If you love walking, Stockholm was built just for you. Spread across 14 islands linked by bridges, the city brims with waterfront promenades, ferries gliding through inlets, the whir of bicycle wheels, and pedestrians spilling into lively café-lined squares.

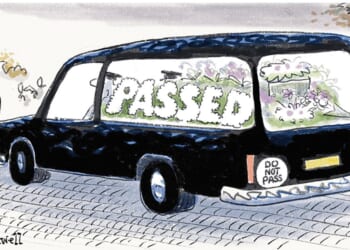

Not long ago, traffic clogged the bridges between the city’s neighborhoods. Despite a world-class public transit system and a relatively small population, Stockholm’s congestion rivaled that of London and Paris. For decades, city leaders proposed fixes, but nothing stuck until 2002, when Sweden’s parliament approved congestion pricing.

The idea was simple: Charge a small fee for vehicles entering and exiting the city center to reduce traffic, improve accessibility, and clean the air. At the time, two-thirds of Stockholm’s residents opposed it, dismissing it as unnecessary or even a “catastrophe.”

Then came the pilot program in 2006. Almost overnight, traffic through the congestion zone dropped 20 percent, air pollution fell by 12 percent, and public transit ridership soared. All it took was the equivalent of a $2 fee.

When the seven-month trial ended, traffic bounced right back, making the benefits impossible to ignore. In a citywide referendum, Stockholmers voted to make it permanent.

Today, the toll is dynamic, shifting with demand. Peak hours cost about $3, midday dips to around $1.15, and daily charges are capped at roughly $14 in summer and $10 in winter. There’s no charge on weekends, public holidays, or nights—or during July, when the city empties out for vacation. Cameras at entry points scan license plates, and bills arrive monthly.

The transformation has been dramatic. Inner-city traffic is down by half. Buses run faster and more reliably. Ferries shuttle commuters between islands. Cycling has ballooned, from just 1 percent of trips in the 1980s to 32 percent on a sunny day now. The roar of engines has been replaced by chatter from outdoor cafés. Streets once jammed with cars have been turned into pedestrian zones, while others have dedicated bus lanes or protected bike paths.

As Jonas Eliasson, one of the policy’s architects, explained, paying for road space might feel odd at first, until you realize that it’s “the same thing when you pay more to take a flight during the busiest travel periods or to pay more for electricity during peak hours.”

Millions in annual revenue from the fees are reinvested into bridges, sidewalks, bike lanes, and transit infrastructure. Most importantly, it has shifted habits and mindsets: People plan trips to avoid peak changes, choose alternate modes of travel, or skip unnecessary driving altogether.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline “How Stockholm Tamed Traffic.”