AN IMPENETRABLE miasma of occultism hovers over exhibitions of artists active in the first half of the 20th century, especially women, and particularly British women. Interpretations of Ithell Colquhoun at Tate Britain echo Tate Modern’s show on Hilma af Klint, two years ago, in foregrounding the artist’s mysticism above all other influences.

Popular interest in the occult in the Victorian era and early 1900s is undeniable. More than 1200 publications on spiritualism and psychical research were published in America and England in the period 1891-1940, but mystical pursuits ran in tandem with established religious practice. Adolphus Woodford, one of the instigators of the occult Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, in the late 1880s, was Rector of Swillington, near Leeds, and a Masonic Grand Chaplain. Woodford was a vocal objector against the conviction of John Purchas by the clerical Court of Arches, in hearings ending in 1871, for overstepping the Ornaments Rubric in Purchas’s enthusiasm for birettas, copes, candles, and incense.

Colquhoun’s childhood was in the shadow of the Great War, and the understandable surge of interest in spiritualism and mysticism in the period 1916-20, triggered by the nationwide grief from the conflict’s death toll. Born in 1906, in the Indian hill station of Shillong, Colquhoun returned with her family to England the following year. She attended Cheltenham Ladies College, which offered girls “an education based upon religious principles”, embodied in the 1910 completion of the school’s new chapel.

At the Slade, Colquhoun was awarded joint first in the 1929 Summer Composition for her oil painting Judith Showing the Head of Holofernes. The Slade’s emphasis on the study of historical painting, and support for mural painting can be seen in the flatness of the figures and schematic composition. Judith’s triumphant, red-clad figure suggests a triangle, with the Assyrian general’s head, held by the tip of a quiff, at its apex. Two parallel rivulets of blood falling from Holofernes’s severed neck to the ground underline a sense of perpendicular space. Judith’s muscled, thrusting arm points towards the artist’s interest in androgyny.

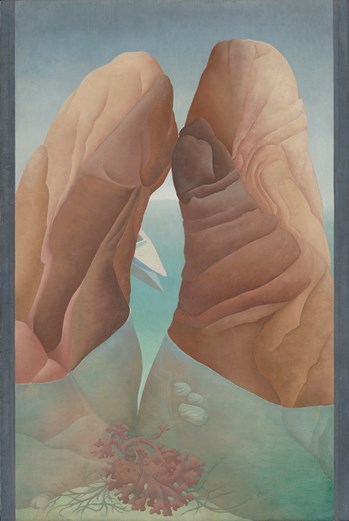

© Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © SamaritansIthell Colquhoun, Scylla (méditerranée) (1938). Tate: purchased 1977

© Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © SamaritansIthell Colquhoun, Scylla (méditerranée) (1938). Tate: purchased 1977

In the early 1930s, Colquhoun painted three more works on biblical and Christian subjects: Death of the Virgin (1931), Aaron Meeting Moses (1932), and Song of Songs (1933). Stylistically, Death of the Virgin looks forward and back. It is resonant of Edvard Munch’s portrayal of his sister Sophie’s death in his Deathbed and Sickroom series of works in the early 1890s, showing a central figure in bed, surrounded by the awestruck and prayerful.

Colquhoun’s work’s decorative frame within a frame references the architectural features found in Renaissance religious paintings, in which arches and doorways both emphasised the boundary between the painting and the outside world, but also symbolically invited the viewer to enter sacred space. Metaphorical representations of the Virgin as the gateway to heaven, the porta coeli, add another layer of engagement with Christian artistic traditions. The detailed modelling of the figure of Mary’s limbs beneath the blankets and dark pink background surrounding the crucifix above the bed add Colquhoun’s individual take on the scene.

In Song of Songs, the muscular two figures reflect both the artist’s interest in androgyny, but also the post-First World War trend in British art for a “return to order”, with neo-classical figures and naturalism, replacing the turn-of-the-century interest in experimentation with form and abstraction.

