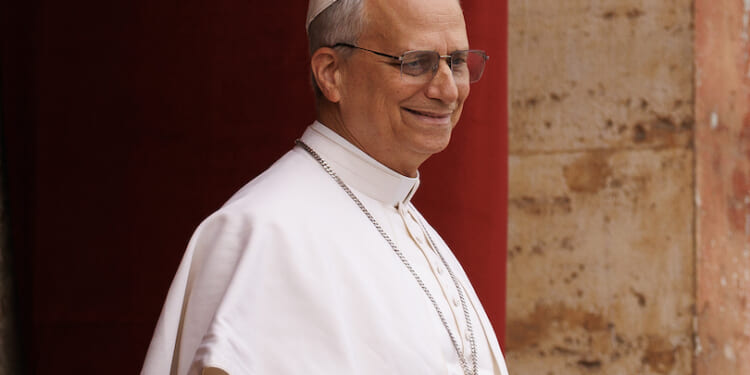

(LifeSiteNews) — Leo XIV has explicitly positioned his new exhortation Dilexi Te in continuity with his “beloved predecessor” Francis, echoing many of the same themes pertaining to migrants and calling for “a world and a Church without barriers.”

The exhortation, Leo says, was originally written by Francis as a continuation of his encyclical Dilexit Nos, with Leo “adding some reflections” and thereby making it “his own.” Of the 130 footnotes, more than 50 refer to his predecessor’s texts and addresses.

Yet while Dilexi Te makes a number of pointed criticisms of greed, “trickle-down” economics, and a “faith without works” religion, its treatment of migration neglects essential distinctions long recognized in Catholic tradition.

The section “Accompanying Migrants” (nn. 73-5) grounds itself in biblical imagery: Abraham setting out from Ur, Moses leading Israel through the desert, the Holy Family fleeing into Egypt. From these precedents, Leo concludes that “the experience of migration accompanies the history of the People of God,” and that migrants embody “a living presence of the Lord.”

READ: Pope Leo XIV continues Francis’ emphasis on a ‘poor Church for the poor’ in new exhortation

Leo points to the care of European migrants in the United States, and the example of Bishop John Baptist Scalabrini and St. Frances Xavier Cabrini – whom Pope Pius XII made patroness of migrants in 1950. He also refers to Francis’ comment on Scalabrini in the canonization sermon: “Scalabrini looked forward to a world and a Church without barriers, where no one was a foreigner.”

He specifically praised refugee “reception centers, border missions and the efforts of Caritas Internationalis and other institutions” – and repeated Francis’ “response” to the contemporary migration crisis as “welcome, protect, promote and integrate.”

“Migrants and refugees do not only represent a problem to be solved,” he added, again citing Francis. “In every rejected migrant, it is Christ himself who knocks at the door of the community.”

Again citing Francis, he extended these ideas to “all those living in the existential peripheries.” The Church, the document continues, “builds bridges where walls are built,” and proves her credibility by “gestures of closeness and welcome.”

What the Church teaches about immigration

The Church upholds a qualified, rather than absolute, right to migrate – one limited by the common good, the nation’s capacity, and the duty of rulers to safeguard their own citizens. Pius XII bound the right of movement to “public wealth, considered very carefully.”

St. Thomas Aquinas likewise taught that while rulers must care for “strangers,” their immediate admission to full civic participation could endanger the common good and the faith.

Leo XIV’s language makes no reference to these limits, or to the social upheaval caused to host nations by contemporary mass migration – nor to the growing injustice in the indulgence shown to economic migrants, at the expense of citizens.

The absence recalls recent controversy over U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance’s reference to the ordo amoris – the “order of love” by which justice binds one first to family and nation before extending care to others.

While this order may be suspended in the face of immediate distress (as with the Good Samaritan), St. Paul clearly taught:

But if any man have not care of his own and especially of those of his house, he hath denied the faith and is worse than an infidel.

READ: Pope Leo’s scandalous abortion remarks could help Democrats: here’s how

St. Thomas Aquinas, who also states that it is wrong to give alms from what is strictly necessary for the support of our dependents, comments on this passage:

And, as Augustine says, we can wish well to everyone, but those who are closer to us are regarded as our principles [sic] and, consequently, more worthy of love. Ambrose says that the reason for this is that perhaps those who are not ashamed to receive from their own would be ashamed to receive from others.

He has denied the faith by his works, because if he does not observe the faith in regard to those to whom nature has joined him, the result is that he will not observe it in regard to others: they profess that they know God, but in their works they deny him (Titus 1:16).

At the time of Vance’s comments, Francis dismissed the ordo amoris, saying that “Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups.” Prior to the May conclave, the then-Cardinal Robert Prevost also shared an article from NCR Online which denied this, with the headline: “JD Vance is wrong: Jesus doesn’t ask us to rank our love for others.”

New Pope Leo XIV, formerly Robert Prevost, tweeted at the VP earlier this spring, quoting an NCR Online piece that is headlined: “JD Vance is wrong: Jesus doesn’t ask us to rank our love for others.” pic.twitter.com/MLZZ2kRNAI

— Mary Margaret Olohan (@MaryMargOlohan) May 8, 2025

Leo’s call for universal “integration” overlooks the civil ruler’s primary duty to preserve the stability, culture, and faith of his own people. It therefore fails to speak to current Western migration crises, which are widely felt to be defined by the neglect of that duty.

The result is an appeal that reads less like the social realism of Scripture and Tradition and more like the borderless idealism of modern left-wing ideologies: a moral vision which sounds generous in the abstract, but is detached from the concrete justice owed to nations and families.