Olivia Barker White, CEO and co-founder of Kids Club Kampala (KCK)

OLIVIA BARKER WHITE first visited Uganda in 2007, during a gap year that she and five other young people had embarked on with a Christian charity.

When she arrived, she was asked to teach boarding-school pupils “whose English was better than mine”, she says. Frustrated, and with time on their hands, the six made friends locally, including with 22-year-old Sam Wambayo, who took them to the slum communities, where nothing could prepare her for “children running barefoot through open sewage; picking through rubbish tips looking for food”, she says.

The six and their Ugandan friends started bringing in footballs, play-parachutes, and sweets, “to play games with the kids, engage with them, tell them that Jesus loves them; do some fun Bible stories”. The idea of providing Kids Clubs was born.

Mrs Barker White and one of the other gap-year participants, Corrie Fraser, tried in vain to interest British charities working near by in addressing the needs that they saw. Angry with God, she sensed God telling her: “I am doing something, and I want you to join in.” She says that Ms Fraser and Mr Wambayo felt a similar call.

Mrs Barker White switched the place that she had at Manchester University from geography to international development. Student friends helped to fund-raise for the clubs, and she began returning to the slums in her summer holidays.

Jean BizimanaKids Club Kampala, in Uganda

Jean BizimanaKids Club Kampala, in Uganda

The longer-term needs of children there, such as access to education, quickly became apparent. Her Ugandan friends registered Kids Club Kampala Uganda as a charity in Uganda in 2010, and she and Ms Fraser registered Kids Club Kampala in the UK in 2011. “I was a student, and I had no idea what I was doing. But I had a lot of spare time, and lots of enthusiastic people. I do wonder, if I was doing that now, now that I’ve got three kids and a mortgage. . .”

After graduating, Mrs Barker White worked in international development in the private sector, and she and Ms Fraser ran KCK in their spare time. In 2013, Cosmopolitan named the pair, then both 24, Ultimate Global Champions in their Woman of the Year awards, for having helped some 4000 children.

The award prompted Mrs Barker White to give up her job and move to Kampala. Initially, both women worked as co-directors to extend the charity’s reach. After initial support from friends and family, both became employed part-time as UK directors in 2015, when Mrs Barker White moved back to the UK.

Since those early days, “We’ve brought on other staff, and last year we raised over £1 million.” Ninety per cent of the fund-raising is from donors in Britain; the community work is done by 58 staff and 60 volunteers in Uganda, many drawn from local churches that the charity is in partnership with, backed by a UK team of eight staff, 20 volunteers, and ten trustees.

Ms Fraser stepped back from her position in 2018, but still has ties to the charity, while Mrs Barker White now works full-time as CEO in the UK office.

The charity’s work now includes education (help with school fees and related costs), child protection (counselling, teaching children about their rights, and help into foster care or kinship care), and poverty reduction (vocational training to strengthen vulnerable families). The Saturday Kids Clubs also still run.

This year, the team have also taken on the running of another charity, in the UK, the Mango Tree, which helps vulnerable children across East Africa with access to education.

Setting up a charity, Mrs Barker White says, has its highs (including seeing the impact on the ground) and its lows — such as a break-in at the charity’s office in Uganda, when computers, laptops, and security cameras were stolen. Such items, she says, are “almost impossible to fund-raise for. Sometimes, you feel like you take two steps forward, one step back.”

Being agile as an organisation, and listening to the people they work with, has been vital to their survival, and has reaped its rewards: during the pandemic, when schools in Uganda closed for two years, KCK converted their classrooms into a foodbank and provided some 45 million meals, earning the Ugandan team recognition from local- and national-government officials.

There are constant challenges to overcome for any charity. One currently affecting KCK is the impact of aid cuts from the UK and US governments, which has meant that children they work with who live with HIV no longer have access to free anti-retroviral medication. For now, at least, KCK has been able to use some of its own funds to buy the medication.

Another looming challenge is the threat of unrest linked to forthcoming presidential elections. “It’s not always a nice linear ‘You do this thing; it has this direct outcome,’” Mrs Barker White reflects.

On a personal level, sometimes she has felt “overwhelmed and fatigued with the constant need and responsibility. Sometimes, I have no choice but to switch off. I’ve got three little ones. . . Sometimes you just have to decompartmentalise.” These days, she goes to Uganda about once a year. Mr Wambayo is the charity’s Uganda country director.

