Changi had already been prisoners for ten months, surviving on a starvation diet of rice, vegetables, and scraps of fish. And they were beginning to be sent off by their Japanese captors to work as slave labour on projects such as mining, or in factories and shipyards.

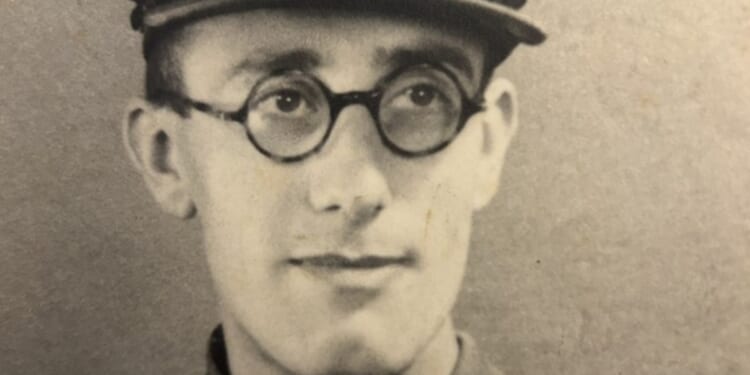

My father, Eric Cordingly, a rector in the Cotswolds, was now an army padre attached to the 18th Division of the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers. He was determined to celebrate the Christmas message of hope for so many of the displaced men in his “parish” who, he knew, were very homesick. He had created a church out of a small abandoned mosque, which he called St George’s. It attracted a loyal congregation.

IN HIS diary, he described how the men had enthusiastically decorated the church: “Below the dome of St George’s the atap [palm-]roofed verandas twinkled with hanging lamps made from half shells of coconuts and inside a bully beef tin filled with palm oil and a floating wick. Then nearer still at the entrance stood a Christmas tree, a local imitation of our English fir reaching to the roof.

“Reflecting the lights from little lamps fastened to the branches were stars, small horse-shoes, all shapes and sizes of tinfoil covered objects. Then inside the church itself the pillars were covered in ferns and along the low wall between the arches stood pots of coloured flowers.

“Both Dutch and British troops went out with trucks to collect all these decorations. But one’s gaze was centred on the chancel — here, in a mass of candlelight, the altar was emphasised as the focal point. The flowers and feathery green ferns enhanced the setting for the Celebration of Holy Communion that was to take place at midnight.

“On Christmas Eve on the padang, a two-acre green patch almost opposite the church, a stage was erected. Behind this, in curved rows, was a massed choir of a hundred and the theatre orchestra. It was around this platform that at half past eight three thousand men were grouped for a concert of carols. From the platform the impression I received was that of a vast sea of faces, and so the familiar carols went up in mighty roar.

“A Dutch naval officer gave a moving speech and depicted the blackness of our present life, he told of the black hour of the Dutch folk living in countries under the heel of the enemy. Then three men came forward and poured oil into a bowl and lighting this with a torch he spoke of the light of the Christmas message, a light which shines so brightly now because of the blackness that at present surrounds the world. It was all very impressive. I gave a short precis of the ceremony in English and then said some prayers and gave the Blessing and so began our celebration of our first Christmas as prisoners.”

THEN 800 or so men gathered at his own church for midnight eucharist. “Just after midnight, in an atmosphere that was real and moving, those familiar words ‘O come, let us adore him’ were sung, quietly hushed, and rising as a prayer after the final words of the Prayer of Consecration. The altar rails filled as men in turn knelt and received communion. The shabby green uniform of the Dutch army was emphasised in these rows of khaki-clad figures. Present too were those maimed in battle, an empty sleeve, a stump of a leg.

“Outside the moon was reflected on the shiny surface of the palm branches and in the ear vibrated the persistent hum of the crickets. Streaming back to their billets were men who had recaptured a glimpse of our Christian Christmas. Peace on earth to men of good will, that was the prayer in each person’s mind, as was the thought of our own homes which are the successors of that first little Family, simple prayers but so real.”

THE camp cooks managed miraculously to provide special meals for the day. “For the first time we were able to drink coffee with tinned milk and in the evening we ate a most superior dinner. Ten scraggy cockerels carefully nursed for months, preceded by soup and followed by a fair imitation of plum pudding. It was the right colour and had dates in it.”

As the year 1942 drew to a close, he reflected on what they had experienced. “We are starving, not melodramatically but slowly, scarcely a third of the camp is fit enough for work. I am convinced an impartial observer would say that life centred round the church is maintained and, indeed, on the increase. Spiritually then, I believe we are in fair fettle. Bodily we are not in such flourishing condition. The suntan hardly hides the poor physical condition.”

LITTLE did they know what was to come. The work parties continued to be sent away, and my father was sent up with F Force to the River Kwai on Easter Day 1943, where the men laboured on building the Thai/Burma Railway under brutal conditions. The Far East POW fatality rate was nearly one third.

When, 25 years later, he reflected again on these years, surprisingly he called them “the most wonderful time of my life in spite of the grim and hungry times. One had the opportunity, as a priest, of doing something which is denied to us in our ordinary lives here at home. For once and for three and a half years the thin veneer of civilisation had been stripped from men. We were all down to bedrock. One saw people as they really were. I know that the services we shared in together were utterly real and sincere, and I suppose it was because we were, for a while, utterly real and sincere.”

Louise Reynolds published her father’s diaries, and the illustrations by his fellow-prisoners, in a book, Down to Bedrock, in 2013. Eric Cordingly was consecrated in 1963 to be Bishop of Thetford.

A version of this article appears in the parish magazine of St John-at-Hampstead.