ANNE SMYTH, the widow of John Smyth, the man thought to be the most prolific serial abuser to be associated with the Church of England, has spoken for the first time publicly, in a Channel 4 documentary broadcast on Wednesday.

“I hated what he was doing,” she says. “My inability, or my whatever it was, didn’t let me intervene. I just didn’t know how I could. I practised too often not facing up to things that were wrong; and so I began not to see things as wrongly as they really were. Because I think more of the horror of it is clearer to me now. Although I stayed by him all his life, all my life, it was such a relief that he died.

“I want with all my heart to say I am so sorry; I am ashamed of myself.”

The two-part documentary, See No Evil, was produced by Passion Pictures and includes interviews both with survivors of Smyth’s abuse and with his family. His children, P.J., Fiona, and Caroline, describe a materially privileged childhood, but one in which they felt fearful and uneasy about their father.

Fiona, who says that she “hated” her father, recalls: “I don’t ever remember not being afraid. I would hide behind Mum’s skirts.” Having spent much of her childhood in Zimbabwe and South Africa, she had begun investigating her father’s history upon returning to England. “I really wanted Dad to be exposed. I wanted there to be some kind of reckoning.”

The documentary features Mrs Smyth recalling her first meeting with her future husband on holiday in Norfolk, when she was 16. This is in contrast to the chronology set out in Keith Makin’s review of Smyth’s abuse, which describes the couple meeting when she was in her early twenties in Swanage. At least two of the godparents of their children were young men who were also his victims, including Andy Morse — one of the documentary’s interviewees.

PASSION PICTURESThe Smyths on their wedding day

PASSION PICTURESThe Smyths on their wedding day

Many of the beatings administered by Smyth took place in the garden shed of the family home, Orchard House, to which he would bring boys from Winchester College, often for Sunday lunch. Mr Makin writes that Mrs Smyth “knew of the abuses and assisted with dealing with the physical consequences of them. She gave the victims bandages and ointment, as well as adult-sized nappies, to help with the stemming of bleeding.”

One victim recalled how Mrs Smyth had explained: “We’re conscious that this can result in some blood, we don’t want you to have to remain like that, we don’t want to be found out, we don’t want you to have blood on your underpants or your clothes or whatever, so if you put one of these on each buttock for the next few days, that will prevent any blood getting onto your clothes.”

One contributor to the review described how, when he visited the Smyth home, Mrs Smyth had told him that her husband wanted to see him while he was in the bath. Her presence in the bathroom had “made the event feel legitimate”. It also records that, while on holiday, the couple asked that their children’s “misdemeanours” be recorded in a “red book” so that Smyth could “administer suitable punishments for them on his return”.

Mrs Smyth’s account of her actions in the documentary is given in response to questions from P.J. and Fiona. P.J., who was beaten brutally by his father, asks: “Looking back, I don’t understand why you didn’t bring some sanity to the decisions he was making. . . Where were you? Were you unable?”

In her response, Mrs Smyth speaks of realising “something I didn’t realise at the time, and that was that he was two different people, sometimes even more. And, when another side of him took control, it was shattering; and I didn’t know how to break into that difficult person.”

She recalls her husband telling her that some of the boys who were coming to Sunday lunch were “really keen to learn more about the Christian life, but, being young teenagers, a lot of their behaviour is probably not as good as it could be, and I think they would appreciate being dealt with”. He had specified “just having a whack or two”. She had pointed out that the boys were not his own children and questioned whether they would really want such treatment, to be told by Smyth that they did.

“And I said, ‘I don’t really go for that and wouldn’t like to be involved.’ ‘Oh no, no, no, you wouldn’t be involved at all.’” She recalls giving boys cotton wool and ointment.

“Although I knew about this and didn’t approve, I struggled to know what to do about that,” she says. “It was difficult. My faith had shown me and taught me that you have to focus as much as you can on the good. I was married to him, and I knew I had to love the man; just keep going, don’t dwell on the things that are so awful. But it was hard, a very hard task. I wish I had had the wisdom at the time and the strength to have faced him myself.”

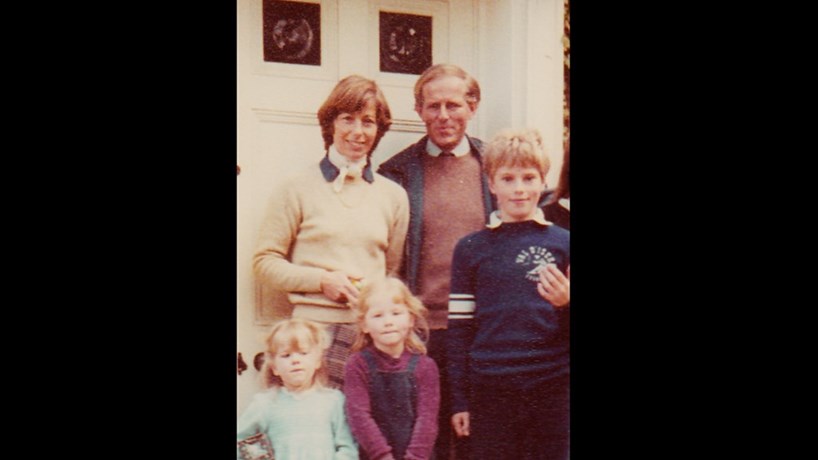

PASSION PICTURESThe Smyth family

PASSION PICTURESThe Smyth family

In response, Fiona describes her mother as “Dad’s first victim”. She was “the perfect Christian wife because she never stood up to him”. Mrs Smyth recalls that Smyth’s temper “was frightening. If something wasn’t quite right, he blasted me, and I would stay silent often.”

The survivors interviewed are Andy Morse, Mark Stibbe, “Graham”, and Jason Leanders. Mr Morse describes how Smyth, a “father figure”, still appears in his dreams. The shed was “a hell hole”, he recalls. Graham describes “diabolical” beatings, while Mr Stibbe recalls pretending to faint, fearful that he would die. It was Mr Morse’s attempted suicide that prompted the Ruston report on Smyth’s abuse, produced some 43 years ago.

The documentary also explores Smyth’s abuse in Zimbabwe. Jason Leanders, who attended Smyth’s camps there, describes Smyth breaking a bat on him.

In a message to survivors, Mrs Smyth says that she is “desperately sorry that I wasn’t strong enough to stand up to him, just to say to him ‘why don’t you just stop all this?’”

Mr Stibbe says in the documentary that he does not know of any victims who blame Mrs Smyth: “I fully and unconditionally forgive her for what happened all those years ago.”

This week, Graham praised the documentary, which had been done, he said, “with great sensitivity . . . I want people to watch it and weep.” But he remained unconvinced by Anne Smyth’s account, saying that she was “much more culpable” than had been intimated. While PJ had “shown contrition and turmoil” and was “first and foremost a victim” his mother’s account did not “ring true”.

See No Evil, on Channel 4, is scheduled for 9 p.m. on Thursday and Friday, but available now to stream.