THERE is a lightness of touch to Sir Chris Bryant’s autobiography which almost belies the horror of the abuse that he encountered as a young and vulnerable boy, struggling to come to terms with his sexuality.

Prodigiously talented academically, verbally, theatrically, he would appear, on the surface, to have sailed through independent schools (on scholarships), to the institutions of Oxford, the Church of England, and Westminster. His talents attracted mentors and abusers: with an alcoholic mother and a father unable to cope, he was deeply vulnerable.

He writes about his mother’s long descent into alcoholism, and his reckoning with the complex emotions that it provoked it him.

Sexual abuse stalked him from prep school onwards: he describes an evening with the founder of the National Youth Theatre (NYT), Michael Croft.

Croft groomed him with dinners and conversation, before taking him back to his house. What followed, Bryant writes, left him feeling “like a 16-year-old whore”.

It’s an experience — and it only happened once, he emphasises — that he has struggled to speak of before. It is revealed for the first time in his new book, A Life and a Half: The unexpected making of a politician.

“I still feel ashamed of it, which is why I’ve never spoken publicly about it,” he writes.

He adds quickly: “I don’t feel damaged by what happened,” and he went on to act in Croft’s productions, without any repeat of the abuse. Yet, today, he says, the act of recording the audiobook “made me realise there is a lot about shame and guilt and anger, that really came back to me when I read it”. Recalling the events of his early years, they “were both strengthening and affirming while sort of challenging”, he says.

Croft died in 1986. His funeral was held the day after Bryant’s ordination. In a surreal twist, Croft’s will stipulated that the funeral should be conducted “for nowt” by Bryant. So, his first service as deacon was to lead a huge funeral at which the pews were full of the stars of stage and screen.

THE abuse of power did not stop as he moved out of the NYT, but continued in his ministry in the Church, in which he was ordained deacon after studying at Cuddesdon. In one passage, he recalls being invited to a bishop’s palace for an interview, “only to find myself racing around a grand piano in his living room, trying to escape his clutches. . . He eventually gave up, panting and clasping at his pectoral cross as if it were a life support machine.” The bishop in question is still alive “and not in his full mind”, he says; so he has chosen not to name him.

Others he recalls with great fondness — and sadness — as he describes gay clergy denying themselves love and affection in an effort to live under the guidance provided by the document Issues in Human Sexuality, finally dropped by the House of Bishops this summer from the discernment process for ordination.

He says now that it was the experiences, and the sadness of some of these gay clergy — going away once a year to the resorts of Mykonos or Sitges and spending the rest of the year alone — which made him certain that “that is not what I wanted for myself. I wanted to live my own life and not live in that shadow.” He resigned his position in the Church when he turned 30, and moved to London.

The decision was informed by his then fiancée — he was twice engaged to women in his twenties — telling him after a night together: “Christopher, you do know you’re gay, don’t you?”

His own experience of abuse left him unsurprised at the Church’s crisis over its past safeguarding failures. “I think every institution I’ve ever been involved in has tried to protect the institution more than the potential victim. Every single one of them.” The Church “was just about the worst”.

He acknowledges that significant reforms have been made since his time in both the National Youth Theatre and in the Church. “The NYT now has a whole safeguarding structure. The Church . . . well, it’s an institution founded on a rock. And rocks are notoriously hard to move.”

SIR CHRIS BRYANT made headlines in 2016 when, after the Anglican Primates’ vote to sanction the Episcopal Church over its consecration of gay bishops, he tweeted: “I’ve finally given up on the Anglican Church today after its love-empty decision on sexuality. One day it will seem as wrong as supporting slavery.”

He describes this today — with the same wry and deprecatory tone that runs through the book — as a more of a “trial separation”. “I love the fact that it exists, and I feel I have more of a relationship with my faith than I do with the Church. I don’t go to church very often. Though I went to communion on the morning of my civil partnership. My husband went for a manicure.”

The book ends with his election as an MP for the Rhondda, 24 years ago, but his final words are drawn from reflections during his two years in curacy in High Wycombe. It is perhaps fitting for a man whose newspaper headline so often begin with the phrase “ex-priest gay MP”.

Being an MP and a priest are both callings that mean that “people talk to you, and sometimes about the most intimate things in their lives as well. So that is the most phenomenal privilege, both callings,” he says.

“I always think it’s hilarious that sometimes I get called ex-gay vicar. And I want to say: the gay thing is coming along quite nicely — it’s just the vicar thing.” He still intends to claim his right to be buried as a priest, “the right way round”, with head towards the altar.

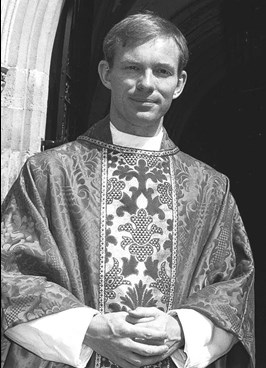

from the bookChris Bryant as a curate, demonstrating his adeptness at “looking pious in posh frocks”, as the caption in his book puts it

from the bookChris Bryant as a curate, demonstrating his adeptness at “looking pious in posh frocks”, as the caption in his book puts it

It is unusual for a government minister to publish a book while in office, but, in his case, the book was agreed before the election. His ministerial post does prevent his talking about his brief in any way in this interview, although I raise the Listed Places of Worship grant scheme anyway. He was the minister to announce a year-long reprieve for the scheme earlier in January, but it is no longer part of his brief, which covers tourism and data protection.

He says that he has no involvement now in the discussion over whether it should continue, though mentions that, as with his understanding and experience with parish churches, he also has sympathy with theatres that are also struggling financially.

On assisted dying, which was a conscience vote, he is happy to talk about the reasons behind his change — from abstaining at the first vote to voting for it at the second. His own recent cancer experiences and the death of his father both had an impact on his decision. He was diagnosed in 2019 with skin cancer — stage three malignant melanoma — which metastasised in his lung in 2024.

“I was told in 2019 that my chances of living a year were 40 per cent; so that brings you up against the possibility of death. And I’m not frightened of it: it’s fine. So that started it. And also my dad, who had frontal-lobe dementia. He wanted to go. And, you know, he refused food and drink and stuff towards the end. And then you have to make difficult decisions about whether to force-feed somebody, and all that made me think, in Desmond Tutu’s words, death isn’t the worst thing that can happen to a human.

“I always feel a bit disturbed that the Church’s interest in the body politic seems to be about sex, sexuality, abortion, and assisted dying rather than all the things Jesus was interested in.”

In another narrative style twist, his own treatment for cancer has been led by Dr Mark Harries — son of Lord Harries, the bishop who ordained Bryant deacon in the diocese of Oxford. Lord Harries is a “decent and serious human being”, who offered to officiate at Sir Chris’s wedding to his husband, Jared Cranney.

He tweeted last month that he is cancer-free — for now, though the treatment has left him needing a new hip.

He ends our interview with a quotation whose author he can’t remember — he thinks it might be Rowan Williams — “There are only two rivers you can’t dam up. One is spirituality and the other is sexuality.” And despite the abuse, the challenges, the struggles and rejections, his exuberance does seem unstoppable.

He finds his motto in a slightly gauche bit of wedding advice that he gave a young couple, as a young curate: “Never be content to stand still. Always hope to change for the better.” The couple, he says, were abashed — he was embarrassed — but he stands by it.

A Life and a Half: The unexpected making of a politician by Chris Bryant is published by at Bloomsbury £25 (Church Times Bookshop £22.50); 978-1-5266-8091-4.

The book is reviewed by Richard Harries here.