Passion, flexibility, and supportive people to collaborate and hold discussions with have stood the charity in good stead, Mrs Barker White says. Her advice on setting up a charity would be: “Find other people you can do it with. It can be very isolating.”

Mrs Barker White is a trustee of the Small International Development Charities Network (SIDCN), which she finds a useful space for talking through issues such as working cross-culturally and “decolonising” development. She admires Tearfund’s model of working through local churches and communities.

Will it ever be time to move on? “It’s something that I think about, and ask God about, because I don’t ever want to become stuck,” she says. Increasingly, she has felt God speaking to her about challenging the Church in the UK about what the Bible says about caring for the poor here, including immigrants, she says.

John Kirkby, founder of Christians Against Poverty and the Isaiah 61 Movement

WHEN Dr John Kirkby decided that he wanted to help people who were struggling with debt, he had plenty of experience to draw on. By his early thirties, he had already made and lost a great deal of money, at the cost of his marriage and the family home, and had ended up in “huge” debt.

He became a Christian after being invited to church by a pastor to whom he had rented a house. “Because of my experience of the finance industry and my entrepreneurial get up and go, I managed to sort my finances out myself, got myself back into a career, and [became] pretty successful in the next four years,” he says.

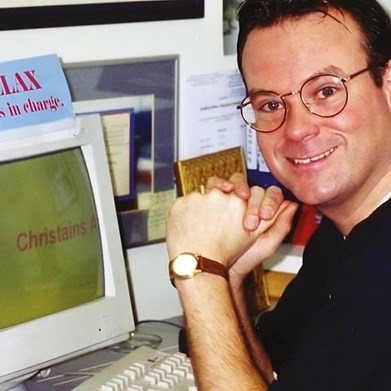

John Kirkby at his computer in 1996, when he founded CAP

John Kirkby at his computer in 1996, when he founded CAP

He ran a secure lending division for a large plc, negotiated with his creditors, and paid off much of his debt. He also sorted things out with his ex-wife, “became a good dad to my two girls, and [at church] met Lizzie, my wife now of 30 years”.

In 1996, weeks before he was to marry Lizzie, “Something in me clicked, or snapped.” He realised “I want to help the poor, and I want to share Jesus, because what’s happened to me can happen to others.”

He began the charity Christians Against Poverty (CAP) with £10 and a computer. “My idea was to go out on the streets of Bradford and find other people like me, and help them get out of debt, but also introduce them to church.”

Devising a new way of combating poverty meant that it was hard to attract donors to support it. Rather than give material help, Dr Kirkby (and, in time, the team that he built up) would set weekly budgets with clients, agree repayment plans with creditors, and go to court to stop homes from being repossessed. His team would also offer to pray for clients and invite them to church.

The model worked for the people whom they were helping, but not for Dr Kirkby and his team. “At the end of the month, we used to see how much money we’d got, and we used to divide it by need.” Dr Kirkby and his wife were in a “desperate financial personal situation. . . Even when our first daughter was about to be born, we were losing the house.”

Dr Kirkby was not paid on time for 13 years. “If I’d have known the price, I wouldn’t have done it,” he reflects. But, other than give up, and let down the families they were working with, he says he cannot see how they could have avoided the cost.

What kept him going was the support of family and friends, and seeing transformation in people’s lives. After about a year, “We had people in the church who found faith, we had people feeding their kids, we had homes not repossessed,” he says with excitement.

Aware that the need was far wider than Bradford, he saw the potential to grow by opening volunteer-run centres in churches. After ten years, there were 50 CAP centres; after 2, there were 500 and 5000 volunteers, and he had exported the model to Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.

“We could have done much more — or less relational — debt counselling, which would have seen more people go debt-free,” he says. But, between 1996 and 2021, when Dr Kirkby stepped down from the charity, CAP had helped up to 250,000 people around the world get out of debt, besides helping thousands of people to find faith and be drawn into a church.

Dr Kirkby was appointed CBE by the late Queen (a CAP supporter) and received an honorary doctorate from Bradford University, and various Sunday Times awards, including Business Leader of the Year. Accolades are “lovely”, but their real use is in assuring government officials and potential donors of a charity’s integrity, he says, as, for example, when they set up in the United States in 2019.

In 2020, approaching 60, Dr Kirkby found himself stirred to respond to a new sense of calling. In March 2023, “gobsmacked” by what he calls the “apathy” in churches about talking about Jesus to friends and family, and inviting them to church, he and a small team launched the Isaiah 61 Movement (i61m), to help churches to “change culture and be more Jesus-sharing”.