Throughout the 1930s, Colquhoun deepened her relationship with surrealism. Having briefly lived in Paris in 1931, she visited the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936, where Salvador Dalí gave a lecture dressed in a diving suit. But her membership of the Surrealist Group in England was curtailed by the group’s leader E. L. T. Mesens, who forbade members from joining other societies, including occult orders. Having joined in 1939, Colquhoun left the following year.

The artist engaged with the Theosophical Society, aiming for a fusion of religious teaching, and followed the teachings and rituals of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which, despite no credible documentary evidence, traced its teachings’ origins back to ancient Egypt.

Occultism’s appeal as a possible answer to the existential questions of the inter-war period can be seen in W. B. Yeats’s support for the Golden Dawn, and Arthur Conan Doyle’s promotion of spiritualism. In the dark days of 1941, Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit, a comedy about a medium “bringing back” a newly married widower’s dead first wife, opened at the Piccadilly Theatre. Coward’s inspiration came from the novelist Radclyffe Hall’s engagement of a medium, after a lover in her ménage à trois died, underlining the appeal of occultism’s inclusive attitudes to same-sex relationships. Occultism and spiritualism also elevated women to high-priestess roles of spiritual authority, unthinkable at the time in mainstream religion. Embracing occultism could have been more a critique of conservative Christian institutions than of Christian teaching.

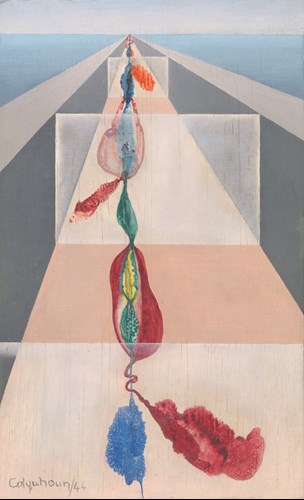

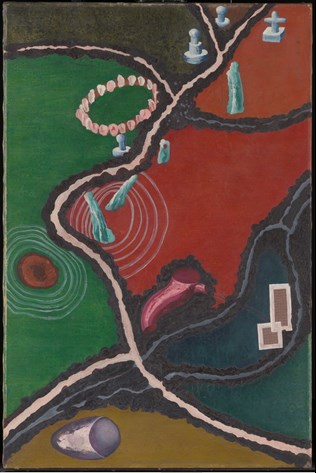

© Tate. Photo © Tate (Joe Humphrys)Ithell Colquhoun, Ages of Man (1944). Presented to the Tate by the National Trust in 2016, accessioned 2022

© Tate. Photo © Tate (Joe Humphrys)Ithell Colquhoun, Ages of Man (1944). Presented to the Tate by the National Trust in 2016, accessioned 2022

Colquhoun’s most celebrated work, Scylla (1938), can be read as an eroticised seascape or a briny depiction of a female lower torso and thighs. The artist embraced Dalí’s notion of the “double image”, creating works that simultaneously spoke of female emancipation and men’s emasculation. The artist said that Scylla’s imagery came from “a dream-like state” rather than a dream, and this distinction sheds useful light on the various occultists’ accounts of astral planes and meeting Isis, as it shows an awareness of fantasy co-existing in the day-to-day.

Rivières Tièdes (méditerranée) and Gouffres Amers (méditerranée) (both 1939) employ Christian associations to express ideas on alchemy and death. In Rivières Tièdes (on the theme of fading love), interlocking rivulets of blue, white, red, and yellow flow down the steps of a church modelled on one Colquhoun had seen in Corsica. Blue and white are associated with the feminine in alchemy, while red and yellow, the colours of elemental fire and philosophic sulphur (type of sulphur identifiable by alchemists), are masculine. Gouffres Amers, meaning bitter abyss or chasms, depicts a reclining skeletal figure of death. A sea anemone performs the modesty task of a fig leaf.

