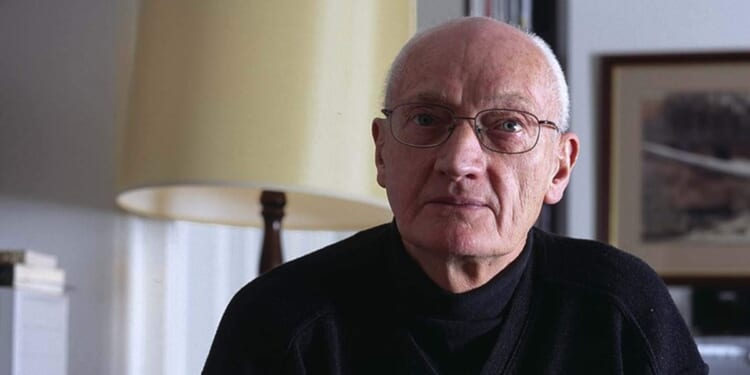

AT THE age of 91, Richard Holloway has written a book, Last Words. This is his 34th: quite a lot of words. Are these really his last? “You can never trust writers,” he admits. “At my age, I should shut up. I’m not sure I have anything much left to say. But it feels like the final book.”

We talk about this and his current preoccupations in a telephone call from his Edinburgh flat, where he lives with his wife, Jean, who, among other things, is a hymn-writer and bereavement counsellor.

Holloway has always been a storyteller and someone who has reflected on his past. And, in Last Words, he revisits his tough, poor, but loving upbringing in Random Street, Alexandria, West Dunbartonshire, in the Vale of Leven, surrounded by ancient hills. There is a valedictory, elegiac quality to the book.

“I’ve always had a melancholic side to my nature. Melancholy is not sadness,” he says. “It’s a kind of mood you fall into when you consider the passingness and transience of things. Our lives just flow towards the end, but you look back on memories, your parents, your schooldays — all of that, and, as I get older, I spend more time doing that. . . And this is a grateful kind of looking back, I guess, at the way my life went, people I owe a lot to, especially my parents, my mother . . . a reflection on what has been, what feels like the final run.”

But this is more than a memoir. He can’t help worrying at old scars, old questions. He returns to the 18th-century polymath Gottfried Leibnitz, who asked: “Why is there something rather than nothing?”, and to what potential answers to this might mean in terms of the nature of God, the invention of religion, and the prospect of the afterlife. His conclusion: “The brave answer is that we just do not know.”

These issues have always troubled Holloway, and he has had a long time to think about them. He has been engaged full-time in matters of the soul for longer than almost anyone else I can think of. At the age of 14, he packed a suitcase containing, among other things, his first ever pair of underpants, to go to Kelham House, a residential Anglo-Catholic seminary for poverty-stricken would-be priests and monks.

His adult ecclesiastical journey took him, among other places, to Ghana, the Gorbals, Boston in the United States, Oxford, and Edinburgh. His time in the Gorbals was a game-changer: “The Gorbals was a challenge in all sorts of ways. It was intensely poor. . . [I] got into rent strikes and things like that, and it put me in touch, I suppose, with the Jesus who challenged the excesses of power, so that the practice of my religion ceased to be a piety and became a kind of political action; and that was a big transforming element.”

Later, when he was at Old St Paul’s, Edinburgh, he attempted to blend Anglo-Catholicism with the Charismatic movement: “It was crazy and funny, and we imagined that we were speaking foreign languages when we were just gabbling enthusiastically, but it was a shot in the arm at the time when maybe Christianity needed a wee kick.”

In an uncomfortable poacher-turned-gamekeeper position, Holloway ended up as the Bishop of Edinburgh and the Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church. Here, his views on ethical issues got him into hot water: “When you move from religion to ethics, that is when it becomes very dangerous.”

He wrote a book, Godless Morality, “because it seemed to me that religious morality tipped people into a persecutory frame of mind, whereas if you kept a questionable transcendent out if it, and looked at the best way humans could run their affairs, and inter-react with each other, you very often came up with a post-religious thing. . . It got me into quite a bit of trouble. There was a kind of heresy trial about it, because it was reckoned that you couldn’t have morality without God. Well, it all depends on what your God is.”