Stewardship, the fund-raising site for Christian charities, said of i61m: “The UK Church is facing an existential crisis. Most Christians simply aren’t sharing their faith in any meaningful way. It’s the massive elephant in every church room. If we don’t arrest this, our churches will slowly die. i61m uses a unique combination of technology and group accountability to help Christians put action to intention, through a journey of ‘sharing life, faith & Jesus’.”

What advice would he give to others feeling stirred to start a charity? “Have your fear of man surgically removed,” he jokes, having received discouraging comments from other Christians at the start of both charities.

Running a charity well, by building robust systems that ensure that you are building the culture that you want in your organisation, and knowing how much of your income is covered by regular giving, is vital, he says. “Every week, for 25 years, we were on the numbers: no excuses because you’re a charity.” As for the financial precariousness, he advises knowing your own appetite for pain and risk.

Fiona Spargo-Mabbs, founder and director of the Daniel Spargo-Mabbs Foundation

FOR Fiona Spargo-Mabbs and her husband, Tim, there was no question that they would set up a charity in memory of their son, Dan (Feature, 3 June 2016). The 16-year-old died after taking the drug ecstasy at an illegal rave in west London, one Friday night in 2014. By Monday, he was gone.

In hospital, as their son lay unconscious, they felt that the tragedy was “so avoidable” and asked themselves: “What could we do?” and “How many other parents weren’t as well-armed as they needed to be?”

Praying for him there, Mrs Spargo-Mabbs, a teacher, recalls: “I had a sense that God was furious that Dan had died, and that this was part of a bigger battle that God was engaged in.” She adds: “I was never angry with God. . . God and I were angry together.”

The couple wanted to sound an alarm on the dangers of drugs to teenagers. The next day, when reporters came knocking, they invited them in for an impromptu press conference. When Dan’s story was in every national newspaper the next day, the idea for the charity was born.

Days later, they registered as a charity with Companies House. Friends fund-raised through sponsored events. “We committed ourselves to walking through every door that we felt God opened to us,” she says.

While police pursued two young men in conjunction with supplying the drugs (one would be sentenced to five years, one would be found not guilty), an inquest into why Dan had died was still months off. Unable to focus on “anything that wasn’t Dan”, Mrs Spargo-Mabbs set about understanding what drugs education was available, and what was still needed, returning to her work part-time in adult-education management for a while.

Factor3Fiona Spargo-Mabbs, founder and director of the Daniel Spargo-Mabbs Foundation

Factor3Fiona Spargo-Mabbs, founder and director of the Daniel Spargo-Mabbs Foundation

The following year, she and an experienced PSHE teacher piloted a drug education lesson in two schools in Croydon; in 2016, Mrs Spargo-Mabbs began being paid by the charity. Today, ten staff now work in nearly 700 schools, about one quarter of which are in Scotland (run largely through peer-influencers and parents trained by the charity). In the charity’s first ten years, nearly 190,000 young people had been reached by the workshops.

Meanwhile, Dan’s drama teacher suggested that a play would communicate well to young people. Mr and Mrs Spargo-Mabbs commissioned the playwright Mark Wheeller, who crafted his script from interviews with Dan’s family and friends. The play, I Love You, Mum: I promise I won’t die, had its première in 2016 (Arts, 8 April 2016), and in 2022 was made a GCSE drama set text (along “with Shakespeare and J. B. Priestley”, Mrs Spargo-Mabbs says, smiling). It has been performed in schools, colleges, and theatres in the UK and Australia.

The charity now has behind it a mix of regular and one-off giving from individuals, people undertaking challenge events, and two corporate donors: the Artemis Charitable Foundation, the charitable arm of Artemis Investment; and Ecclesiastical Insurance’s Benefact Trust.

Mrs Spargo-Mabbs was appointed OBE in 2023 for services to young people. She sits on the Government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. She also set up, and chairs, the national Drug Education Forum, to pool best practice among drug- education providers.

What would she advise someone considering setting up a charity? Ask yourself “What can I do?”, he says. “I knew about education.” Then, “Surround yourself with people that can do the stuff you can’t do.”

She has learnt the importance of a strong board of trustees: it is OK to draw on family and friends, she says, “but make sure that that board is people that have got the right skills.”

Be clear about your objectives, she says. Filling in the Memorandum and Articles when registering on the Companies House website is “a very boring, formal thing, but it’s really, really important. That’s how you set up what you do.”

