ANDRÉ TROCMÉ, the Calvinist pastor of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon during the Second World War, made this riposte when Marshal Pétain’s Vichy officials ordered him to reveal the Jews in his town: “We do not know what a Jew is. We only know men.”

At a time when Gentiles feasted on expropriated Jewish wealth, and handed over neighbours to feed the Nazis’ genocidal machine, Trocmé stands out as a beacon amid wartime France’s moral darkness, as I discovered researching my book Ninette’s War. This covers the experiences of Ninette Dreyfus, a Parisian teenager whose relatives were dispatched to death camps, never to return.

At least 2000 Jews were saved by Le Chambon’s Calvinists. They included Nicole Nadal, Ninette’s playmate during their Riviera exile. Nicole, later the wife of the industrialist Serge Dassault, hid, using false papers, after the SS arrived on the Riviera in September 1943. Two months later, her father was denounced and arrested, but nuns hid his wife and children in an orphanage, from where Nicole and her brother were shepherded to Le Chambon. Her father, however, was transported to Auschwitz in a convoy of 1147 Jews, including 221 children, and was not among the 72 who survived.

The heroism of Trocmé’s flock was the largest single act of Christian rescue in wartime France, a country where newspapers encouraged Gentiles to denounce Jews. But this came at a price. Trocmé’s second cousin, Daniel, a teacher, was killed for protecting his pupils.

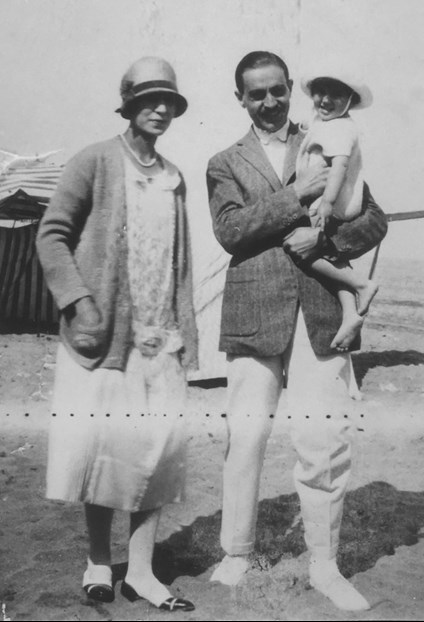

Ninette, Edgar Dreyfus, and Viviane Martinez, Cannes, 1942

Ninette, Edgar Dreyfus, and Viviane Martinez, Cannes, 1942

Roman Catholic bishops in France welcomed Pétain’s dictatorship after France was defeated in 1940. Many were unreconciled to France’s secularist Third Republic, and cheered when Pétain restored religion to the classroom and replaced the 1789 slogan of “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” with “Work, Family, Fatherland”.

Bishop Jean Delay, of Marseille, where Ninette spent a year, having fled Paris as the Germans advanced, told Pétain: “God is using you . . . to save France.” One colleague, Emmanuel Suhard, Archbishop of Paris, remained Pétainist to the end, despite the evidence of genocide. In July 1944, as Allied tanks thundered towards Paris, Suhard attended the state funeral of Pétain’s Jew-hating propaganda minister, Philippe Henriot.

As Trocmé’s actions showed, however, Calvinists recognised Nazism’s unchristian nature early on. From 1685 onwards, French kings had persecuted them; so they tended to empathise with a persecuted minority. When policemen handed Jews to the SS, people recalled the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572, when Catholics embarked on mass assassinations.

PASTOR Marc Boegner, the Calvinists’ leader, was an early opponent of Pétain’s policies of exclusion, expropriation, internment, and deportation, and his followers were disproportionately represented among Christians who were helping Jews to flee to Switzerland. They included Madeleine Barot, the head of La Cimade, a refugee organisation, who would use the home of Annecy’s Calvinist pastor as her staging post.