The book was condemned by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, who called it “unacceptable”. Ultimately, in 2000, at the age of 66, Holloway resigned. Leaving the post enabled him to be more candid about his concerns for religion generally and the Church in particular. It turned him into an agnostic. “We are afflicted with the need to understand, the need to ask questions, to figure out meaning. With us has come that questioning that produced religions — all 10,000 of them. But the trouble with the answers that religion presents to itself, or believes that it has had revealed unto itself, is that they all tend to fall out with each other.”

He concludes: “I suppose that prompted me to a kind of holding to things with a kind of lightness, because you never know when you might have to drop it, move on to something else. I’m still very grateful for what these inspired choices brought me, but not taking any of them as absolutely true, because we just don’t know.”

His gentle, post-enlightened liberalism, and his support for women and the LGBT+ community, brought him as many plaudits as brickbats. But stepping away from the Church helped to cement his position as a kind of apostle of doubt. His mantra-like assertion that the opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty — that faith and doubt are essential partners — encouraged a great many of his readers.

“I think that religion is an art. I think it’s one of the things we’ve invented to try and explain ourselves to ourselves” He writes: “What our souls really need are sacraments, those outward and visible signs that wordlessly mediate our longing for the mystery we call God, even if there was never a God there to be mediated in the first place. . . These empty and abandoned holy places capture the enigma of our longings in ways that words can never accomplish.”

In these last words, he asks whether there is a God, and what the hereafter might be like. God’s existence is still open to question for Holloway, because he cannot reconcile a loving God with the ever-presence of cruelty, pain, and death. He writes: “Only a heartbroken God will do for us. If there is any reality behind that word ‘God’, how could it not be in constant grief over the massive fuck-up it created when it came up with us?”

So, what lies ahead? He does not welcome the idea of eternity: “At some point, I realised I didn’t want to go on and on and on for ever. And it’s more than just a low boredom threshold. I just cannot imagine the tedium of what eternal life would be like. . . And it seems to me that if you believe that death is it, it will make you look on life and the lives of others as something to be enjoyed and cherished.”

He continues: “I hope that death is it. I love my family, but I don’t want to meet them on the other side. . . I can’t conceive of that, don’t want it. I’ve had an astonishing life, I was gifted with it, but when it’s over, I want it to be over, I don’t want to have to kick in and start all over again. . . I’ll be sad to leave when I leave. I hope and expect that will be it.”

If Holloway has doubts about God and the hereafter, what makes him a Christian, albeit an agnostic one, is what might best be best described as his discipleship of Jesus: “The parables of Jesus — especially the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son — reach something very deep about the way religion can make us dangerous persecutors of others. I think that the Good Samaritan, in particular, because the Samaritan . . . would have been hated as a heretic. . . That challenge to persecutory thinking is something that I think was profoundly there in Jesus, especially in his parables: something we can still read and get benefit from, without necessarily transcendentalising them.”

He sees Jesus as “an artist, a prophet”. He says: “It takes prophets to nudge humanity on. It’s prophets who say ‘Well, why shouldn’t women have the vote? Why should there be slaves? Why are black people considered to be less human than white people?’ It takes these extraordinary moral artists that we called prophets to make us ask these dangerous questions that can maybe get us to move.”

At 91, Holloway’s movement has found limits. Walking has been a “lifelong compulsion”, a kind of sacrament. “Walking was its own meaning and purpose; it was the outward sign of an inner drive.” A dodgy knee and a minor stroke mean that he can no longer stride the heights.

“But now, I’ve got an exercise bike, because it’s weightless exercise. And opposite my bike in my bedroom there’s a lovely coloured photograph of my beloved Pentland Hills; so I’m on my exercise bike cycling through the Pentlands.”

To some people, that might sound a bit like heaven.

The Revd Malcolm Doney is a writer, broadcaster, and Anglican priest, who lives in Suffolk.

Last Words by Richard Holloway is published by Swift Press at £16.99 (Church Times Bookshop £15.29); 978-1-80075-533-8. See review here.

Listen to Richard Holloway in conversation with Malcolm Doney in this week’s Church Times podcast.