On starting a charity after a tragedy, she notes that her husband, Tim, and her, and Dan’s elder brother, Jacob, “were on the same page” about doing it, which, she believes, was important.

Mr and Mrs Spargo-Mabbs also found it helpful to consult drug-education charities and two other charities started by bereaved parents: the Chris Donovan Trust and the Mizen Foundation.

They also valued having a supportive community, and people praying for the charity from the start. None the less, they opted not to become a faith-based charity, “because of the ethical dimensions of our specific area of work, and not wanting there to be any barriers set up in reaching anyone”.

When is it time to move on? Mrs Spargo-Mabbs says: “At the moment, we both need each other too much. . . There may come a point where the charity’s grown to a size beyond my skills.” A good question to ask yourself, she concludes, is: “Would I be appointed to this role?”

Paddy and Carol Henderson, founders, Trussell

TRUSSELL (as the Trussell Trust now prefers be known), the charity that became synonymous with emergency foodbanks in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, actually started in 1997, as a project for street children in Bulgaria.

In 2000, on a fund-raising trip back to their then home in Salisbury, Paddy and Carol Henderson received a call from a mother in their area who was struggling to afford food for her family.

Not having worked in the charity sector in the UK before, they spoke to teachers, church leaders, and health workers across Wiltshire, and identified extreme pockets of poverty “in what looks like an affluent community”, Mr Henderson recalls.

They started the first foodbank in the UK in their garage, providing three days’ emergency food to people who had been left without enough money to live on.

From the outset, they were amazed by people’s willingness to help. “We realised, if each person in Salisbury were to donate one tin of food, we could support people facing hunger across the community,” Mr Henderson says. In one of their first fund-raising efforts, “by mid-afternoon on the first day, people had donated just over one ton of food.”

Trussell trustees sought to develop a team who shared the ambitious vision “to end hunger in the UK”, Mr Henderson says, organising the trust’s foodbank development on a “petal system”, and building outwards; their second foodbank was not far away, in Swindon.

In 2004, making room for further growth, Trussell launched the Foodbank Network, to enable churches and other groups to open their own foodbanks.

TrussellPaddy and Carol Henderson, founders of Trussell

TrussellPaddy and Carol Henderson, founders of Trussell

The Hendersons opted to make Trussell a Christian-based charity, “because we are committed Christians and . . . during times of crisis in our work, we were always grounded by two things: faith and hope”. Churches were also well placed to get on board, because they are often at the hearts of their communities, and could provide “venues, volunteers, leadership, donations, and more”, Mr Henderson says.

They did “a lot of praying along the way”, and had to learn to “trust God in everything — even when we had nothing coming in”.

They were able to draw on their professional experience developed in the British Army: Mrs Henderson’s administrative skills and Mr Henderson’s organisational skills, as well as their shared experiences while working for charities such as Tearfund, and running a range of emergency food projects with emerging churches in Armenia and Bulgaria.

What personal characteristics do you need? “A strong tenacity to keep going, even when it’s hard; and hope,” Mr Henderson says.

To anyone considering setting up a charity, they counsel: “Think twice, because it isn’t easy. It is gruelling work. You will probably be underfunded, and therefore need to do a range of jobs yourself, like marketing, fund-raising, and personnel management, that can be really daunting. This was our experience at the start.”

When is it time to move on as a charity founder? “If you are in a leadership role, it is easy to get burned out, and you need dedicated time to recover and refocus,” Mr Henderson says.

They were trustees of Trussell until 2014, and the network of foodbanks grew as the need grew. “We did not feel we had the skills to go to the next level, and thought it was the right time to pass the baton.”

The couple moved to New Zealand, and, eventually, “once we understood our community”, felt called to start a new organisation. “We then established a small charity volunteering for a church with a range of mini projects,” Mr Henderson says.

In the period April 2024 to March 2025, Trussell’s foodbank network operated out of 1711 centres across the UK, providing roughly two-thirds of all emergency foodbank provision in the UK. Trussell’s work now also includes advocacy, research, and campaigning about the root causes of foodbank need.

Serial charity founders, the Hendersons also set up a Christian counselling agency in Salisbury, the Lightship Christian Counselling Service, which is still running. The work in Bulgaria has grown, and the charity, now called House of Opportunity, runs throughout the Balkans.

trussell.org.uk

houseofopportunity.org

lightshipcounselling.org

For official advice on setting up a UK charity, visit: gov.uk/setting-up-charity