HAVING to go into a back room to view the works of Eric Gill is nothing new. At Gill’s first exhibition of sculpture in 1911, at the Chenil Gallery, Chelsea, visitors had to ask to view his erotic stone relief Votes for Women, exhibited separately from the main display, behind closed doors. Gill’s direct carved relief Ecstasy (1910-11), showing an entwined couple, modelled by his sister Gladys and husband Ernest Laughton, was also too explicit to be exhibited publicly. So, the decision by Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft to display Gill’s work in its own room, with a notice on the door, is in keeping with the artist’s complicated legacy.

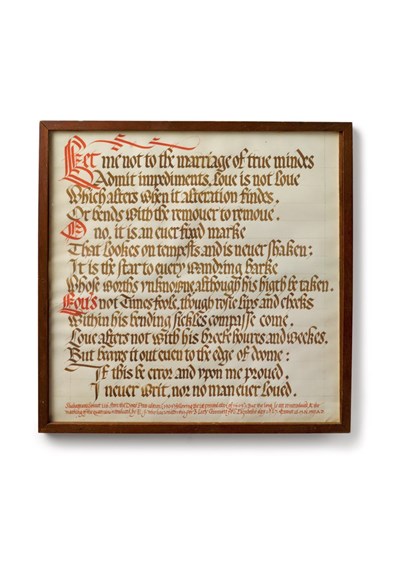

Collection: Ditchling Museum of Art + CraftEdward Johnston, Shakespeare’s Sonnet CXVI (1927) (used as book cover)

Collection: Ditchling Museum of Art + CraftEdward Johnston, Shakespeare’s Sonnet CXVI (1927) (used as book cover)

“It Takes a Village” is Ditchling Museum’s “living curatorial experiment” as it marks its 40th anniversary and prepares for a major redisplay planned for 2028. Displaying the work of 50 artists, the exhibition moves the spotlight away from Gill, putting in the foreground the artists and craftspeople who were associated with the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic. It also shows the continuity after Gill left the community in 1924 to move to Wales, three years after Gill founded the Guild.

The artist and poet David Jones visited Gill in Ditchling in 1921, recovering from the traumatic mental and physical health experiences of the First World War. Jones became a Roman Catholic the same year. His Our Lady of the Hills (c.1921) shows Mary tenderly kissing the Christ-child in her arms, the forms and shadows of their figures echoing the folds and curves of the South Downs in the background. The golden haloes of the Madonna and Child intersect, forming a diagonal figure 3 shape.

Jones’s celebrated 1938 inscription Dum Medium Silentium, taken from Wisdom 18.14-15, “For while all things were in quiet, silence, and that night was in the midst of her swift course . . .”, underlines the connection in his art between painting and writing.

Calligraphy was one of the wellsprings of Ditchling’s early-20th-century artistic community, as Gill had attended Edward Johnston’s classes in London before moving to Sussex. Johnson designed the London Underground roundel and its clear, modernist sans-serif typeface. His work inspired a generation of typographers, illuminators, and calligraphers. Moving to Ditchling in 1912, Johnston lived there for the rest of his life. But his friendship with Gill cooled when the artist became a Roman Catholic in 1913. Johnston was one of the few males in Gill’s circle who did not join the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic.

The part played by Ditchling as a centre of printing survived Gill’s exit from the Downs to found a new community at Capel-y-ffin. Hilary Pepler had met Gill in 1907 when he lived as Johnston’s neighbour in Hammersmith. Gill produced engravings for Pepler’s book The Devil’s Devices in 1915, and a year later Pepler established St Dominic’s Press in Ditchling.

For nearly two decades, St Dominic’s Press produced philosophical and religious material for the Guild, together with posters for local organisations, including the dramatic and horticultural societies. Pepler was voted out of the Guild in 1934 for introducing mechanised presses. He moved the press to Ditchling village from the Common, and renamed the workshop The Ditchling Press three years later. Brightly coloured posters for dances, exhibitions, and Ditchling Press itself are one of the highlights of “It Takes a Village”. The huge, black-metal, original Stanhope press that Pepler purchased, now 200 years old, still works, and it takes centre stage.

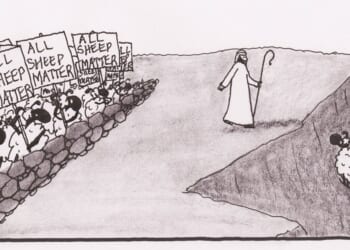

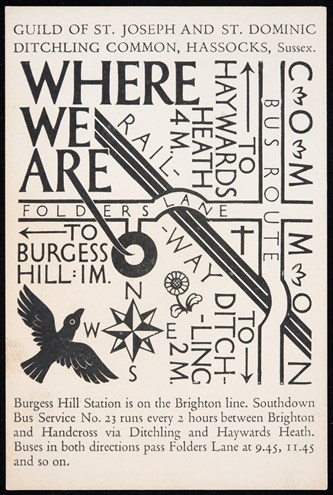

A promotional postcard for the Guild, We are Here (1933), fusing graphics and typography to point the way to Ditchling Common, showcases the work of Philip Hagreen. Hagreen’s anti-capitalist political cartoons for the magazine The Cross and the Plough reveal the Guild’s connection to Distributionism, a Catholic-leaning movement championing a more equal distribution of economic resources.

Textiles and weaving were also a well-established Ditchling craft. Ethel Mairet’s weaving and dyeing workshop, named Gospels, was established in 1918. Undated stoles by Valentine Kilbride, one of Mairet’s students, demonstrate the vivid orange, green, and red hues that natural dyes could achieve.

Collection: Ditchling Museum of Art + CraftPhilip Hagreen, Where We Are map

Collection: Ditchling Museum of Art + CraftPhilip Hagreen, Where We Are map

Petra Gill was also a student of Mairet, and her hand-woven wedding dress is outside the room of her father’s work, co-curated by the Methodist Survivors Advisory Group. The Group’s involvement springs from the Methodist Modern Art Collection’s unease over displaying Gill’s Annunciation (1912), part of the Collection.

The image of a rainbow-robed angel towering over a kneeling Mary was produced as a Mirrorscope slide, shown by Gill at social events for friends and family. Commentators from the MSAG have deemed Gill’s Annunciation oppressive of Mary, compared with accompanying depictions of the annunciation by Jones and Halgreen. Quite how the history-changing power of the annunciation can be conveyed without a sense of awe is not explained.

Much of “It Takes a Village” is laudable, especially showing the artistic array of beauty emanating from Ditchling, independent of Gill. And portraying Petra as a craftswoman and maker, and more than a footnote in her father’s corrupt story, is commendable. Yet, despite the partitioning off of Gill’s work and the excision of his Girl in Bath engravings from display, his presence in this show and in British 20th-century art is impossible to dispel. Gill’s potency as a contemporary bogeyman is proving as powerful as his reputation as one of the great artist-craftsmen of British art, if not more so.

“It Takes a Village” is at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, Lodge Hill Lane,

Ditchling, East Sussex, until 1 February. Phone 01273 844744. ditchlingmuseumartcraft.org.uk