Martha Hartmann was Ninette’s headmistress in Marseille. A Pentecostalist, Hartmann welcomed Jewish refugees, including Ninette and her sister, Viviane, but her opportunities to resist Vichy were limited. When Pétain banned Jewish teachers, she had to fire Ninette’s maths teacher, Odette Valabrègue, one of “the Pope’s Jews”, an expression derived from the time when medieval popes protected persecuted Jews in the Comtat Venaissin, then papal territory.

Ninette and Viviane at Le Manoir at Pau

Ninette and Viviane at Le Manoir at Pau

Valabrègue then scraped a living tutoring Jewish children, and survived to be reinstated when France was liberated. Her pupils included the children of Lucien and Margot Vidal-Naquet. When the Germans reached Marseille, they deported the couple, but the children survived; Pierre became a historian dedicated to challenging Holocaust denial.

Cannes was Ninette’s second home in exile. Jew-hatred was rife, but the Riviera’s Protestant clerics, Edmond Evrard and Pierre Gagnier, in Nice, and Charles Monod, in Cannes, were early defenders of Jews. After Cannes officials banned Jews from opening a synagogue, they held ceremonies in private homes, but the police raided one home; so Monod provided a school hall for services.

Later Evrard, Gagnier, and Monod supplied false baptism certificates, actions for which Monod was prosecuted. Meanwhile, his cousin, Annette Monod, “the angel of Drancy”, cared for Jews in Paris’s very own concentration camp, most conspicuously after the infamous Vél’d’Hiv round-up. The Vél’d’Hiv was a stadium where 8160 Jews — including 4115 children — were held in dire conditions for six days before being deported and killed.

IF CALVINISTS saw the light first, many Catholics joined them later. After Le Juif Süss, a French version of a Goebbels film, was screened in Marseille, Jew-haters bombed a synagogue. This was a wake-up call for Bishop Delay, who wrote to Marseille’s chief rabbi expressing “deep indignation at the criminal and cowardly act”, and saying that Catholics’ “moral sense cries out against such an outrage”. Pétain’s officials censored the letter, but its contents were smuggled abroad and published.

In 1942, when more than 40,000 Jews were deported, including thousands handed over from the then Non-occupied Zone, the Archbishop of Toulouse, Jules-Géraud Saliège, spoke out. On 23 August, Saliège’s sermon described “children, women, men, fathers and mothers treated like a lowly herd”, and family members separated and “shipped off to an unknown destination”. His message was: “Jews are men, Jewesses are women . . . they are our brothers. . . A Christian cannot forget this.”

Paul Rémond, Bishop of Nice

Paul Rémond, Bishop of Nice

Closer to Ninette’s second home-in-exile, the Bishop of Nice, Paul Rémond, ran a rescue network whose members included Louise Palet, headmistress of a school attended by Ninette’s sister.

When SS Jew-hunters arrived in Cannes, Rémond supplied fake baptismal certificates so that she could hide Jewesses in her school. Ninette’s relative, Francine Fould, whose family had constructed some of France’s grandest battleships, benefited from a Rémond certificate stating that she had been baptised in Algeria.

Rémond also provided rescue facilities to two Jews: Moussa Abadi, a Syrian actor, and Odette Rosenstock, a Parisian doctor, telling them, “A child’s life is sacred to me.” He gave Abadi an office, and recruited Rosenstock as a social worker. In total, they saved 527 children by placing them with families or in Catholic institutions. The cost was heavy: Rosenstock was deported to Auschwitz. She was kept alive as a doctor, and ended the war in Belsen, where, unlike Anne Frank, she survived, but five children she tried to help, and two social workers, were also deported. None survived.

RÉMOND came close to sharing their fate. Alice Mackert, an SS interpreter nicknamed “Alice la Blonde”, was a leading Riviera Jew-hunter. Following a tip-off, she visited Rémond with two Jewish-looking children, begging him to “hide them as you have hidden so many others”. Fortunately, Rémond had been warned about this woman with hair “too blond to be believed”; so he said he had no facilities. As a result, Rémond lived to host Charles de Gaulle at a Te Deum service, as Ninette observed first-hand when he toured the Alpes-Maritimes in 1948.