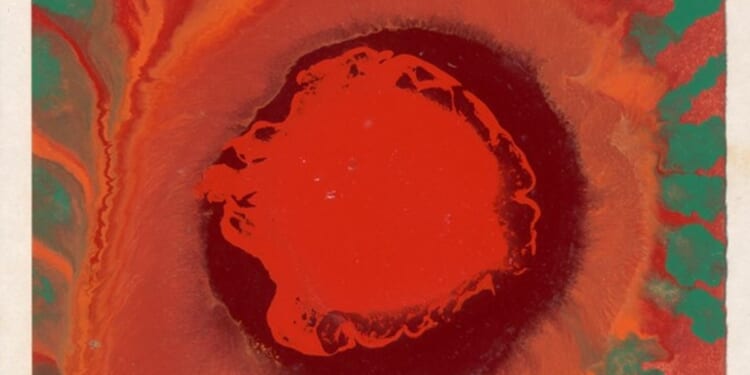

In 1949, Colquhoun published The Mantic Stain. “Mantic” means prophecy and “stain” refers to images that she made through decalcomania a process of applying paint to a surface, then pressing another surface against it. The artist compared automatism — making art without conscious thought — to divination, an awareness of future events beyond human senses.

Works from this period include Guardian Angel (1947) and Gorgon, from a year earlier. Gorgon was originally going to depict a guardian angel, but the horned shapes from the automatism were “so horrific that I had to call it a Gorgon instead.” In an earlier work, Second Adam (1942), the figure stands in a yoga tree pose, with internal organs diagrammatically rendered, against a background of concentric orange, yellow, and brown. The mystic Claude Bragdon’s proposed fourth dimension, where both the body’s internal structure and its spiritual aura would be visible, is suggested in Second Adam.

The artist moved permanently to Lamorna in 1959, having divided her time between London and Cornwall for the previous two decades. She joined the Order of Druids, an Anglophone friendly society, symbolised by a poet with a harp, and the Ancient Celtic Church, dedicated to the spirit of British Christianity pre-Augustine’s mission. Colquhoun wrote of the Cornish landscape as inscribed with sacred rituals and ancient spiritual traditions. Published in 1957, her exploration of Cornwall’s early monuments and folk traditions, The Living Stones, employs the metaphor for priesthood in Peter and Ephesians.

© TateIthell Colquhoun, Landscape with Antiquities (Lamorna) (1950). Presented to the Tate by the National Trust in 2016

© TateIthell Colquhoun, Landscape with Antiquities (Lamorna) (1950). Presented to the Tate by the National Trust in 2016

Works inspired by Cornwall and exploration of Celtic culture include La Cathédrale Engloutie (1950), in which an islet in Brittany stands for the shifting boundary between land and sea. St Elmo (1947), is named after one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers and patron saint of sailors. Santa Warna’s Wishing Well, from the same year, shows a vegetal figure, on top of a green hill, with a cut-through section of a cavern and green steps beneath. The saint was adopted as the patron saint of ship-wreckers, with the custom of throwing bent pins into the well. St Warna’s Well in St Agnes, in the Isles of Scilly, remains an active place of pilgrimage today.

Undated works on paper from this period include Sketch of a Cubic Calvary Cross and Sketch Showing the Ten Divisions of the Body of God.

Colquhoun died in 1988. In 2019, most of the artist’s work and archive material was transferred to the Tate, forming in the gallery’s words, “the world’s largest collection of the mystic artist, writer and occultist”.

But do occultism’s turn-of-the-century top-drawer and famous adherents, lending an air of social proof, and its theatrical appeal to wider audiences, amount to a defining influence on 20th-century art? A contemporary comparison is conspiracy theories and anti-vaxxing, which gain traction in some communities, then receive a wider hearing, but rarely gain mainstream acceptance.

Faint traces of Christianity in current curatorial trends do not equate to absence of Christianity in the art or the artist.

“Ithell Colquhoun” is at Tate Britain, Millbank, London SW1, until 19 October. Phone 020 7887 8888. www.tate.org.uk