Four years previously, Ninette’s family, whose pre-war life had been one of luxury and privilege, were hiding outside Pau, in the Pyrénées, protected by Pierre Barthe, a horse breeder, and his devout wife, Madeleine. Conscious that the Barthes saved their lives, Ninette, in later life Lady Swaythling having married into Britain’s Jewish aristocracy, persuaded Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial institution to have the couple declared Righteous Among the Nations, a title awarded to Gentile rescuers.

In her naiveté, Madeleine told Ninette’s mother, Yvonne, “The whole of Pau is praying for you.” Yvonne responded, “I would prefer if the whole of Pau did not know about us.” Although the family’s papers were expertly forged, Yvonne was fearful because wartime Pau was home to Basques enthused by Hitler’s promise that they could be an autonomous “Volk” within his New Order.

Ninette, and her mother and sister, witnessed what could have been their fate one afternoon when they encountered a roadblock. “People were screaming and pushing,” Viviane recalled. “Some people were pushed into tarpaulin-covered lorries.” Trying to look “indifferent”, the women retreated. Viviane could feel the sharpness of Yvonne’s fingernails as she clutched her hand, tense with “fury and horror”.

Yet Pau was home to anti-collaborationists such as Sister Andréa Costedoat, a nun who ran a private school. Ninette did not enrol in Costedoat’s school because this might have invited difficult questions. Instead, she did her lessons at Costedoat’s home, until travelling there seemed dangerous.

Monks also opposed Vichy Jew-hatred long before the Catholic hierarchy. In the Alpes-Maritimes, Fr Marie-Benoît, a Capuchin friar, ran an escape line to Switzerland. Then, in 1943, he worked with the Italian-Jewish banker Angelo Donati on a mass exodus. Seeking support from Ninette’s father, Edgar, a bank chief executive until Pétain evicted Jews from French banks, Donati sought to evacuate tens of thousands of Jews to Africa to save them from the SS. Donati escaped when premature disclosure of the Italian armistice provoked the Germans to march into the Alpes-Maritimes, but his secretary was denounced and killed.

IN LYON, the Jesuit Fr Pierre Chaillet produced the clandestine Catholic journal Cahiers du Témoignage chrétien. “France, beware of losing your soul,” one pamphlet declared. Another described Hitlerism as an ideology of domination, arrogance, and lies, one that showed contempt for man, for weakness and kindness, for justice, truth, and faithfulness.

Denise Schoenfeld, as a child, with her parents Maryse and André, in Normandy

Denise Schoenfeld, as a child, with her parents Maryse and André, in Normandy

Ninette’s relative Denise Schoenfeld owed her life to Parisian Jesuits. Her father, a disabled Great War veteran arrested in 1941, was told in 1943 that he would be deported, but could bid his family farewell. It was an SS trick. When he arrived home under guard, the Germans arrested his wife and deported them both. Denise, however, escaped down the building’s service staircase and fled to a Jesuit community, where she was given papers describing her as Denise Ségalas, in honour of the Catholic writer Anaïs Ségalas.

That Denise should turn to the Jesuits was no accident, because Jesuit priests hid many children under false names. This was dangerous work. One Parisian theologian, Fr Michel Riquet, was arrested after encouraging his students to rescue Jews and was dispatched to a concentration camp.

For a year, Denise hid in a convent, not knowing the fate of her parents or grandmother, deported in the last mass transport from France four weeks before General de Gaulle entered Paris and took part in a Te Deum at Notre-Dame. Only after VE Day did she discover that her parents and grandmother had been rendered as ashes in Auschwitz.

Ninette’s War: A Jewish story of survival in 1940s France by John Jay is published in paperback by Profile Books at £11.99 (Church Times Bookshop £10.79); 978-1-80522-067-1. Holocaust Memorial Day is 27 January.